As a teenager, Veronika Megler was intent on becoming a statistician. She signed up for a computer science course at Melbourne University, reasoning it would assist her chosen career. “I think there were four women in a class of about 220 people, and it was pretty misogynistic,” she recalls. Megler had already built her own PC, buying the motherboard, chips, capacitors and diodes from an electronics shop in Melbourne. “In the store they’d say ‘tell your boyfriend we don’t have these’,” she recalls.

Realising that statistics wasn’t for her, Megler answered a newspaper advert for a part-time programming job at a local software company called Melbourne House. It was 1980, and she was halfway through a course that focused on designing operating systems and developing programming languages. “The day I was hired, the first thing my boss said to me was, ‘write the best adventure game ever,’” she remembers. The eventual result of this instruction was The Hobbit, a landmark 1982 text adventure game that’s still fondly remembered today.

Though the 20-year-old didn’t have a lot of experience with video games, she’d enjoyed one in particular. “I had found Colossal Cave Adventure addictive until the point where I had mapped out the game and solved it. Then it instantly became boring, and I never played it again. So I thought about what it was that made that game stop being interesting, and designed a game that didn’t have any of those issues.”

Megler enlisted fellow student Phillip Mitchell to assist with the game’s parser – the code that helps the game and the player to understand each other, turning words into commands and vice versa. The story was originally a generic fantasy adventure. However, as fans of Tolkien’s work, Megler and Mitchell suggested using one of his works as a base for the game. The sprawling and epic The Lord of the Rings stories were the most famous; the programmers suggested that the less complex and tighter plot of The Hobbit would be a better fit.

Melbourne House boss Fred Milgrom loved the idea, and Megler began adapting the book. “I went through it and identified key locations, characters, puzzles and events,” she says. “Then I tried to map that into the game. It seemed doable. But it was a stretch. And probably a little too ambitious.” By the time Melbourne House secured the Hobbit licence, Megler had already designed much of the game’s engine.

In most text adventures of the time, the player typed commands – examine sword, go north – and the program reacted accordingly with a set of preset replies. But writing code on a TRS-80 knock-off computer from Australian manufacturer Dick Smith Electronics, Megler created an innovative system that allowed the player to experiment with different commands and objects. “The classic example was ‘turn on lamp’. It turns on the lamp, right? But turn on the angry dwarf, and you turn him into a randy dwarf that continually propositions you,” laughs Megler. (Sadly, this particular interaction was removed from the final game.)

In an era where most text adventures could be boiled down to a game of “guess the correct verb”, The Hobbit allowed for adverbs and using items, eliminating the issues that had bugged her in Colossal Cave Adventure. The game also allowed for the passage of time: if you dawdled for too long in the wrong place, Bilbo soon became a juicy snack for a troll.

“I saw it as a super-interesting puzzle to solve – and I saw the possibility of what could be done – so I just did it,” says Megler. “There were essentially message templates and a dictionary of words, and a lot of the power of the game comes from the fact that there are just three or four basic ideas that interact with a fair amount of randomness to create what can be called emergent behaviour.” At a time when most home computer video games were still coded in Basic language, this was remarkably progressive work.

Megler had the foresight to structure her system so it could be scrubbed clean and used as the basis for more games. “I designed [The Hobbit] so that it would have pluggable parts: you could take the same basis for the game and then just change the character lists and map and sell it as a different game.” Sadly, apart from a followup based around Sherlock Holmes, Melbourne House failed to take advantage. It seemed the world was not ready for an adaptable game engine.

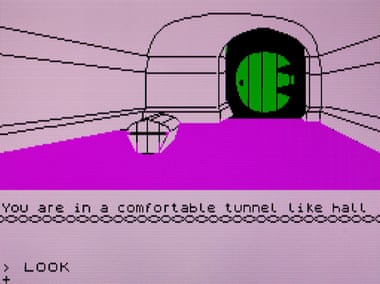

About halfway through writing The Hobbit, Megler and Mitchell were called away to work on another game called Penetrator – Melbourne House’s transparent knock-off of Konami’s seminal scrolling shoot-’em-up Scramble. They created an excellent clone with an innovative feature: a level designer. “After we’d written Penetrator, the idea came up of adding a graphical element to the Hobbit,” remembers Megler. Artist Kent Rees drew the famous images, which Mitchell expertly rendered into the game using a minimal amount of precious memory.

If there’s one thing that anybody who played The Hobbit in the 80s remembers with a smile – or a grimace – it’s that annoying dwarf-king in exile, and his enthusiastic singing. “One of the iconic things about Thorin in the book was that he frequently sat down and sang about gold,” grins Megler. “So, I picked that up as something that was quintessentially him … The problem with Thorin was that the sequence was too short! So he ended up sitting down and singing about gold much more than he did in the book.”

Released in the UK and Australia in 1982, The Hobbit accrued glowing reviews and awards in the press. The ambition, skill and determination of these two part-time students, charged with making the “best adventure game ever”, has influenced a whole generation of gamers and coders. “I think solving a problem within tight constraints – which is the space we were in – unleashes a very different type of creativity,” concludes Megler. “And that in itself can be very powerful.”

Why is it that The Hobbit made such an impression? Forty years on, why is it still talked about? “I think it’s because it was revolutionary compared to the other games available at the time,” muses Megler. “I mean, I’ve had letters from people who talked about how it’s changed their life; others who became interested in relationships and people rather than just shooting games. And people who have done PhDs in linguistics because they found the parser so fascinating.”