“Cities are really palimpsests, so [Edward] Hopper’s New York is definitely still here. You may need to look around for it, but I like that sense of discovery.”

Kim Conaty, the Steven and Ann Ames Curator of drawings and prints at the Whitney Museum, has spent the past four years working on the museum’s latest Hopper show. It’s the Whitney’s first Hopper exhibition in a decade, since 2013’s Hopper Drawing, which focused on this drawings. That’s a long time, considering that the Whitney holds the world’s largest collection of Hopper’s work.

The new show, Edward Hopper’s New York, presents the famed American realist as a tried-and-true New Yorker – one who both captured unique, overlooked aspects of his city while also finding ways of universalizing it. Running until March 2023, it’s a large show, with more than 200 paintings, watercolors, prints, and drawings, and it’s the first show ever to focus on Hopper’s life in the Big Apple.

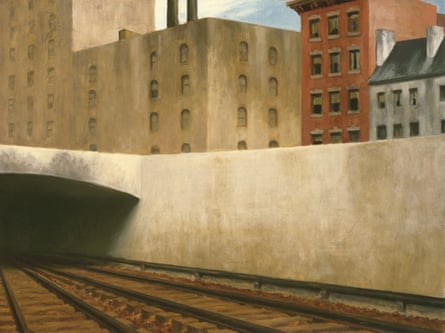

Born in upstate New York’s Hudson River Valley, Hopper moved to New York City in 1908 and spent the majority of his life there until his death in 1967. As a painter he eschewed statements like New York’s world-famous skyline and the Brooklyn Bridge in favor of more overlooked vistas that brought the endless expanses of steel and concrete down to a human scale. This can be seen in works like Approaching a City, which shows a sight familiar to countless New Yorkers: a stretch of commuter rail just before it disappears into a tunnel. “That particular underpass is, for many people, a first encounter with the city,” said Conaty. “There’s that moment he captures, that exciting, anxious, thrilling moment just before the unknown. It reminds me of my first trips into the city and all of the butterflies, the palpable excitement.”

The exhibition emerges from the painter’s long and storied relationship with the Whitney, which goes back to 1920, when the Whitney Studio Club hosted his first solo exhibition. Throughout the years Hopper remained a major presence at the Whitney, taking part in 30 of the museum’s biennials and annuals, including its very first one in 1932. “When I think of Hopper at that first biennial, I love the idea of how the historic was contemporary once,” said Conaty.

The relationship between Hopper and the Whitney took on a new significance after Hopper passed, when in 1970 the holdings of his studio went into the museum’s possession. “It was 3,000 works, which was doubling the Whitney’s entire collection at the time,” said Conaty. “That’s always a staggering thing to think about, how at that moment Hopper was half of the Whitney’s collection.”

Conaty and her colleagues have thoughtfully mined the Whitney’s storehouse of treasures while also utilizing loaned works to create a look at Hopper that feels both thoughtful and fresh. This large and diverse collection of paintings, sketches, illustrations, notebooks, and ephemera has been divided into various subsections, among them the artist’s many cityscapes, views of Hopper’s Washington Square neighborhood, the countless sketches he made while walking the city, and his very distilled late works. By arranging things in this way, Conaty’s goals is for audiences to find their own way through the exhibition, forging their own connections and conclusions.

“We thought a lot about the exhibition design of the show,” said Conaty, “a lot about it. We wanted to emulate that exploratory experience of moving around the city on your own. The open floor plan lets us underscore just how much Hopper returns to the same themes and motifs. We’re really hanging by theme and by feel, and I think that’s created a really different viewing experience.”

The show traces the roots of Hopper’s New York art back to his illustrations and etchings, where he first made his mark and where he honed an eye that would later be turned to making paintings of the city. It also points out Hopper’s enduring fascination with windows and theater scenes, grouping together numerous paintings on each of these motifs to powerful and stimulating effect “With the window paintings in particular,” said Conaty, “you’re immediately reminded of what it feels like as a pedestrian and as a resident, where public and private blends together because we’re all living in such close proximity together.”

The show includes many of Hopper’s late works, collected here under the grouping “Reality and Fantasy”. Showing solitary figures looking off into the distance, these works convey a sense of isolated longing, while seeming to take place in an anonymous anywhere. “Hopper has often been labeled as the quintessential American realist,” said Conaty, “and I don’t mean to diminish that he is giving us an essence of the city, but in these late works he’s really working so much more from his imagination and the collective imagination. He’s able to pull back and really distill, distill, distill, and give us an emblematic corner that could be New York or could be any city.”

The show succeeds at revealing a different side of Hopper, eschewing many of the artist’s most famous paintings in favor of ones that cultivate a sense of him as a New Yorker and an artistic innovator. In addition to helping audiences see anew an artist who has long been a fixture of the American imagination, it is also a show that will give tourists and longtime New Yorkers much reason to refresh their eyes and rediscover a city that they thought they knew.

“I like to imagine that when we New Yorkers see an artist reflecting on a city we know so well, it can remind you to see your New York,” said Conaty. “It can prompt you to walk out into the city streets and be curious about your New York, to be fascinated by a corner you walked by so many times and never took note of.”