Alejandro G. Iñárritu is fond of a Facundo Cabral song called “No Soy de Aqui, Ni Soy de Allá,” which translates to “I’m Not From Here, nor From There.” It’s a bittersweet ballad of existing in between life’s lines: “I have neither past nor future, and being happy is the color of my identity.”

The filmmaker, a two-time Oscar winner for director, can relate.

Iñárritu’s new film, his most personal to date, is “Bardo, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths.” The bardo, in Tibetan Buddhism, is a state of existence between death and rebirth, the kind of liminal place that the filmmaker has thought about a lot. Born in Mexico City in 1963, he shot out of the gate in 2000 with the Mexican-made “Amores Perros,” then decamped for Los Angeles and a series of increasingly lauded American movies, including “21 Grams” (2003), “Babel” (2006), “Birdman” (2014) and “The Revenant” (2015).

“We thought that we would be one year in California, then 21 years passed like one week,” he says in a video call from Lyon, France, where he was showing the new film. “You are there, and you belong to this immigrant and hybrid culture. Beyond the success or failure of that adventure, no matter what, the experience comes with beautiful and great opportunities. But at the same time, a lot of it takes a toll, and there are a lot of things that you lose. There are contradictions, uncertainties and paradoxes.”

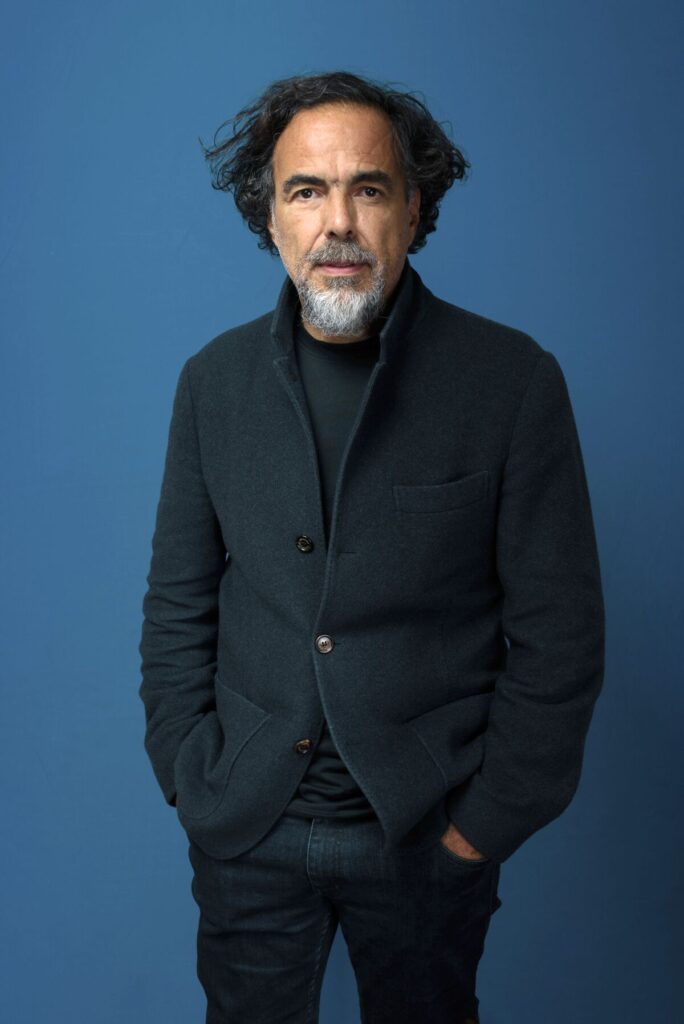

Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu

(Christopher Smith / Invision / AP)

Iñárritu speaks in a geyser of ideas, one blurring into the next. His films often create the same sensation. In “Bardo,” a celebrated journalist and documentary filmmaker, Silverio Gacho (Daniel Giménez Cacho), returns home to Mexico City from Los Angeles to receive a major award. He traipses into moments from his personal past, Mexican history and dreamlike combinations of the two, including an elaborately theatrical reenactment of a battle from the Mexican-American War (“That was not a war, it was an invasion, as you know,” Iñárritu says). Silverio absorbs barbs, some congenial, some less so, from old friends and colleagues who consider him a sellout or a snob. In one scene, in a public restroom, he encounters his late father and shrinks down to the size of a little boy.

Giménez, the actor who plays Silverio, was happy to come along for the surreal ride. He recalls the advice Iñárritu gave him: “Just be present and let it flow. There is no character. You don’t have to behave in this way or that way. It’s all about you and how you are you in this present.

“This was a great experience for me,” Giménez says. “I felt I grew while I was working. It was joyful and fantastic.”

With echoes of Fellini’s “8 ½” and some of Iñárritu’s favorite Latin American magical realist authors — Jorge Luis Borges, Juan Rulfo, Gabriel García Márquez — “Bardo” reflects the inner journey of both the man on the screen and the man behind the camera. The film is a series of rapturous images, threaded together by subconscious logic.

“I feel like the more I say about this film, the more I betray it,” Iñárritu says. “How to explain the atmosphere of a dream? I feel that when you explain a dream, you are ripping it apart. I try to not demand logic in a dream, because there’s no space for logic. If people arrive to watch the film with their autopilot, rational mode, demanding logic, it will be a frustrating experience.”

Many critics found “Bardo” to be a frustrating experience when it premiered at the Venice Film Festival in September. “Self-indulgent.” “Meandering.” Iñárritu took exception, arguing at one point that such language wouldn’t be used if he wasn’t Mexican. “If I maybe was from Denmark or if I was Swedish I would be a philosopher,” he said at the time. “But because I did it in a powerful way visually I am pretentious because I’m Mexican.” He lamented what he saw as a “racist undercurrent” to criticisms of the film.

Today, he’s a bit more sanguine. “I never made this film thinking of a novice,” he says. “I made it for very deep personal reasons. That’s a very extreme need at my age. After the films that I have done, I felt the right to express the way I wanted to express myself. And I always have confidence that the film will find the right audience.”

Through all of the film’s subconscious probing, Iñárritu also wanted to explore a subject that continually finds its way into the news: the immigrant experience. Silverio feels out of place wherever he goes, in his native land or his adopted home.

In one scene, when he returns to Los Angeles with his family, a Latino customs agent tells Silverio he does not, in fact, live in the U. S. The Kafkaesque incident ends with Silverio being dragged out of the airport, literally kicking and screaming.

“I felt the need to talk from my personal perspective and personal experience about what that experience is for me, and how I can reflect that and talk about the universal phenomenon that is the consciousness of being an immigrant, from my perspective,” Iñárritu says. “That is the only perspective that I can talk from honestly, no matter who I am. It was something that I needed as a catharsis.

“But the fabric of this is made of things that we cannot grasp, that you cannot explain. That’s why you make a film.”