For 17 years have I carried this, the heaviest of burdens: knowing that everyone was wrong about a movie. I shouldered this hardship as nobly as I could, knowing that there are people in the world who have it much harder than I (Stargate fans, probably) but injustice must be answered, not with silence, but with truth. And here it is: For almost 20 years, everyone has been wrong about Spider-Man 3.

Polygon’s Spicy Takes Week is our chance to spotlight fun arguments that bring a little extra heat to the table.

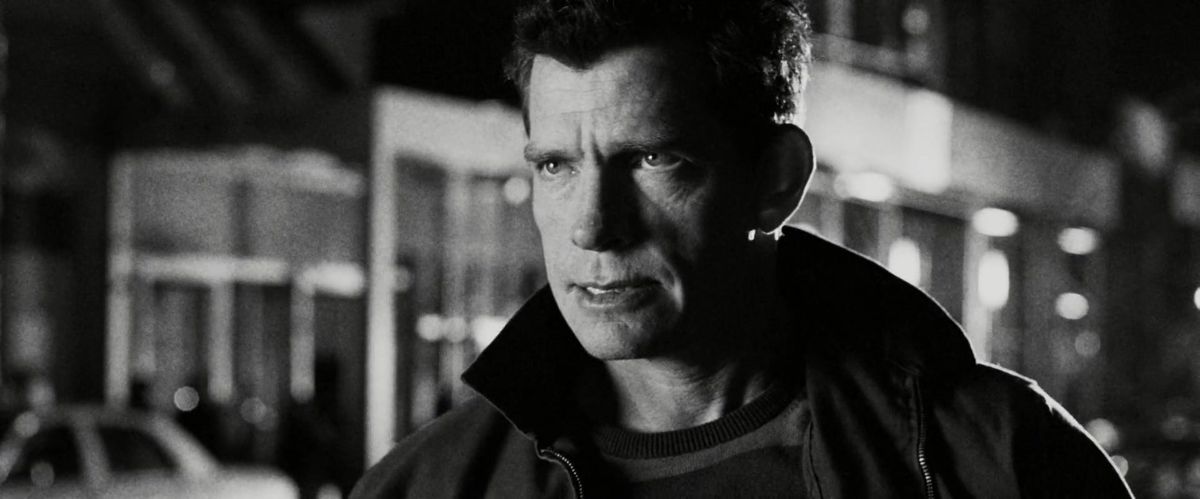

Sam Raimi’s 2007 sequel to the best superhero movie ever made has been on an interesting journey through the years. The film was immediately seen as the lesser entry in Raimi’s pretty spectacular trilogy, and that’s still a fair assessment. (Again: Spider-Man 2 is the best.) But more recently, its reputation has grown, as fans’ knee-jerk dislike of the film’s goofball sensibilities and uncool take on a dark Peter Parker leveled out into an appreciation for what Raimi was doing, and the big-hearted sweetness of his version of the character.

This is a good thing. There is a lot to love about Spider-Man 3, and Tobey Maguire’s dancing was never the problem a million late-2000s memes made it out to be. The real problem was much bigger, and far less superficial: It made Uncle Ben’s death not Peter Parker’s fault.

Spider-Man 3 kicks off its entire emotional arc with a retcon, as Peter learns new villain Flint Marko/The Sandman is in fact his uncle’s real killer, and the thief from the first film merely his accomplice. This revelation sends Peter in a rage spiral that makes him susceptible to the alien costume that attempts to bond with him, and causes him to nearly destroy all of his personal relationships.

Images: Sony Pictures

I understand how a storyteller would get here, and why they would want to do this. I just happen to think it is a disastrous choice for a story about basically any version of Peter Parker. More than the spider bite, more than the costume, more than “with great power there must also come great responsibility,” the fundamental truth about Peter Parker is that he never gets over it. He blames himself for what happened to Uncle Ben, and the terrible thing is he’s right. He could have done something, and so he vows to never stand aside and do nothing again.

People often say that Spider-Man is popular because he’s relatable, working class, or that he’s got a full-body costume and, in the lily-white world of ‘60s comics, you could imagine yourself under that mask. That’s all important, definitely, but I think the real reason is guilt. Spider-Man’s staying power comes from the self-loathing baked into his origin, the difference between a teen coming of age story that rings true and one that does not.

You’ll notice a funny thing about Peter if you ever revisit those old Steve Ditko/Stan Lee comics: he’s a little prick. He’s mad at the world for ostracizing him as a nerd, drunk off his newfound powers even after the terrible accident that compels him to become Spider-Man. Were his story told today, he’d certainly find his way to certain online communities that would indulge in his worst impulses and cause his malcontent to fester into something truly toxic.

This is also true of ‘60s Peter, but something terrible happens, and it’s all his fault. There is no way to shift the blame, he must simply deal with it. And he does. Every damn day of his life, from then on.

The beauty of those comics is that, eventually, the petulance starts to bleed away. He dresses up in a ridiculous costume and pretends to be a better person than he feels he is, and it starts to rub off. He becomes that better person.

Image: Sony Pictures/Everett Collection

The reality of comic book superheroes is that they are meant to be static. The more compelling they are suspended in an endless second act, the more successful they will be. Films however, end, and adapting superheroes to their structure can result in compelling new reads on a character once they are allowed to have an ending. Spider-Man 3 doesn’t quite give Peter Parker an ending, but it does close the book on his coming of age: Across three films, Peter graduates from high school, goes to college, begins a career, finds love, and nearly loses it all in an all-consuming fit of selfishness — from which he must rebuild his life with humility, and hope the people he cares about will still have him. It’s a beautiful arc, but it doesn’t engage with who Peter is without that guilt, and what drives him now instead. (Perhaps the hypothetical Spider-Man 4 would have addressed this, perhaps it has not happened because doing so would return to a story that is over.)

That’s a question that shouldn’t go unresolved. The Neverland of comic book superheroes and corporate IP dictate that characters grow or change glacially, if it all, and eventually everyone has their fill and outgrows them. Spider-Man lingers, though, perhaps because he is the rare character better in suspension. And even though it flies in the face of this in one critical way, Spider-Man 3 still acknowledges this in its ending, as Peter and MJ dance on the precipice of forgiveness in the face of an uncertain future. They’re not kids anymore, but their adult lives are theirs to own. Will there still be a Spider-Man? Who knows? Here is where we exit.

A well-adjusted adult would just forgive themselves and move on, but Spider-Man isn’t a story about becoming a well-adjusted adult. It’s about looking your worst day in the face, when you’re the worst version of yourself, and doing something about it. About refusing to wallow in the world’s unfairness, and putting something better out into it, simply because you can. And that kind of work never ends. It’s an aspiration. Every day Peter Parker does it, he really is The Amazing Spider-Man.