Steven Spielberg has been known to explore science fiction in many of his films, like Minority Report, E.T. The Extraterrestrial and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. But his company Amblin rockets into science fact with Good Night Oppy, a documentary about NASA’s 2003 mission to send rovers to Mars to look for signs that water once flowed on the Red Planet.

Amblin approached Ryan White to direct the film, a wise choice given not only his skill as a director but his affection for the subject matter.

“I’m a space geek,” White tells Deadline. “So, I had followed these missions myself.”

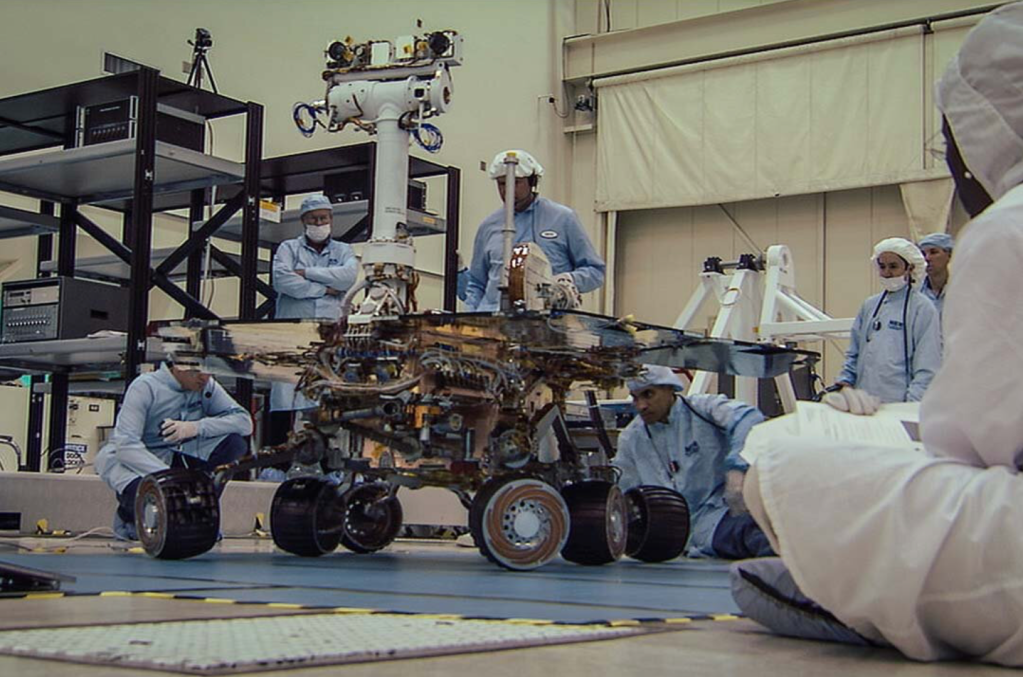

NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory launched two rovers to Mars within weeks of each other — first Spirit and then Opportunity (the “Oppy” of the title). White documents the maniacally tight deadline faced by engineers designing the rovers; they needed to get the vehicles ready to go for the moment when the orbits of Earth and Mars aligned most closely, otherwise the mission would have to wait another two years for the next window of Opportunity (so to speak).

From the get go, engineers and scientists involved in the mission imbued the rovers with human characteristics – in some ways consciously, in other ways unconsciously. They deliberately designed Spirit and Oppy — the nickname NASA gave Opportunity — to be 5’2” tall (“the average height of a human” as one NASA expert points out). The cameras on the vehicles peered out like eyes from beneath a brow-like metal protrusion.

The men and women who participated in the mission told White they developed feelings for their robotic creations early on. They referred to them by the female gender.

“I would think that NASA scientists and engineers would be relatively unemotional and be very practical thinkers and detached from their work,” White admits thinking. But it didn’t turn out that way. “They project their own hopes and fears onto these rovers.”

Steve Squyres, the scientist responsible for overseeing the Mars research, told White that as the launch neared he felt like he was seeing his kids grow up and go out into the world on their own.

“Time and time again, we saw how much more than just a job this was to people,” the director says, “that it was this incredible emotional bond.”

Good Night Oppy, from Amazon Studios, opened in theaters last Friday, and premieres globally on Amazon Prime on November 23. The film has earned six Critics’ Choice Documentary Awards nominations including Best Documentary Feature, Best Director and Best Science/Nature Documentary and also won the Truly Moving Picture Award at the Heartland Film Festival in Indianapolis.

Amazon Studios

One of the singular achievements of the film is giving us the sense we are watching Spirit and Oppy on Mars as they undertake their perilous mission of scientific discovery (it’s a remarkable illusion because, in reality, the nine cameras on board each rover pointed outward, so there was no video “looking” at them). The impression is created through visual effects that put us on the surface and above the terrain of the planet.

“I said to Amblin… ‘Can we take the audience to Mars in a way that’s never been done, but do it in a documentary way?’” White recalls asking. “’Let’s not do it the way it’s typically done, which is an actor on a desert, shooting scenes, and then visual effects are created around them… Can we build it from the ground up?’ And they said, ‘Let’s talk to Industrial Light & Magic.’”

That would be the special effects company founded by George Lucas.

Deadline

“[ILM] admitted they had never done that before,” White says. “It was a real leap of faith that we were taking together, myself as the director, trusting that they would deliver on this idea that it could be completely authentic and look photo-real. I kept saying, ‘I do not want to make a cartoon. So, if it’s going to look like a cartoon, we should not start this.’ And they said, ‘We can pull this off.’”

While ILM worked on its end, White conceived the camera moves that would be executed once ILM’s motion graphics were all set.

“I worked with an incredible storyboard artist named Josh Sheppard for months, and we, frame by frame, drew out the film,” White explains. “It was like a comic book for a long time, like it would cut between interviews and then these pencil sketches. Once ILM came on board, they definitely helped us rework some of those scenes. But the film is pretty faithful to all of those original storyboards, and that was a really fun, creative, experimental process with Josh.”

Spirit and Oppy were only meant to last 90 “solar days” on Mars. Incredibly, they vastly exceeded expectations, weathering brutal Martian winters, lashing dust storms and geological minefields that threatened to obliterate them or mire them in something akin to quicksand.

Spirit gave up the ghost, as it were, after all most seven years of active exploration. Oppy held on even longer – for 14 years. The “deaths” of these rovers hit the mission engineers and scientists like a deep personal loss, a feeling many viewers of the documentary may share. Anthropomorphizing seems to be a human impulse, yet it’s also in NASA’s interest to design “creatures” that deliberately tug at our heartstrings.

“They are very conscious that this is our mission too, that we are the taxpayers paying for these missions,” White notes, “and they want us to come along for the journey.”