Shared from www.theguardian.com.

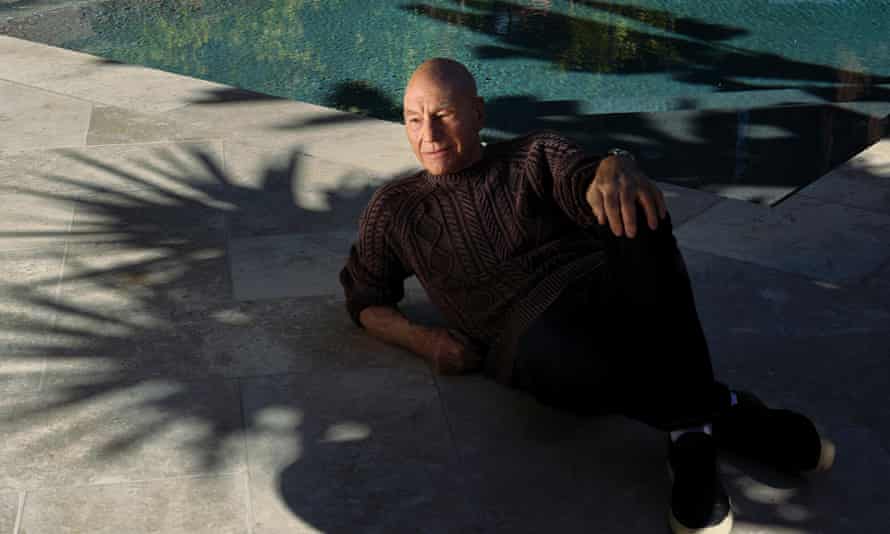

Patrick Stewart is slightly surprised to be talking about the impending second series of Star Trek: Picard, during a break from shooting the third in California. The reason is that he so firmly turned down the first season. After playing Captain Jean-Luc Picard, 24th-century hero of Starfleet, in 176 TV episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation and four spin-off movies, Stewart was convinced that “I’d done everything I could with Picard and Star Trek”.

But the producers – Akiva Goldsman (A Beautiful Mind), Michael Chabon (Wonder Boys), Kirsten Beyer (Star Trek: Discovery), Alex Kurtzman (The Mummy) – persisted. And Stewart “took a look at the names, and there were Academy award and Pulitzer prize winners. So I thought the most courteous thing to do would be to have a meeting to tell them face to face why I was going to turn them down.”

Over coffee, he explained his refusal: been there, done that, got the nylon polo neck tunics. But the petitioners asked if they could still make a pitch. They spoke for 20 minutes, Stewart recalls on Zoom from his Los Angeles home, after which he was intrigued enough to ask if they could send him something on paper. Reading those 36 pages “convinced me that there was enough new stuff to explore”.

Their clinching argument was that both the actor and his character had been in their 50s during The Next Generation, which ended in 1994; now they were octogenarian, with Picard retired from space and in exile, for reasons gradually clarified, at his family vineyard. The show would explore the intervening decades. “And when I looked at it like that,” says Stewart, “my attention was grabbed. Because they were doing the opposite of getting me to repeat what I’d done before. We would not be treading old ground just because that’s what a lot of people might like to see. It would be a new person with a different set of values and relationships.”

Did he watch old episodes or rely on his memories? “The latter. As the seven seasons of TNG went by, the distinction between Jean-Luc Picard and Patrick Stewart became thinner and thinner, until it was impossible for me to know where he left off and I began. So much of what I believed and felt went into that show. So coming back to the part, I felt that the impact of time on Jean-Luc would just be there in where I am now. And that’s how it has felt.”

Was the deal that if anyone played the older Picard, it would be Stewart – or was there a risk of switching on to find, say, his friend Ian McKellen in the part? “Oh, I would have watched that,” Stewart laughs. “What a clever idea. No. They were absolutely clear: if I passed on it, there would be no show. And I believed them and thought that was generous.”

As a classical stage actor – his focus before the Star Trek and the X-Men franchises gave his career a more lucrative second act – Stewart had twice played Prospero in The Tempest. Did the writers deliberately intend a parallel between the old, haunted astronaut of Star Trek: Picard and Shakespeare’s exiled Duke of Milan, brooding on a desert island? “Yes!” says Stewart. “That sense of the future lacking the significance it used to have. And a genuine fear that he doesn’t know how to handle things now.”

Filmed back-to-back due to confidence in the project, the second and third seasons “show much more of the romantic and emotional life of Picard, which there was very little of in the original series. There’s an increasing feeling that he missed out on an awful lot of living.”

But wasn’t Picard’s status as a sort of space-monk, ascetic and celibate, a deliberate contrast with predecessor William Shatner’s James Tiberius Kirk, who had a new date or old flame on every planet? “Yes, that’s true. That was a factor in The Next Generation. But by the time of the sequel, we felt able to explore whether Picard might be able to find a way of living alongside someone.”

McKellen – who achieved a similar late-career screen superstardom – has spoken of the shock experienced by actors who move from classical theatre to fantasy franchises, especially the intensity of the fans. Did Stewart also find the adjustment difficult? “It’s not that I found it difficult. I just initially refused to acknowledge it. Throughout the first season of The Next Generation, I was continually getting these invitations to attend something called ‘conventions’. And my reaction was no because that had nothing to do with what I was trying to achieve: I wanted the show to have an impact on screen, not me standing on a platform talking about it.

“But at the end of the season, I accepted one in Denver. They took me to the back of this big building and I said, ‘What if no one turns up?’ And they looked at me like I was talking gibberish. I walked out and there were more than 3,000 people in this vast auditorium. And it overwhelmed me – not just the enthusiasm for my being there but an intense sense of affection and respect. Which wasn’t something I’d always experienced in this profession. After that, I’d do three or four of these conventions in each season.”

The success of The Next Generation initially led Stewart to turn down the first X-Men movie in 2000. “I said, ‘Look, I know this isn’t science fiction but it’s fantasy, and I’ve done that.’ But they persuaded me that it wouldn’t be like Star Trek, so I did it. And yet again I was proved wrong. Both shows broadened my sense of what it was to be a professional actor. I’ve been an actor since I was 18 – and I’m now 81. I think the last 10 to 15 years have had more impact on me than anything before and left me more than ever compelled to do this job.”

That period included, in theatre, an acclaimed Macbeth, a Waiting for Godot in the West End and on Broadway, and then Harold Pinter’s No Man’s Land. Both the Beckett and the Pinter were as a double act with McKellen, who was also in the first X-Men film. Did he talk the reluctant Stewart into signing up? “No. This is the odd thing. Although I always admired Ian – an actor of that quality and passion, how could you not? – we didn’t really know each other well then.”

At the RSC, they tended to be playing the lead in different shows. “It’s only in the last couple of decades that we’ve become like brothers. It was due to X-Men, in fact. I’ve always been quite a shy person. But we were shooting X-Men in Toronto and in adjoining trailers at the base camp. On that kind of technically complex film, you spend far more time sitting waiting to work than working. So we’d hang out together in his trailer or my trailer and it was the element that made me most grateful for X-Men: that it brought Ian into my life. Ian was already cast in Waiting for Godot as Estragon and was looking for a Vladimir, and he chose me. In both the Beckett and the Pinter, it helped that we are able to tune into each other very easily. Although actually, we are very different people. There are many differences and distinctions.”

Apart from McKellen having been a key gay rights campaigner and Stewart being married to a third wife, Sunny, the pair are also a theatrical War of the Roses: McKellen from Lancashire (Burnley), Stewart Yorkshire-born (Kirklees). The white-rose actor laughs: “Yes. Indeed. And there’s also what Ian calls my obsession with my poor education. He won a scholarship to go to Cambridge, and I left school at 15 and two days. I was at a secondary modern school, where a great English teacher first put Shakespeare into my hands and asked me to read it aloud. But I feel a sense of intimidation at Ian’s level of education. Although I now understand he spent most of his time at Cambridge acting rather than studying.”

Although both have played Prospero and Macbeth, Stewart’s move to the US in the 1980s means that two great Shakespearean roles graced by McKellen – Hamlet and King Lear – have eluded him. Stewart, though, points out that, as McKellen last year played Hamlet again at the age of 82, the Prince of Denmark may yet come his way. “When I heard Ian was doing that Hamlet with non-conventional casting,” says Stewart, “I asked him if I could play Ophelia because it felt absolutely natural. But the timings didn’t work out.”

Stewart has been talking to a director about the possibility of a King Lear on stage, for which he is the traditional generation and gender, although this show might also include some unusual casting. When I suggest that McKellen could play Lear’s Fool, Stewart says: “My feeling is that Ian would want to play Cordelia. I’d love to have him as my daughter. I’m just worried that stamina would be an issue. I’m not sure I could do eight shows a week as Lear; it would have to be six maximum, which may not suit producers. So it may be too late. But I feel I’d have missed out on an experience if I never play Lear.”

It is the energy and intensity of theatre that both attract and alarm him. His acclaimed Macbeth from 2007 to 2008 “ended on Broadway exactly 365 days after the first preview in Chichester. It was all I did for a year. I had difficult patches and there was a period when we were in New York that performing that play took everything I had. I would end the show emotionally exhausted, go straight home and drink alcohol until I passed out. I’d sleep for a good many hours and then find that, by about four in the afternoon, there were little stirrings of, ‘You’re going to play this great role again in a few hours.’ And I’d know it would end with me being fucked in a few hours. But it was the only way I could find to do it. And I think that year opened up new possibilities for me. Everything has to count; it’s not just fun any more.” But surely he couldn’t carry on with the burn-out-black-out-repeat of that Macbeth year? “No. I know now that I have to stop and take a break.”

The British TV section of his CV is sparse: I, Claudius, Smiley’s People, Maybury between 1976 and 1983, after which his screen work is almost all American. Could or should he have done more in the UK? “Possibly. I don’t think of them as being separate. Tomorrow, I’ll be picked up at 4.30 and taken to a Hollywood studio where I’ll be in front of cameras, which is what I’ve been doing for much of the last 40 years. But it doesn’t feel different from filming in Britain, or theatre. When the medium changes, acting still stays the same for me – which is to make it truthful.”

The nature of truthful acting has recently become disputed, with pressure for “authentic” representation rather than imaginative transformation. Stewart’s X-Men character, Professor Charles Xavier, uses a wheelchair. Some actors and commenters would now argue that an able-bodied actor should no longer play that part. What is Stewart’s view? “I think the argument, while coming from a very good place, is a resistance to creativity in the work that we do. I respect and understand the feelings but I think we would be denying people experiences and performances by saying, ‘No, no, no, it’s not appropriate you should do that.’”

The argument being that an actor can still achieve “truth” by pretending to something they have not experienced? “That’s absolutely spot on. Theatrical reality is a lot more complex than some people think. If the ‘authenticity’ rules had been in place for the last 100 years, we would have missed so many performances. I still want to explore everything as an actor.”

After shooting season three of Star Trek: Picard, he plans to take several months off to complete a memoir. He’s reached page 310 and it’s called Are You Anybody? The title has been percolating for decades. “On my first RSC opening night at Stratford-on-Avon, I was playing the Earl of somewhere in Henry IV, tiny part. There was a group of autograph-hunters at the stage door, and someone thrust the programme at me to sign, then pulled it away again and said, ‘Are you anybody?’ And I said, ‘No, nobody at all,’ and walked away. But the importance of that question has stayed with me ever since.”

Images and Article from www.theguardian.com