As the rock’n’roll era took shape in the late 1940s, emerging from a raucous new blend of blues and jazz played for dancers in the night clubs of black America, the executives at major record labels initially turned up their noses. It was left to such figures as Art Rupe to exploit the opportunity and provide the means of getting the music to a wider audience via juke boxes and radio stations.

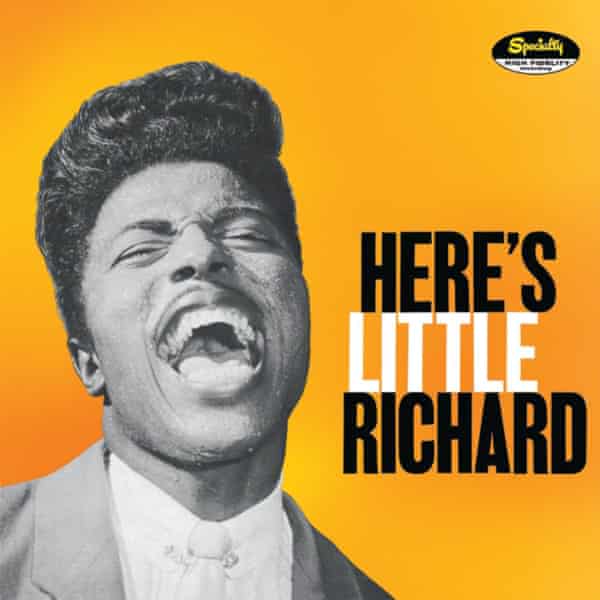

Rupe, who has died aged 104, was a record man, as the founders of such independent companies as Atlantic, Chess, Savoy, King and Modern were known. His own label, Specialty Records, became the vehicle for the early hits of Little Richard – including Tutti Frutti, Long Tall Sally and Rip It Up – and the recordings with which Sam Cooke conquered the gospel-music audience as the young lead singer with the Soul Stirrers.

Among Specialty’s other hit artists in a decade of success were the singers Lloyd Price, Larry Williams and Percy Mayfield and gospel groups including the Pilgrim Travelers and the Swan Silvertones. Knowledgable music fans of the time came to view the yellow, black and white label on a Specialty 78 or 45 rpm disc as a virtual guarantee of quality.

Born Arthur Goldberg in Greensburg, a suburb of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to David Goldberg, a secondhand furniture salesman, and his wife, Anna, Art was educated at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. In 1939, aged 22, he moved to Los Angeles, where he began studying business at UCLA with the intention of entering the film industry. His studies were interrupted by the second world war, during which he worked in a dockyard, repairing the Liberty ships that transported troops and equipment.

Failing to break into the movie industry, he tried the music business, changing his surname to a version of Ropp, the name of his German immigrant forebears. He helped found Juke Box Records, which had a national hit with RM Blues by Roy Milton and his Solid Senders before Rupe left his business partners to found Specialty in 1946.

He became a student of every aspect of the business, including the music. Carefully analysing current hits, he paid scrupulous attention to the quality of his own records. He believed in using studios with the best atmosphere and equipment, selecting the most accomplished musicians and treating them well in the studio in order to elicit their best performances.

“Above all technique does not mean anything if is the song is not sung and the music is not played WITH FEELING,” he wrote in a set of instructions to his employees. Such feeling was a hallmark of Specialty’s early hits in the renamed rhythm and blues chart, including Joe Liggins’s Pink Champagne, Mayfield’s Please Send Me Someone to Love and Guitar Slim’s The Things That I Used to Do.

On a trip to New Orleans in 1952 he recorded the teenaged Lloyd Price singing Lawdy Miss Clawdy, which was named R&B record of the year. New Orleans became a fruitful source of material and three years later he sent the producer Robert “Bumps” Blackwell to the city to record Richard Penniman, a singer from Macon, Georgia, whose voice he had heard on a demo tape. In the last 15 minutes of the three-hour session they recorded a cleaned-up version of a salacious song called Tutti Frutti, with which, as Little Richard, Penniman would finally make the sound of rock’n’roll match the older generation’s worst fears.

In common with most of his competitors, Rupe paid extremely low royalties, telling his artists that hit records would raise their income from live performances. But at least he usually paid up, unlike some, although in 1959 Little Richard sued him and was awarded $11,000 in back royalties. Rupe was unusual in his detestation of the widespread bribery of disc jockeys. Known as payola, the system was at its height in 1957 when he responded to a particularly outrageous demand by cancelling the appearance of one of his artists on the nationally televised American Bandstand show.

That same year Little Richard told the world that he was renouncing show business to enter the church. Almost simultaneously, Sam Cooke was heading in the opposite direction. Rupe, who loved the way gospel-trained singers brought raw emotion to pop music, was not pleased when Cooke recorded a set of ballads in a smooth style that he considered bland. His reaction was to release the singer from his contract and allow him to take the rejected recordings elsewhere. One of the songs, You Send Me, was soon shooting to the top of the national charts on another label and laying the foundation for Cooke’s huge success as a solo artist. It was an expensive decision for Rupe, but one based on a refusal to compromise his musical standards.

He stepped back at the end of the 50s to pursue business interests in oil and land, and in 1990 he sold Specialty and its rich catalogue to Fantasy Records. Having returned to UCLA to complete his degree, he set up the Arthur N Rupe Foundation, which supported projects under the rubric “creative solutions for societal issues”. In 2011 he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Rupe married three times. His third wife, Dorothy, predeceased him. He is survived by a daughter, Beverly, from his second marriage, to Lee Apostoleris, which ended in divorce, and by a granddaughter, Madeline.