Nineteen fifty-nine was a pivotal year in jazz. In August, trumpeter Miles Davis released his landmark album Kind of Blue, which would go on to become the best-selling jazz record of all time thanks to its accessible blend of blues and modal voicings. But in November, self-taught tenor saxophonist Ornette Coleman blew Davis’s mainstream style wide open during a two-week residency at New York’s Five Spot Cafe. Coleman and his quartet premiered an entirely different, avant-garde sound that was lauded by critics but deeply controversial among audiences. Disregarding conventional chord structures in favour of an anarchic, unpredictable and often atonal improvisation, he birthed a new concept: free jazz.

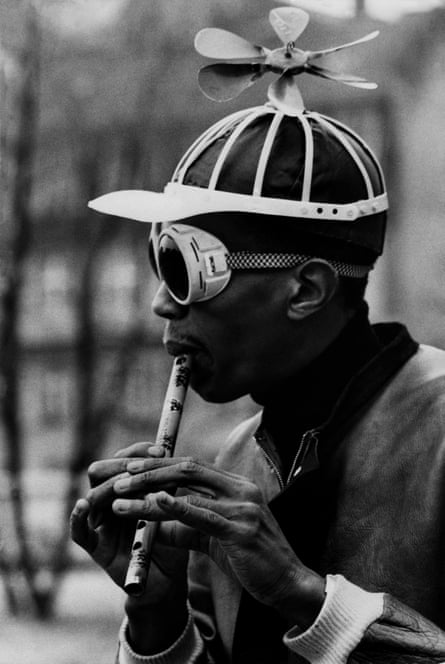

Flanking Coleman on stage was 23-year-old Oklahoman trumpeter Don Cherry. Blending the saxophonist’s melodies and frenetic lines with his own self-assured, bright phrasings, Cherry was Coleman’s harmonic partner amid the cacophony. Using a compact pocket trumpet with a bell that sat closer to his mouth, as if he was singing when he played, he was the open ear capable of turning a monologue without form into a dialogue of its own.

In the years following that infamous Five Spot residency, Cherry would go on to develop his own theory of “collage music”, applying the freeform methodology he honed with Coleman to incorporate new influences. An early pioneer of what we might now call “fusion” or global music, Cherry formed several genre-spanning bands absorbing non-western musical traditions from his travels to Morocco, India and South Africa. He crafted a signature sound that contained fragility within its breathy power, teetering on the edge of dissonance. It could be heard on ensuing collaborations with everyone from director Alejandro Jodorowsky to pianist Carla Bley, Ian Dury, saxophonist Sonny Rollins, and his stepdaughter, singer Neneh Cherry.

“In my view, there are three great trumpet and saxophone pairings in jazz history,” percussionist Kahil El’Zabar says. “Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker, who invented bebop; Miles Davis and John Coltrane, who evolved harmonic complexity and melodic agility; and then Ornette and Don, who created cacophony without hierarchy. For Don to keep up with Ornette made him one of the baddest technicians to ever play the instrument.”

Twenty-seven years on from Cherry’s death, El’Zabar is now performing a tribute concert to his music as part of the London jazz festival. He first met Cherry in 1974, as a 25-year-old playing his first shows in Paris. The pair went on to share multiple lineups and become lifelong friends. “I’m always influenced by Don, since he showed me how to emulate the human spirit through sound – he was always trying to ascend to something greater than just the notes,” El’Zabar says. “He was a genuine visionary and we have to celebrate what he has taught us all.”

El’Zabar recounts one memorable teaching moment from Cherry in the 1980s while he was supporting Cherry’s Old and New Dreams group in Switzerland. “I wanted to play my ass off to impress Don, so I made sure that our set got really intense,” he says. “Don then walked on and winked at me. After we had played with such velocity, he started at a whisper and took the audience back to a place of real sensitivity. He was a master of dynamics and showed me that you can still have an intensity of feeling through focus, rather than just playing hard and fast.”

Throughout Cherry’s life, teaching his methods became an important part of his practice. Most notably, for a decade from the late 60s, Cherry relocated from New York to the municipality of Tågarp in Sweden with his wife, the visual artist Moki Cherry, to establish a music workshop from an abandoned schoolhouse. Living, teaching and hosting visiting musicians such as Turkish drummer Okay Temiz and Brazilian multi-instrumentalist Naná Vasconcelos from the same space, Don and Moki removed themselves from the commercial pressures of the live touring circuit and instead incorporated their family life into a new commune of artistic practices.

In 1974, Cherry’s 16-year-old son David Ornette Cherry made the journey from Los Angeles to Tågarp. “Don was my first teacher and it was all about doing with him,” David says. “After only a month of sitting next to him on the piano bench and learning by watching him play, he took me to a smoky club to perform. He was at the edge of the stage, blowing a deep sound from a big blue horn. I ran over and asked, ‘when are we starting?’ He looked at me, smiled and took it out of his mouth to say, ‘it’s already started’.”

Now an award-winning jazz pianist, David is speaking over a video call from the same Tågarp schoolhouse that has since become the Cherry family headquarters. He is flanked on one side by the upright piano he was taught on, painted in vibrant colours by Moki, and on the other side by his niece Naima Karlsson. “Every memory I have of Don is him playing an instrument or teaching us songs,” Karlsson smiles. “He could make an instrument out of anything and he made us all excellent listeners, since he was a very open musician who always wanted to learn himself. He was someone who was able to experience the music as being alive and that is what carries on in the family today.”

As well as featuring El’Zabar’s Ethnic Heritage Ensemble, the London jazz festival concert is a Cherry family affair, including Karlsson’s sister, the singer Tyson, as well as David on piano. Karlsson herself will be performing an improvised piano duet with one of her grandfather’s collaborators, pianist Ana Ruiz.

In 1977, Cherry and Moki spent seven months in Mexico City with Ruiz on a government grant to teach their free jazz-influenced workshops. Everyone from local musicians to actors, artists and even children would stop by to watch Cherry play the pocket trumpet or African hunter’s harp while Moki emblazoned tapestries with motifs for his performances. Cherry encouraged his students to listen for “ghost sounds” – the unexpected rhythmic or harmonic resonances in their playing – and to embrace them as part of the spontaneous control of their improvisation. “We would play for four hours in the morning and then in the evening we would continue at home,” Ruiz laughs. “We were like a family and Don would always be making songs – one or two each day, which he would just sing to us and then we would keep repeating it until it was memorised and ready to play the next day. Nothing was written down – it was an entirely new way of learning.”

Ruiz explains how free jazz wasn’t accepted by the genre traditionalists in Mexico at the time but the popularity of Cherry’s workshops established a new appetite for the music across the country. “We opened up the listeners and musicians to other, less predictable experiences,” she says. “Don would always say, ‘let’s play and the people will find us’. We never played a melody the same way twice – it’s something that has changed my life.”

For El’Zabar, that restless pursuit of the new is what makes Cherry’s legacy one that will not be fully appreciated for decades to come. “The geniuses thought he was a genius – people like Sonny Rollins, Pharoah Sanders, Albert Ayler, Ornette Coleman, they all wanted to play with him,” he says. “His voice is more relevant today than in his lifetime, and it will become even more relevant as time goes on.”

Ultimately, his family have made it their work to unpack the Cherry legacy and Karlsson has spent recent years organising Don and Moki’s extensive archive, featuring it in a 2021 book, Organic Music Societies, as well as developing a forthcoming documentary. She sees the London concert as just another element in their expansion of Cherry’s creative practice. “We just want to continue Don and Moki’s process of giving audiences something that inspires them in their life,” she smiles. “Perhaps it might help them to hear and see the world a little differently, which Don did for so many others while he was alive.”