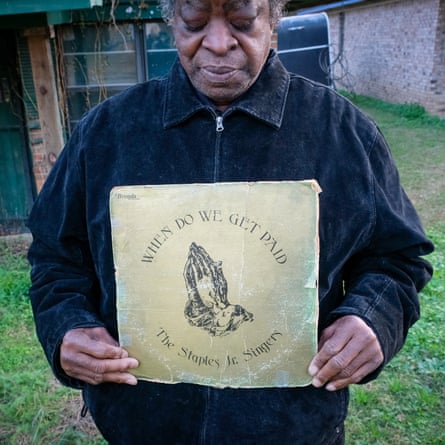

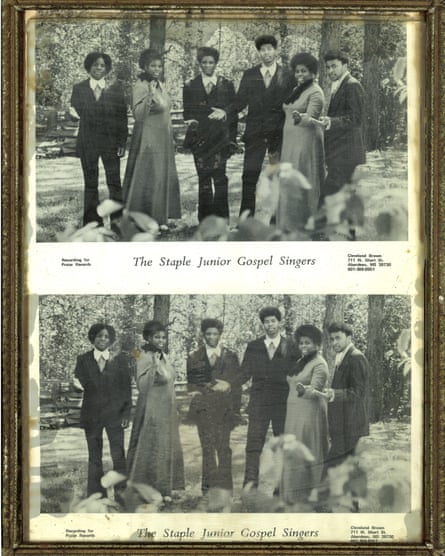

In 1975, a group of teenage siblings in Aberdeen, Mississippi, recorded an album of gospel songs focused on toil, conflict, succour and redemption. They named themselves the Staples Jr Singers in tribute to Mavis and co, their Mississippi forebears, because “a lot of Staples songs had a meaning to them”, says Annie Caldwell (then Annie Brown). She was 14 when they released When Do We Get Paid, although the album’s title track could serve as an anthem for any adult who finds themselves overworked and under-compensated.

They made 500 copies of the album, which they sold at performances and in their front yard. Once they sold out, they didn’t consider pressing more. “We were busy getting on with life,” says Edward Brown (their brother ARC completed the group). “Gospel was something we sang because we love to praise the Lord. Not some kind of show business.”

That is how things would have remained had Luaka Bop, the label founded by David Byrne, not chanced upon a 45 the Staples Jr Singers had released in 1973. After tracking down the members, they included the song on the 2019 compilation The Time for Peace Is Now (Gospel Music About Us), an album that gathered rare soul-gospel 45s from the 1960s and 70s, all with themes of social consciousness. In May, the label reissued the group’s lone album, which immediately gained attention for its direct and powerful performances.

“We were raised in the church and our father was a fine gospel singer,” Edward explains of their approach. Caldwell says, “I can be a witness. Some people just sing just to be singing, but back then you could feel it. You were basing it on yourself. Singing about what was going on around us. What our parents were going through to put food on the table. All the hardship and hurt. And how the Lord does guide us and provide a helping hand – how he is always there if you reach out to him.”

They remained the Staples Jr Singers until the 1980s when Caldwell, having married and started a family, began singing with her daughters as the Caldwells. Today, the original band members work day jobs and sing in church. But this month, they take the stage at the London jazz festival, the group’s first ever show outside the US. New to interviews, and polite but somewhat guarded, Caldwell and Edward Brown struggle to explain how When Do We Get Paid came to be on Luaka Bop. Label co-owner Yale Evlev explains: “Greg Belson, a British record collector who’s now based in LA, has been gathering these very rare gospel 45s and it was he who compiled The Time for Peace Is Now. Lots of the artists on Time for Peace only cut 45s so when Greg bought a copy of When Do We Get Paid from another collector and sent us the files, everything came together.”

Tracking the group down, however, proved harder. “Beyond a few Black music labels like Savoy, Chess and Stax, who set up gospel imprints because they understood their customers attended church, most gospel releases were and are homemade,” says Evlev. “Tracing the Browns involved some sleuthing and it was our graphic designer who worked out that Annie Brown was now Annie Caldwell. There are seven Annie Caldwells in Mississippi and I had called six and got no response. I called the seventh and was about to leave a message when Annie picked up.”

The label brought the trio to New York to perform. “As soon as Edward opened his mouth, I knew the Staples Jr Singers had lost none of their power. They were so young when they made that album so they’re still performing strongly.”

Secular interest in gospel has been growing apace in recent years. London’s Honest Jon’s Records has issued the epic six-LP set A Stranger I May Be: Savoy Gospel 1954–1986 and Christians Catch Hell, an overview of funky Florida gospel from 1976-79. Earlier this year, Luaka Bop issued Pastor Champion’s I Just Want to Be a Good Man, a 2018 live recording of an itinerant preacher and gospel singer. US labels Numero, Tompkins Square, Dust to Digital and Buked & Scorned have all made remarkable “lost” gospel music available. Meanwhile, Kanye West has employed the likes of Budgie – another LA-based, British-born crate-digger – to source gospel samples.

Where crate diggers once discarded gospel records, they are now becoming as valued as rare soul or ska 45s. In Waco, Texas, Baylor University’s Robert Darden oversees the Black Gospel Music Restoration Project, which aims to preserve every known recording. Jerry Zolten, author of Great God A’ Mighty!, a fascinating overview of the rise of soul-gospel, and the narrator of How They Got Over, a Grammy-nominated documentary on gospel’s role in shaping rock and R&B (currently streaming on Amazon, iTunes and HBO), is gratified by this new wave of secular enthusiasm, which he credits to streaming. “Black gospel as foundational music is really beginning to sink in,” says Zolten.

That secular gospel enthusiasts don’t tend to get excited by the likes of Kirk Franklin – a mainstream US star whose albums make the Billboard 200 and who commands a vast, church-going African American audience – suggests a split in the genre.

“I admire Kirk Franklin but his contemporary style simply does not move me in the same way that old-school gospel does,” says Zolten. “For me, somewhere in the 60s, African American tastes shifted more to soloists over gospel choir music and they don’t speak to me as much as the earlier groups. That there was an indefinable emotional content in the earlier music may be rooted in the fact these artists were the trailblazers, the ones who ascended out of a time of virulent racism. And maybe this is the edge I hear in their music that keeps me going back for more.”

Edward Brown and Annie Caldwell prefer a simpler explanation for the appeal of their music. “Times can be hard but you mustn’t forget that God is good,” he says.

And they’re making the most of this moment. “I’m going to close my clothes shop in Aberdeen for a few days,” Caldwell says of their forthcoming London performance, “and have me a vacation!”