As a kid growing up on the outskirts of Manchester, England, John Mayall recognized something personal in the blues records coming over from the United States. He heard joy, agony and stories from real life, all of it set to music that could be euphoric and downtrodden, hopeful and mysterious.

It was music of profound emotion that would stay with him forever, and as a leading purveyor of that tradition in the British blues explosion of the 1960s, he represented a standard for many better-known players to follow. “He was my mentor and a surrogate father too,” Eric Clapton said in a tribute posted Wednesday on Instagram. “He taught me all I really know and gave me the courage and enthusiasm to express myself without fear or without limit.”

Mayall, who died this week at age 90, provided a home to an astonishing lineup of virtuosic players who passed through his band the Bluesbreakers en route to greater fame later: Clapton and Jack Bruce (who formed Cream), Mick Taylor (later of the Rolling Stones) and members of Fleetwood Mac, Journey, Canned Heat and more.

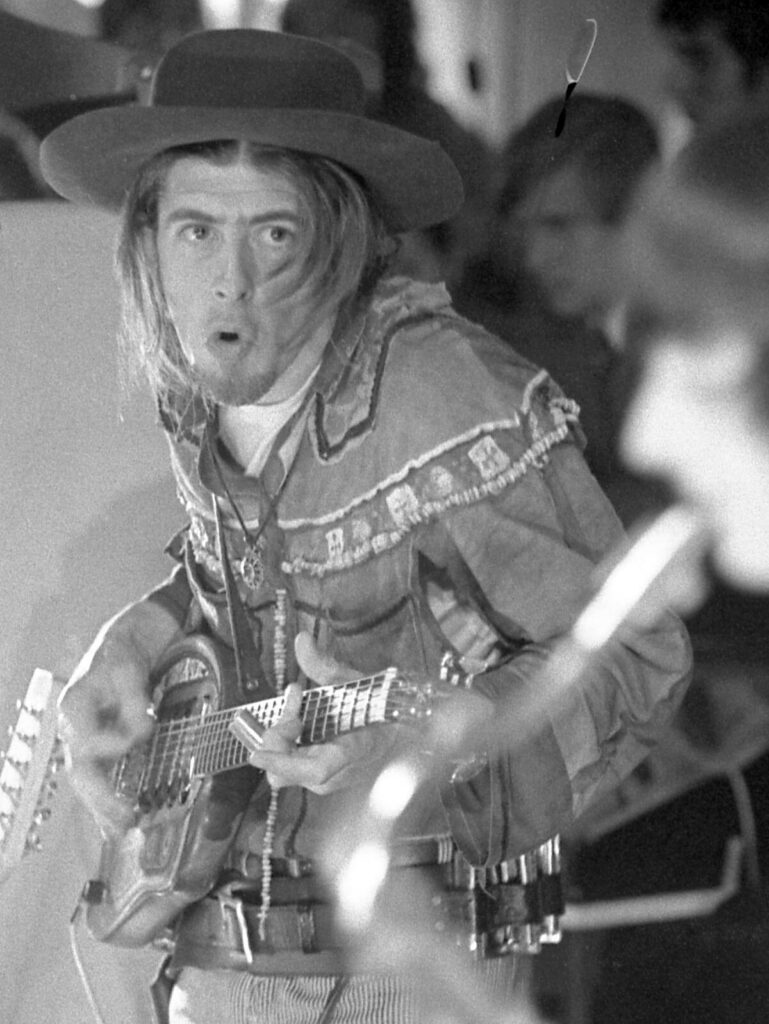

John Mayall was a mentor to Eric Clapton, Mick Fleetwood and many other superstars.

(Claus Hampel / Associated Press)

He was a half-generation older than many of the iconic players he nurtured, and an important source of inspiration. He gave refuge to a disheartened Clapton, who had just quit the Yardbirds and was considering leaving music entirely. But the fame that many of Mayall’s endlessly rotating sidemen later enjoyed was entirely beside the point to him.

“The great roster of the most famous names all came out of that period of London of four or five years,” he told me in 1997. “Everybody knew everybody, so they were shifting around, finding their own musical path. As a band leader I just hired whoever turned me on. That criteria is the same today as always.”

Back in the 1990s, I interviewed Mayall a few times, including at his house in the San Fernando Valley. Our very first talk on the phone was cut short by him after about 15 minutes, probably from my own inexperience as an interviewer and for asking too many questions about his more controversial statements. (Like calling Led Zeppelin “a parody of the blues.”)

But he was normally a patient proselytizer of the blues. While his own reputation often rested with his role as a profoundly gifted scout of talent, his own records showed a steady commitment to what had first inspired him. Mayall was a singer and multi-instrumentalist (harmonica, keyboards, guitar), and like his heroes, the songs he wrote were autobiographical — celebrations and laments about his life experiences.

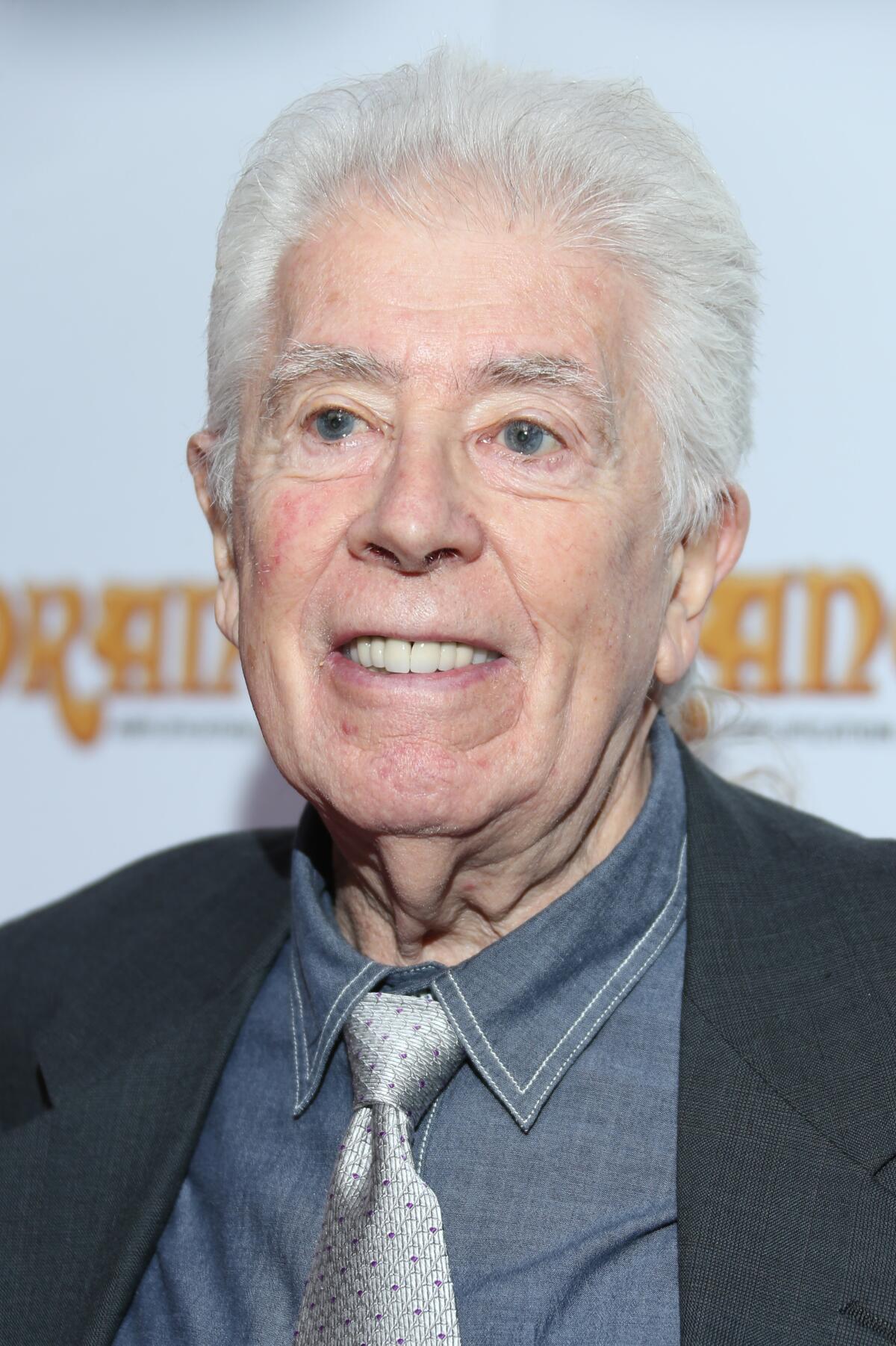

John Mayall in 2013 at the Classic Rock Roll of Honor Awards show in London.

(Joel Ryan / Invision/Associated Press)

He was sometimes criticized as a purist who rarely wavered, even as former collaborators won accolades and made hit records by straying into rock, psychedelia and pop. If anything, his experiments went further away from the masses with a jazz-rock fusion sound on 1968’s “Bare Wires.” He stretched out with layers of horns and flute, he went solo acoustic, but the electrified Chicago blues was always his North Star.

“‘Purist’ is a funny word really, because it can mean someone who doesn’t want to shift from doing note-for-note copies of stuff other people have done in the early days,” he said. “There are bands that just do that. They consider themselves blues purists. But I’ve always been an innovator, so purist doesn’t really fit.

“I do draw from the pure roots of the blues to make something that’s very contemporary and something that is very personal.”

He grew up in the late-1940s and ’50s listening to his father’s vast record collection, learning to love the Mills Brothers, Charlie Christian and Lonnie Johnson, and was soon saving up to buy his own 78 rpm discs. “Anything with the word ‘boogie’ on it, I bought it,” Mayall told me. He then discovered the immortal blues played by Big Bill Broonzy, Blind Lemon Jefferson and Sonny Terry.

He was already 30 when he left Manchester for London, after a career in typography and art, ready to join the blues scene rising there. “It all really happened rather suddenly, and everybody really came down to London,” he said. “The Animals came down from Newcastle, Spencer Davis and Stevie Winwood came from Birmingham. If you wanted to play you really had to start off and be based in London. So that’s what I did.”

The British blues scene was kicked off by Alexis Korner and Cyril Davis, evolving from folk clubs to electrified Chicago blues. As it had for Mayall, American blues had reached the postwar generation on the British Isles and ignited a movement, even as blues was still underappreciated back in the U.S. It would take a British invasion of inspired young players to bring it back home.

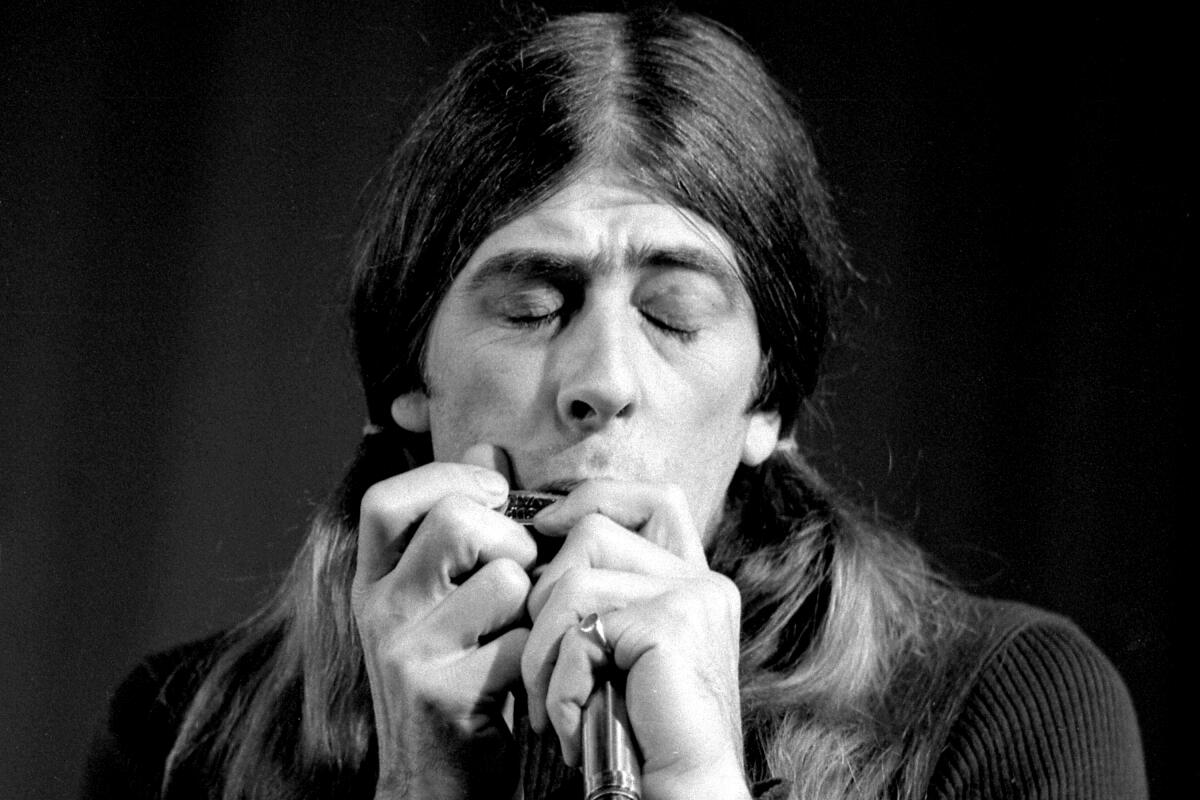

Mayall was a singer and multi-instrumentalist (harmonica, keyboards, guitar), and like his heroes, the songs he wrote were autobiographical — celebrations and laments about his life experiences.

(Claus Hampel / Associated Press)

In those early days, Mayall was encouraged by successes of the early Rolling Stones and Yardbirds. “I was pretty amazed, because I had been playing this music privately for 15-20 years and knew what it was all about. But I’d never dreamed it was fit for public consumption, so to speak,” he said. “I owed it to myself to give it a shot.”

His best-known album, 1967’s “Blues Breakers With Eric Clapton,” is considered a classic document of that scene, and an early sign of Clapton’s still evolving skills. Mayall otherwise had no major pop hits, and few accolades for most of his life other than a couple of Grammy nominations. In 2005 he was awarded an OBE (Officer of the Order of the British Empire) by Queen Elizabeth II, and this fall was to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame with an Influence Award.

At times during interviews, he would grumble about a lack of recognition, but his focus remained on the work ahead — spending a third of the year on the road, and releasing nearly 40 studio albums and more than 30 live recordings in his lifetime. For him, his musical journey remained always open-ended, right up until his last performance in February 2022 in San Juan Capistrano.

“Creating music is an art,” he explained. “Jazz musicians and blues musicians, their careers do not end except by death. It’s something that has a built-in longevity. It’s not a flash-in-the-pan thing. The years only make you more mature, you learn more and more as the years go by.”