Christine McVie, the singer, songwriter and keyboardist whose dreamily optimistic tunes for Fleetwood Mac — including such FM-radio staples as “Don’t Stop,” “Little Lies,” “Songbird,” “Everywhere” and “You Make Loving Fun” — helped make the band one of the most successful acts in music history, died Wednesday. She was 79.

Her death was announced by her family in a statement that said she’d “passed away peacefully” at a hospital following “a short illness.” The statement didn’t specify the hospital’s location. McVie, who lived in London, told Rolling Stone in June that she was in “quite bad health,” describing a chronic back problem that made it difficult for her to stand.

“There are no words to describe our sadness at the passing of Christine McVie,” Fleetwood Mac said on social media. “She was truly one-of-a-kind, special and talented beyond measure. She was the best musician anyone could have in their band and the best friend anyone could have in their life. Individually and together, we cherished Christine deeply and are thankful for the amazing memories we have. She will be very missed.”

Christine McVie, a member of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame band Fleetwood Mac, rehearses with band mate Lindsey Buckingham at Sony Studios in Culver City in May 2017.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

In a famously fractious outfit filled with competing songwriters — Fleetwood Mac’s classic lineup also included singers Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks along with drummer Mick Fleetwood and bassist John McVie, to whom she was once married — Christine McVie was perhaps the most gifted hitmaker, with a natural flair for melody and a lithe, soulful voice that seemed to send her songs sailing out into the world. “I don’t struggle over my songs,” Rolling Stone quoted her as saying in 1977. “I write them quickly.” Onstage, her steady presence behind the keyboard provided a crucial counterweight to the more dramatic figures cut by Buckingham and Nicks, whose rocky romantic relationship powered the band’s darkly glamorous legend.

She also served as a kind of connective link between Fleetwood Mac’s early days as a British blues-rock combo and its commercial peak as a Los Angeles-based soft-rock act in the 1970s and ’80s. Among the other well-known songs she wrote for the band were “Hold Me,” “Think About Me” and “Say You Love Me,” which typified her breezy yet sensual approach. “When the loving starts and the lights go down / There’s not another living soul around,” she sang over a gently rollicking groove, “You woo me until the sun comes up / And you say that you love me.” Fleetwood Mac won album of the year at the Grammy Awards in 1978 for “Rumours,” which has sold more than 20 million copies in the United States alone; the band was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1998.

Nicks posted a handwritten note on Instagram on Wednesday in which she called McVie “my best friend in the whole world since the first day of 1975″ and said she hadn’t learned that McVie was sick until Saturday night. She finished her note by quoting the lyrics of “Hallelujah” by the L.A. sister trio Haim, which wrote in its own Instagram post that “the sisterhood Stevie and Christine had was so vital to us growing up.”

Christine McVie with Fleetwood Mac in 2014.

(Arthur Mola / Invision / Associated Press)

McVie was born Christine Perfect on July 12, 1943, in the village of Bouth in northwestern England. Having learned to play piano as a pre-teen — her father was a music professor, her mother a psychic — she joined the band Chicken Shack in 1967 and scored a modest hit with a cover of Etta James’ “I’d Rather Go Blind.” She married John McVie in 1968 and joined Fleetwood Mac in 1970, not long after releasing a debut solo album called “Christine Perfect”; after a series of personnel changes involving the group’s frontmen, Buckingham and Nicks arrived in time for Fleetwood Mac’s self-titled 1975 LP.

“Rumours,” with its careful balance of high-stakes emotion and rich-hippie iconography, documented the fraying of numerous relationships within the band, including that of the McVies, who divorced in 1976. (The flirty “You Make Loving Fun,” as the story goes, grew out of her affair with the band’s lighting director.) McVie continued playing with Fleetwood Mac throughout the late ’70s and ’80s — “Hold Me,” from 1982’s “Mirage,” was inspired by her relationship with Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys — and she released a second solo album in 1984. She married Eddy Quintela, a Portuguese musician, in 1986; the couple co-wrote “Little Lies” for the next year’s “Tango in the Night” album and divorced in 2003.

A reluctant traveler who spoke frequently of her fear of flying, McVie opted out of touring with Fleetwood Mac to support 1995’s poorly received “Time,” though she did perform “Don’t Stop” with the band’s other key members at President Clinton’s inaugural ball. She later took part in “The Dance,” a hugely successful live album released in 1997, after which she quit the band and moved to the English countryside.

Christine McVie, left, and Stevie Nicks in 1977.

(Rick Diamond)

She surprised fans by returning to Fleetwood Mac in 2014 for a lengthy reunion tour. “I’d been virtually doing nothing in the country in 16 years of being a retired lady,” she told The Times in 2017. “Being busy walking my dogs — actually not doing anything very constructive.” (In 2004, she released “In the Meantime,” which she called a “little solo album” she’d made in her garage.) After the tour with Fleetwood Mac, she recorded a duo album with Buckingham at the Village Studios in West L.A. — the same room where Fleetwood Mac laid down 1979’s “Tusk” — before hitting the road again for another round of full-band gigs. In 2018, Buckingham was fired from Fleetwood Mac and replaced by Neil Finn of Crowded House and Mike Campbell of Tom Petty’s Heartbreakers; the group’s most recent public concert was in 2019. This year, the wistful funk of “Everywhere” has gained new life as the soundtrack to a widely seen car commercial, driving the song to more than 580 million streams on Spotify alone.

Information on McVie’s survivors wasn’t immediately available.

In a 2014 interview with The Times, McVie recounted how she got over her fear of flying, which she said involved gradually desensitizing herself to the idea; the breakthrough arrived when Fleetwood accompanied her on a flight to Maui, where she sat in with the drummer and her ex-husband at a performance by their blues band.

“I did a couple of songs there, it felt good onstage, and then I thought, ‘I’m really missing out on something — something that’s mine, that I’ve just given up, and I’m not paying respect to my own gift,’” McVie said. “I saw that if I want to start to play again, there’s only one band I want to play with, and that’s Fleetwood Mac.”

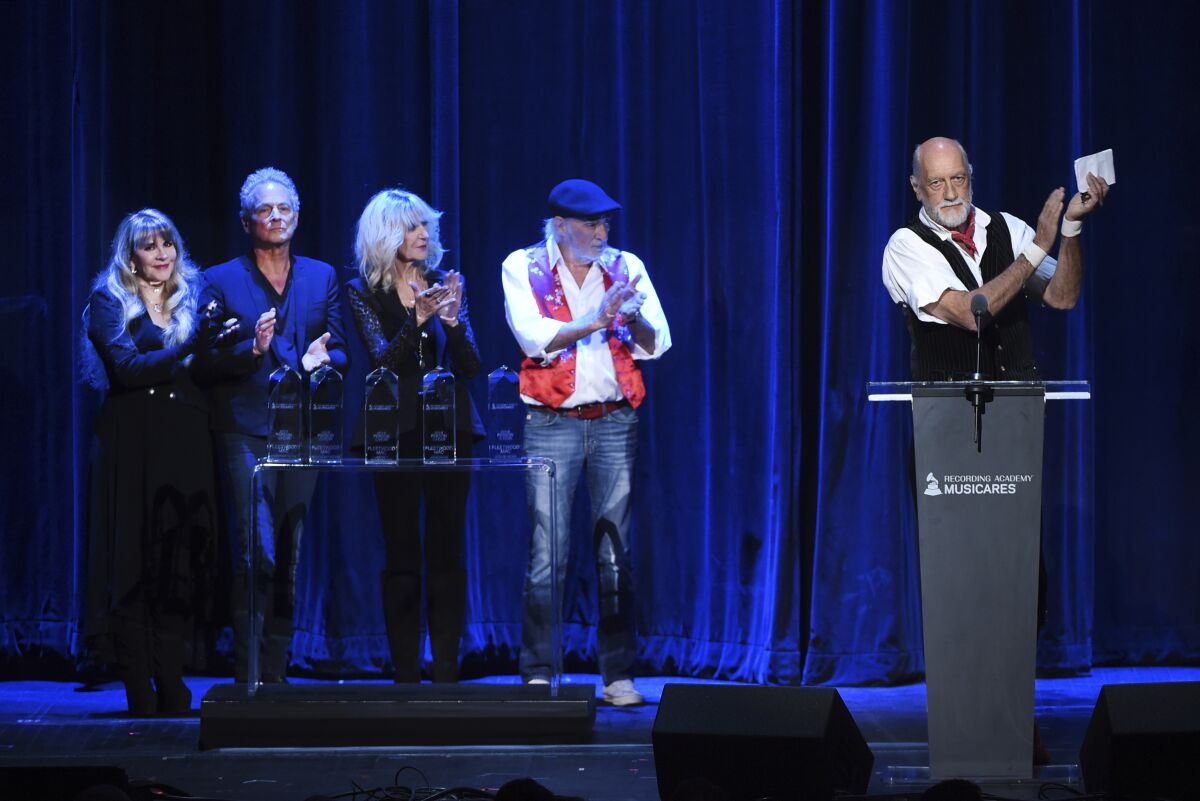

Stevie Nicks, from left, Lindsey Buckingham, Christine McVie, John McVie and Mick Fleetwood, at podium, during the 2018 MusiCares Person of the Year tribute honoring Fleetwood Mac.

(Evan Agostini / Invision / Associated Press)