When Pentiment launched on Xbox and Game Pass a couple of weeks ago, my social media feeds were inundated with trusted friends and colleagues ranting and raving about the game. Curious, I checked it out for myself and discovered that this is one of those times when we’re just gonna have to agree to disagree. I’m well into the game’s third act, and I still can’t figure out what it is about Pentiment that caused so many friends and colleagues, whose opinions I value and whose tastes are, on the whole, similar to mine, to love this game so much. But I think I have some clues.

In trying to tease out the reason for Pentiment’s popularity, I wondered, at first, if it could be the gameplay.

In Pentiment, you play as Andreas Mahler, a painter working on illustrated manuscripts in an abbey in Bavaria in the 1500s. The gameplay loop unfolds over the course of several days in which Mahler wakes up, goes to work, eats with his friends and colleagues in town, and goes to bed. And while the cast of characters is interesting from a historical perspective — the game presents interesting takes on the kinds of people living in a rural town in the early tumultuous days of the Protestant Reformation — it’s all pretty boring because the only thing you can do is talk.

Pentiment started showing signs of life when Mahler’s daily routine is broken up by a murder he takes upon himself to solve in order to save an innocent friend from execution. The game got a little more interesting when I had to choose which time-consuming activities to pursue in order to find the killer. If I chose to assist the town’s curmudgeonly widow in order to pump her for information, I wouldn’t have time to hear the potential clues hidden in the juicy gossip shared at the town’s wool spinning bee.

Image: Obsidian Entertainment

I also appreciated how your own biases against characters inform how you solve the murder. Before the murder, the town widow cursed the victim and wished him dead, so I, naturally, wanted to know what was up with that. Her rude outburst led me to suspect her and then question her, which led me to even more clues that made her look guilty. In pursuing that thread, and with the limited time available, I had no choice but to choose her when it was time to name the killer even though there were other likely suspects. Pentiment isn’t Ace Attorney, so infuriatingly — in the good kind of way — the game never tells you if you got the right person (sorta).

There are also moments in which a dialogue choice influences a character and informs how they react and what they’ll share with you. Just like in real life, there’s no way to tell which innocuous phrase will trigger the anxiety-inducing “this will be remembered” message.

I enjoyed how Pentiment forces you to live with your choices in ways that other games, which make their bones on being about player choice (paging Mass Effect), do not. There’s no way to save scum and go back to change what you say or do to get a desired outcome. You can go back and save Wrex on Virmire, but you can’t take back snapping at a child for stealing your hat, which has butterfly effect-like consequences on how you decide who deserves to hang for murder.

I enjoyed how Pentiment forces you to live with your choices in ways that other games, which make their bones on being about player choice (paging Mass Effect), do not

That’s basically all there is to Pentiment, though. Somebody dies, and you, through your choices, decide who’s guilty. And while I appreciated Pentiment’s deft display of how the littlest things we do or say or our internal biases can have far-reaching life-and-death ramifications, the act of how those lessons were unfolded to me as a player was just… blah.

I think one of my biggest hang-ups about Pentiment is that, in all the buzz I saw about it, the fact that it’s a visual novel was never mentioned. There’s nothing wrong with visual novels or games that are purely narrative, but I have to be in the right mindset for that kind of game so I can modulate my expectations. And even then, a lot of visual novels have more gameplay substance to them than just “talk and make choices.” I figured that once the murder investigation got underway, I’d be presented with little mini-games that would help me discover clues. Early on, I picked studying nature as one of Mahler’s backgrounds, so I thought maybe there’d be some kind of puzzle I could solve identifying local plants that might help me somehow later in the story. I just needed something, anything, to break up the monotony of talking at great length to NPCs, but I never got it.

So if it’s not gameplay that’s causing all the Pentiment propaganda, maybe it’s the story?

As I said before, the game presents some pretty novel takes on the interior lives of people circa Martin Luther and the “I got 95 theses and a Pope ain’t one” bars he dropped — or more accurately nailed — on the Catholic Church. There is a pleasing diversity of thought, religion, and physical appearance. I was delighted to see the game included an African priest from Ethiopia, a Jewish couple, and a dark-skinned Romani man when the game could have just as easily been 100 percent lily white. Whiteness in service to “historical accuracy” has always been a myth, and Pentiment rightly challenges that myth. If a game set smack dab in the middle of friggin’ Germany anno domini 1518 can include Black people, a game featuring dragons and demons based on nothing but Europe and vibes can also have folks on the darker side of the paper bag.

The female characters in Pentiment are also great because they encompass the length and breadth of the female experience at that time. They’re not all poor, dirty housewives (another pernicious “historical accuracy” myth) but, rather, educated, employed, business-running women. There are women of power and wealth and ambition who either recognize and lament the unfairness of their gender’s second-class status or do the best they can to work within or break the system. There’s a nun at the abbey who, unlike her sisters, chafes at the bonds of her vow. She scolds Mahler when he chastises her imperiousness, saying that her life sucks, she didn’t choose it, and were she born a man, she’d have the freedom she desires and deserves. There’s also another nun who, after breaking her vows with a monk, decides to just leave the convent, marry the monk, and live as a layperson.

I loved getting to know the characters and seeing their lives evolve over the years the game takes place. But each of the game’s murders unfolds at such a slow pace that it’s reasonable to just give up before the bodies hit ye olde floor. When I first started playing, my husband would drop in and ask “has anything happened yet?” every 30 to 45 minutes, to which I’d balefully respond “no.”

I’m not against giving a game time to tell me what it needs to at its own pace, but my patience has limits. And after a while, since you stay in the same place with the same gameplay loop, even the colorful characters start to lose their luster. There are only so many times you can say “God bless you” to the blacksmith or eat lunch with the abbey’s stuffy monks before it’s not interesting anymore.

So if it’s not the gameplay and only partly the game’s story, could it be Pentiment’s art that’s causing the kerfuffle?

Holy shit (Lord, forgive me). Yes.

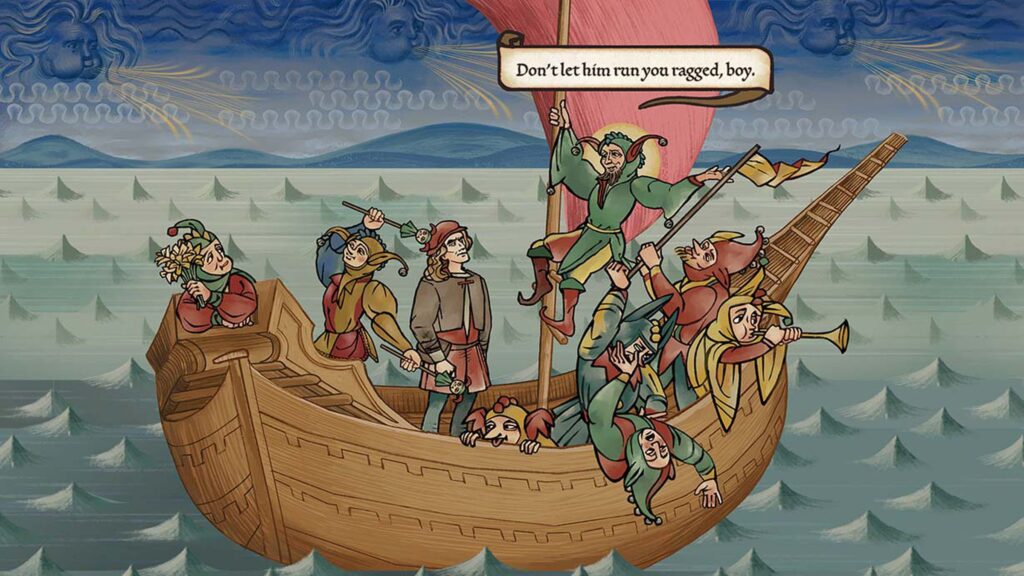

Pentiment’s art is stunning. Everything about this game’s visuals is so thoughtfully detailed and rich, enhancing the story and making you feel like you’re reading one of Mahler’s illustrated manuscripts. The game is presented like a book. Each screen transition flips a page of the book, and when that happens, you can see ancient script bordering the screen like the game’s just an illustration in Le Morte d’Arthur or The Canterbury Tales. It’s a shame Pentiment came out too late to qualify for this year’s Game Awards because it would handily sweep every art category.

The font of the game’s dialogue is also brilliant, as it changes based on who you’re talking to and your knowledge of them. Peasants talk in a handwritten script with frequent typos that get erased and corrected, illustrating their low education. When you find out one of the so-called “peasants” knows how to read, their font changes to book type to reflect their learnedness. The same way your biases can decide a person’s guilt or innocence, your biases influence how you literally perceive a person. Do they have the typo-ridden script of a peasant or the florid gothic hand of a learned priest? It’s utterly brilliant. 10 out of 10. No notes. And if super fancy fonts are too hard to read — as they were with me after a while — there’s an accessibility feature to change them into a more easily readable type.

Pentiment may not have hit for me, but it is, by no means, a bad game. I put in 12-plus hours, despite questioning every single minute, because there’s just enough (and I mean just enough) of a compelling story and characters to get me over the game’s hurdle of boring.