In 1993, my parents saved up enough money to buy a massive Kenwood home entertainment system complete with gigantic speakers and a five-CD player.

I remember the exact year because the first CD I ever bought was “Promises and Lies” by UB40 — don’t judge.

My second CD was “Art Laboe’s Memories of El Monte: The Roots of L.A.’s Rock And Roll.” That one quickly became scratched and scuffed because of how much I played the collection of oldies but goodies mixed in with 1970s R&B stars like Earth, Wind & Fire and the Intruders.

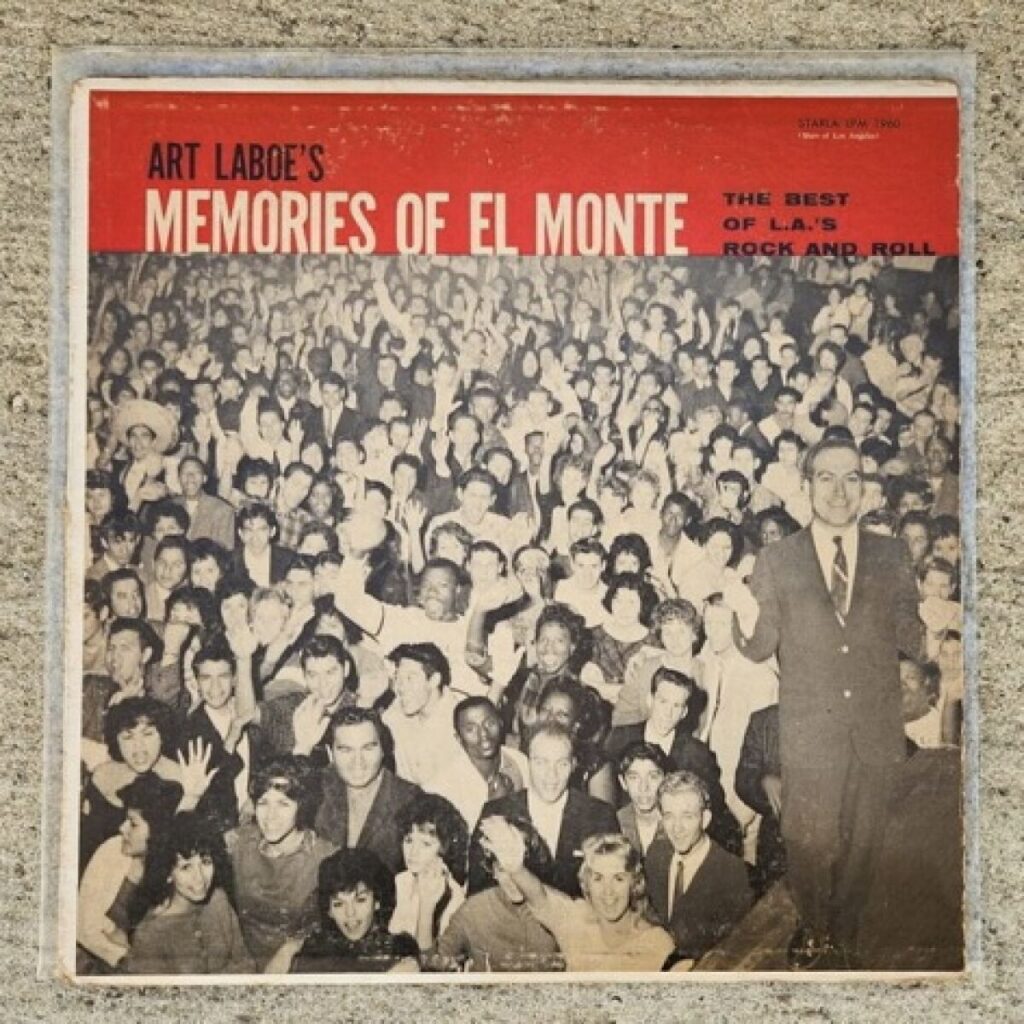

As the songs played again and again on the Kenwood or the knockoff Walkman my parents eventually bought me, I’d stare at the “Memories of El Monte” cover.

It’s a photo of one of the many dances and concerts Laboe, a pioneering DJ who died last week at age 97, hosted at the old El Monte Legion Stadium during the 1950s, when he essentially introduced rock ’n’ roll to the Southland.

The original album cover for “Art Laboe’s Memories of El Monte,” which was re-released as a CD in the early 1990s with a different photo of Laboe but the crowd shot left intact.

(Gustavo Arellano / Los Angeles Times)

A young Laboe is near the edge of the cover, on stage and holding a mic, a pose slightly different from the original album. Even though his name is on the album, Laboe isn’t the focus of the photo. That would be the packed, joyous crowd.

I’d stare at it again and again because it was a scene I didn’t recognize in my super-Mexican neighborhood or high school. It was diverse.

A white girl near the bottom corner waves at the camera. A Black couple hold something in their hands. A young Asian American man grins. A Latino teen wears what looks like a tuxedo jacket and a massive sombrero.

“White kids from Beverly Hills, Black kids from Compton and local Chicano kids used to come out to our shows every weekend,” Laboe told an academic decades later — a rarity then, and even rarer today.

The tracks on “Memories of El Monte” were meant to evoke the raucous spirit of those shows. Tejanos belt organ-drenched love songs in Spanish. Black artists blaze through “Pachuko Hop”

and “Corrido Rock.” There’s even a doo-wop song penned by freak-rock icon Frank Zappa.

I’m streaming that album right now on YouTube, not just because of Laboe’s death but as an incantation against the noxious vibe that emanated this week from L.A. City Hall.

A year-old recording recently emerged that features L.A. Councilmembers Nury Martinez, Kevin de León, Gil Cedillo, as well as then-Los Angeles County Federation of Labor President Ron Herrera, using racist, classist and misogynistic language against their political rivals and even a Black child. The fallout from their crass comments has upended L.A. politics and will cast a shadow of skepticism over Latino political power for years to come.

Multiple communities are looking for healing right now. Everyone is looking for someone to bring us together, to take us to that promised land of integration and allyship that always seems to be just out of grasp in Los Angeles.

We had that person. His name was Art Laboe.

The obituaries are rightly hailing his genius — how Laboe played rock ’n’ roll in Southern California when L.A. radio was still mostly country, Perry Como and farm reports. How he trademarked the term “oldies but goodies” as far back as the early 1960s. How he built a musical empire on nostalgia via sold-out concerts and especially his call-in show.

It was the stuff of fascination for academics and hipsters alike: How did this old white man with a buttery voice get an army of sad girls and smileys from Victorville to pour out their hearts every night with on-air dedications to loved ones?

Laboe wasn’t trying to keep alive a peaceful past where no problems existed. His mix of yesteryear and today was an eternal act of rebellion. Every song, every dance, every fan was a quiet attack against racism, in a decades-long career that started at a time when schools and housing were legally segregated, and concluded in a present where such discrimination sadly still exists.

Racism couldn’t get past the bouncer in the Laboe universe. At shows he hosted, rock legend Jerry Lee Lewis played one night, soul sensation Jackie Wilson performed on another. There was so much dancing and friendly interaction between racial and ethnic groups that El Monte authorities fretted about what chaos the shows might provoke (hint: nothing) and ultimately tore down Legion Stadium to build a post office.

“If this great stadium was still here today,” the liner notes for “Memories of El Monte” read, right above a photo of the long-gone structure, “we would still be having our dances and good times.”

His radio program, “The Art Laboe Connection,” weaved its way through decades of musical styles — Chicano rock group Tierra, Motown B-sides, the multicultural Tower of Power, even hip-hop — within the span of half an hour.

I loved Laboe’s shows, not just because the music was great, but because they taught me about people who weren’t like me. While other L.A. stations played the tried-and-true, like the Beach Boys or the Beatles, he preferred artists like Brenton Wood, a Black singer from Compton who had a decades-long career largely supported by Latino fans like myself. Long before there were talks about prison reform, Laboe urged compassion for incarcerated people — it took me years to realize that the reason so many dedications came from Chino was because of the state prisons located there.

There’s an unlikely Laboe connection to the L.A. City Hall scandal. At one point on the recording, the conversation turned to Armenian American Councilmember Paul Krekorian and his former chief of staff, who is also Armenian. Martinez couldn’t remember the staffer’s name, but described him as “the guy with one eyebrow.” Cedillo responded, “I bet it ends in i-a-n,” referring to the traditional patronymic in Armenian surnames.

Laboe was Armenian himself, born Art Egnoian. Cedillo was a huge Laboe fan, telling The Times in 2009 how he and former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa used to cruise in the 1970s with Laboe’s show on the radio. “There was no place else to be,” Cedillo said, “but right there, listening to his music.”

He wasn’t listening closely enough.

I met Laboe only once — sometime in the mid-2000s, at a rooftop party after an L.A. Weekly music awards show in Hollywood. He was short — just over 5 feet — yet held court with the Black and Latino young men and women who flocked to the then-octogenarian to say how much he meant to them.

No one asked for autographs — Laboe freely handed out business cards with his signature on one side.

On the other side was a photo of the DJ in his younger days, leaning over albums as he reached for a mixing board, smiling at the world he created — one some of us aren’t courageous enough to imagine.