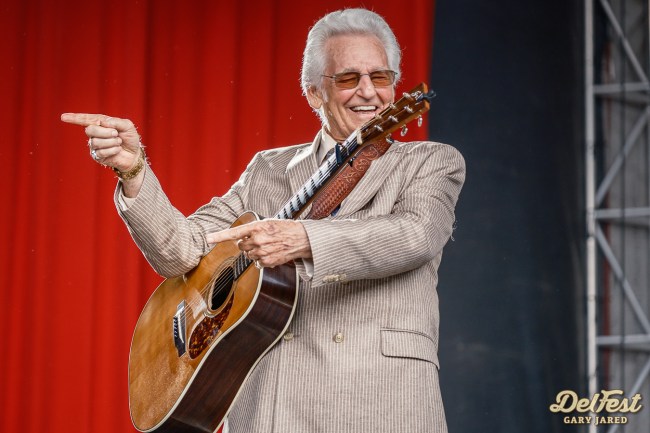

via Gary Jared / courtesy of Del McCoury / DelFest

“Hold on a second!” Del McCoury interjects with a chuckle, pausing our conversation to reminisce about a pivotal moment in his early career.

I had just mentioned to the 85-year-old bluegrass legend that I was from Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, about an hour down the Lincoln Highway from his hometown of York, Pennsylvania. As soon as I said ‘Chambersburg,’ Del’s memories came flooding back. It was a true ‘a-ha!’ moment.

“I’m going to stop you right there!” Del orders.

“The first time I played with any band of stature was in Chambersburg,” Del reminisces. “WCBG Chambersburg. The band name was Stevens Brothers, and those boys were from West Virginia. They’re brothers. And I was playing banjo with ’em.”

I could picture where the studio was, in an area of Chambersburg known to old-timers as Radio Hill because the studio and transmitter were there, perched above town.

It was a cool moment. Finding common ground with one of your music heroes is rare. I always thought it was neat that Del McCoury grew up in the same neck of the woods as me, the rural Pennsyltucky part of Pennsylvania sandwiched between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. But learning that his first gig with a band was in my tiny hometown in 1956 or ’57? Too cool. Maybe my grandparents heard it on the radio in passing? Man, who knows.

This unexpected connection set the stage for an intimate dive into Del McCoury’s illustrious career. Across six decades of making classic albums, including his latest release, Songs Of Love And Life, Del knows what he’s looking for in a song.

“I like a challenge. I’ve always liked a challenge,” he says. “I like to learn different things. Doing the same things is mundane to me.”

You can listen to my conversation with Del in the Apple Podcast player below on your device of choice, in the first episode of The Mostly Occasionally Show. Subscribe on Apple or Spotify!

“We Played the Ryman!”

I ask Del how his tour schedule has been lately.

Del begins, “We played the Ryman on Thursday, then we left and went to Evanston, Illinois—North Chicago, there. And then somewhere in Kentucky, and then we came back in on Sunday morning.” The Ryman show was a standout, featuring guest appearances from Lukas Nelson, Billy Strings, and John Oates. “It was a full house. We had about a 90-minute show roughly, and we ran over. I know we did.”

Billy Strings, the once-in-a-generation bluegrass phenom, often joins Del on stage for these appearances. Their collaboration dates back to 2018 when Billy and his dad sang with Del on that legendary Nashville stage—a moment Strings wrote about on Facebook as ‘a moment I’ll cherish forever.’ Since then, Del and Billy have recorded a studio cut of “Midnight In The Stormy Deep” and appeared together on all sorts of stages together.

Billy joined Del at Ryman Bluegrass Night this year to perform Bill Monroe’s “Can’t You Hear Me Calling.”

I ask him what it’s been like to watch Billy’s trajectory over the years. In just a few years, Strings has gone from playing mid-sized clubs and theaters to selling out stadiums and arenas, snowballing into one of the largest bluegrass acts of all time.

“He shot up there like a star or something, didn’t he?” Del marvels. Their collaboration began when Del’s agent booked Billy and his partner to open for Del at the City Winery in Chicago. “That kid was entertaining. He was not only just playing the guitar and singing. He was entertaining the people.”

Del McCoury on Mentoring Billy Strings

Del McCoury has a keen eye for talent, and it didn’t take him long to recognize Billy Strings’ potential.

“The first time I met him, you know the Dawg. David Grisman? He’s out there on the West Coast well, he called himself Dawg, Dawg music and all that. But me and him went out and did a bunch of just shows with duet. Just me and him, guitar and mandolin, we’d sing and this and that and there for a while of course. And we was all over the country with that little act. And then, anyway, one time my agent said, you now have got a guy, I’ve got another act that’s kinda like you and David. They play guitar and mandolin, and they sing. And he said, I want ’em to open for you at the City Winery in Chicago, I think was the first date.”

This encounter left a lasting impression on Del.

“I was sitting in the green room, back behind stage, and they were on, and I heard people applaud and I thought they really like this act, whoever it is. So I went where I could peep behind the curtain and nobody would see me, you know? And I was watching the show a little bit, and, hey, that kid was entertaining. He was not only just playing the guitar and singing. He was entertaining the people. And he wasn’t even 20 years old yet. Well, I guess he was, I don’t know. But I thought this kid’s got… He’s got it all.”

Del laughs, recalling Billy’s early days. “He had a cheap guitar back then. I almost gave him one of mine. But it wasn’t long before he started making money and could buy any guitar he wanted.” Del chuckles, clearly proud of his protégé. “He is doing great now. He is just… He’s a born entertainer.”

The Rise of Modern Bluegrass

Reflecting on the evolution of bluegrass, Del notes the impact of technology. “What I have noticed is there’s been so many bands spring up since those days, and with the internet and today kids, they can learn from their TV screen. They can learn… They can see chords, they can see how you pick, all that stuff. When I was growing up, the only way you had to learn it was either going to see a band in-person or listen to ’em on a 78 RPM record.”

“Earl Ran Up To The Microphone…”

Del’s own journey began with the banjo at age 11, inspired by the legendary Earl Scruggs. “I started playing banjo because I heard Earl Scruggs. But I learned a lot of things wrong until I saw him in person for the first time in 1955. Watching his right hand, I realized I was doing it all wrong,” Del laughs. “That one encounter set me straight and changed my playing forever.”

Del recalls vividly his first encounter with Scruggs. “I saw Earl… Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs in York County, near Lancaster, at a place called Valley View Park. My brother-in-law drove me there because I had to see this guy play. Earl ran out on stage and started playing ‘Train 45’ at what seemed like 600 miles an hour. That image of Earl has stuck with me ever since.”

Joining Bill Monroe’s Bluegrass Boys: “Chief, We’ll Take Del With Us!”

Del’s big break came when he joined Bill Monroe’s Bluegrass Boys after a chance encounter in a bar in Baltimore, where Del regularly gigged.

His memories of Bill Monroe are equally vivid. “Bill Monroe came in one night, and which surprised me, there was a side door in the place, and it’s kind of dark, you know how bars are. And I could see this guy in a big white hat, that white showed up in the dark. And I thought that looks like Bill Monroe, but he wouldn’t be in this place. I know he wouldn’t be in here.”

“I was playing with Jack Hook, a former Bluegrass Boy himself. Bill was looking for a lead singer and banjo player for a gig in New York City. Jack said, ‘Chief, we’ll take Del with us. He knows all the songs.’” Del chuckles, “We all called him Chief in the later years.”

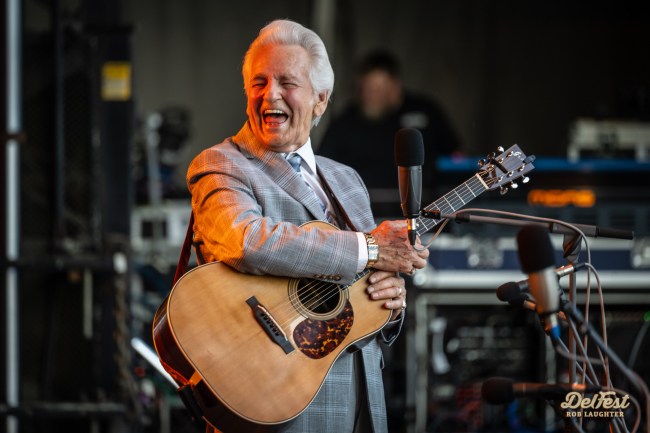

via Rob Laughter / courtesy of Del McCoury / DelFest

Del expected they would rehearse, but that wasn’t the case. “We tuned up and walked out on stage, and I had never played one note with Bill Monroe before. It was a kill-or-be-killed situation. But I had played banjo long enough to be comfortable trying new things on the spot.”

Bill Monroe offered Del a job, but initially, Del declined. “Bill was 52, which seemed old to my 22-year-old self. I liked playing with Jack, who was my age. But another musician convinced me not to pass up the opportunity. He even offered to drive me to Nashville.”

“That’s a good friend,” I remark.

“Sure is!” Del quips.

When Del finally joined Monroe, it marked a significant shift in his career. “Bill needed a lead singer and guitar player more than a banjo player. It was a challenge, but I took it. I never went back to playing banjo seriously after that.”

Del reminisces further, “Bill Monroe was an old guy to me back then, but working with him was something else. We never rehearsed, it was all about feeling the music. He’d just call up a song, and you had to jump right in. It was a test of your mettle every single night.”

Collaborations and his new album, Songs Of Life and Love

Del has always been open to collaboration. In 2011, he recorded an album with Preservation Hall Jazz Band called American Legacies, followed by a tour with the New Orleans legends. In conversation, I cite one of my all-time favorite projects, his 1999 collaboration with Steve Earle on the acclaimed album The Mountain, which was produced by his son Ronnie.

Recently, he recorded with Molly Tuttle on Songs Of Love and Life, showcasing his willingness to embrace new talent. “Ronnie said, you know what? We should get a girl singer. And I think that would probably be the best song. You can just take my voice off and put her on in my place.”

His latest album includes an intriguing cover of Elvis Presley’s “If You Talk in Your Sleep.”

“One time me and my wife were driving in the car and we had Sirius satellite radio on,” Del explains. “Well, this song came on and when it did, I thought, I’ve never heard that song and I liked that song.”

“I always like variety,” Del says. “I don’t have as many, I don’t do as many fast songs as I used to do years ago, but they’re hard to come up with. A good, really uptempo song is hard, is the hardest thing to find.”

“Willie Was Happening”

During our conversation, Del shared an interesting story about Willie Nelson and his son, Lukas Nelson.

“Well, I’ll tell you what,” Del begins. “We have a festival up in Cumberland, Maryland. We had booked Lukas Nelson, and I guess I had never heard Lukas before, but I knew his dad from when I was working with Bill Monroe. Willie was on the Grand Ole Opry back then, wearing a suit and tie, his hair slicked back, playing guitar, and writing songs for other people. He couldn’t get ahead until he went down to Texas. He called Waylon Jennings and said, ‘Waylon, you need to come down here to Texas. There’s something happening here.’ So Willie was happening, and it’s funny, the first song that put him on the map was ‘Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain,’ and he didn’t even write that song. But he had others he did write, you know?”

Del continues with a glow. “But Lukas, I didn’t even know about Lukas until we booked him at our festival. That kid can sing, man. He can really put it out there. He said to me, ‘I want to do something with you.’ I asked, ‘What do you think we can do?’ And he said, ‘We can do anything,’” Del laughs. “So we probably will, you know? We’ll probably do something together.”

I ask Del if there’s a place he’s always wanted to perform that he hasn’t yet.

“Not really, no,” he says with a chuckle. “As the saying goes, it’s just another day, you know? It’s a gig. People ask if I ever stop and look at sights in the cities I play. I tell them, ‘No, the only thing I see is the green room or the stage. Then I’m back on the bus and we’re gone again. As far as sightseeing, we never do much. It’s just whatever you see out the windshield of the bus.’”

—

No Set Lists and Audience Antics

I asked Del what keeps him motivated to keep getting out there on stage.

“Well, you know, I look forward to doing it, getting out on stage and singing and talking to the people. You know, I tell you, the audience entertains me more than I entertain them.”

“Really? How so?” I asked.

“They’re funny, man. If you just keep your ears open, they say funny things, you know?” Del chuckles. “I do a lot of requests. We never have a set list. We don’t know what we’re gonna do, so I’ll ask for requests. That song you mentioned, the ‘1952 Vincent,’ that’s probably my most requested song. But the funny part about it is, they forget the year. This past weekend, a guy said, ‘Do that 1959 Vincent.’” Del laughs heartily. “And I’ll say, ‘I don’t know that song.’ Then he’ll look at you, confused. I can’t leave him in suspense, so I say, ‘Now, I’ll tell you what I do know. I do know the 1952 Vincent.’ They just never get the year right. It’s never the 1952 model.”

“In the context of the song, the year is pretty important, too, because 1959 might not have been as good of a motorcycle,” I remarked.

“No, it’s not. It don’t rhyme either,” Del laughs again. “A guy told me, you know the guy that wrote it, it’s Richard Thompson. We booked him at our festival up there, and he told me, ‘You know, the ’52 Vincent didn’t have a key.’ In the song, when he wrote it, he handed the keys to Molly. He said, ‘I wondered how he was going to make this work. So I had to put keys in there to rhyme with whatever other word he had.’ A guy came up to me one time and said, ‘Hey, you know a Vincent didn’t have keys.’ I said, ‘Are you kidding me?’”

via Gary Jared / courtesy of Del McCoury / DelFest

The Legacy of “Don’t Stop the Music”

“Do you ever get, dare I ask, requests for ‘Don’t Stop the Music’?” I inquired.

“Yeah, I do a lot,” Del responded.

“That’s my mom’s absolute favorite song of yours.”

“Is it really?” Del said, sounding pleased.

“Yeah. My brother plays stand-up bass in a bluegrass band, and they cover it all the time. She loves hearing my brother sing it, as well as you.”

Del shared the backstory: “Oh, yeah, yeah. I’ll tell you about that. I played it once at the Opry. You remember Jimmy C. Newman?”

“Yeah,” I replied.

“So I go out there, and I do ‘Don’t Stop the Music.’ When I come off, Jimmy C. said, ‘I wrote that song.’ I said, ‘You did? I didn’t know.’ And he said, ‘Yeah, I’ll tell you what. I was doing shows with George Jones back in the ’50s. We’re both riding in the same car with some other guy. I had to drive all night one night. George was in the backseat, and I’ve got this song in my head, ‘Don’t Stop the Jukebox.’ I kept singing this over and over, thinking about writing more words for it.’ When we got to the next morning, George said, ‘You need to change that name. Call it ‘Don’t Stop the Music.’ It just so happened that George got into the studio before I did, and he cut my song. George sang it in waltz time. When I worked it up, I thought it worked better for us in straight time. So I’ve sung it that way ever since then. But Jimmy C. wrote it.”

“Yeah, Jimmy C. wrote it. And then after that, you had to give him a nod,” I remarked.

“Yeah, I did,” Del affirmed.

The Evolution and Future of Bluegrass

Curious about Del’s perspective on the genre’s evolution, I asked, “How do you see the evolution of bluegrass music? There are some wonderful stewards of the genre right now. How do you think about your role with those stewards, and how do you feel about the future of it?”

“It was kind of perilous at one time,” Del acknowledged. “I’ve always stuck to the same style. I never changed my style of playing or anything like that. But it was kind of stale back there. The Johnson Mountain Boys, when they came out, they were doing traditional style and were really good entertainers. That boosted it up again, back to the original style of music. Then the next boost I saw was when they made that movie Oh Brother, Where Art Thou? I was with Steve Earle when they did that. A lady called me to be in the movie, and I said, ‘Man, I’d love to do it, but I’m gonna be in Europe at that time.’ So I missed out on that. But then when they did the ‘Down from the Mountain’ tour, which was about that movie, they booked us, me and my band, for it. Naturally, they would book Ralph Stanley and Ricky Skaggs, and I forget who else, but they did the tour later. That was a really big boost for the music and it kind of kept it alive. It’s bigger now than ever. It just keeps growing, and the musicians and singers are, for the most part, better quality records in bluegrass now than there once was.”

“In the early days, there were certain ones that were really great, like Don Reno, Rickey Smiley, Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs, Bill Monroe, the Osborne Brothers, and Jimmy Martin, and Mac Wiseman. But that was about the extent of it back then. Now, there are so many great bands.”

“I think like, you know, back in the day, Jerry Garcia and the Grateful Dead did great stewardship of keeping bluegrass music and American roots music on the forefront of the culture,” I added.

“That’s right,” Del agreed. “Jerry and those boys, Peter, they were young guys, and people listened to them. They really boosted the music at that time.”

“Now, as a fan in my late thirties, there’s a songbook. It’s like jazz, where you know the songbook and the standards and the nuances between it. It’s a beautiful thing,” I reflected.

“It is. Absolutely is,” Del said with a nod.