Elvis Presley was a global phenomenon. He had a larger than life persona that kept him in the headlines right up until his death. He churned out hit album after hit album. He put all the pelvic thrusting we take for granted now, on the map. His recordings generated insane amounts of money and continue to do so to this day. Between the mid-50s and his death in the late 70s, Elvis’ touring performances, Las Vegas’ show, record sales, and movie contracts, generated over a billion dollars in revenue. Unfortunately, like many artists before him, and many artists since, a few unscrupulous people who worked with him managed to bilk him out of millions. Here’s the story of how Elvis rose to incredible popularity, and how one man quietly pocketed the majority of his success.

Early Life

Elvis Presley was born in Tupelo, Mississippi on January 8, 1935. He grew up quite poor. His father worked odd jobs and spent time in jail for writing fraudulent checks. Elvis was very close to his mother and the two of them were often left alone while Elvis’ father went off to look for his next job. Elvis was first exposed to music at the Assembly of God church that he attended with his parents each week. He made his first public singing appearance when he was in first grade, as part of a talent show at the local fair. He was subsequently given a guitar for his birthday. He learned to play moderately well over the next few years, and was given a chance to perform on his favorite local radio show when he was in sixth grade. After his family relocated to Memphis, Tennessee, he was discouraged from his interest in music by his high school music teacher. In fact, music was the only class he failed during his teenage years.

While his teacher was telling him he had no future in music, he was spending most of his time down on Beale Street, absorbing all the Blues that he could. He took to dressing like the performers he saw each evening, including growing out his sideburns and curling his hair using Vaseline and rosewater. His senior year, he performed at a popular local “minstrel” show. It made him an instant sensation among his classmates. He was heavily influenced by the African-American gospel groups of the time, and listened to multiple local musicians, including Arthur Crudup, B.B. King, and Rufus Thomas. Elvis knew he wanted to pursue a career in music, but he was unsure of how to start. In the summer of 1953, he went in to Sun Records, a Memphis-based recording studio and label that was known for its roster of popular African-American artists. He asked to buy some studio time to record two songs for his mother. He seemed unwilling, or unable, to describe the type of singer he was. When Sam Phillips, the head of Sun Records asked the receptionist, Marion Keisker, for his name, she wrote it, along with the note, “Good ballad singer. Hold”. With that, Elvis Presley found himself signed to Sun Records.

His first recordings for Sun were unsuccessful. They couldn’t seem to find the right musical vehicle for him. It wasn’t until late one night, while he was goofing around in the studio with two other musicians, that they found the Elvis sound. While listening to Elvis Presley jump around and play “That’s All Right” by Arthur Crudup, Sam Phillips realized he had a goldmine on his hands. He’d long been looking for a white musician to bring the “black” sound that was Sun’s hallmark to a wider audience. He realized he’d found him. Elvis’ cover of “That’s All Right” proved to be a hit on the radio, and when people began calling in, insisting that the singer was black, Elvis was interviewed and gave the name of his high school to prove that he was white. In the segregated south, everyone knew which schools were for which race.

Over the course of the next two years, Elvis would build a substantial regional following. He traded in his $8 guitar for a $175 one, and inked a deal with the show, “Louisiana Hayride“, to perform every Saturday night for a year. It was around this time that Elvis was introduced to music promoter, Colonel Tom Parker. Parker was known for being tenacious and fiercely protective of his artists. As Elvis’ popularity expanded, Parker and Elvis’ manager, Bob Neal, began to negotiate ever more lucrative contracts for him.

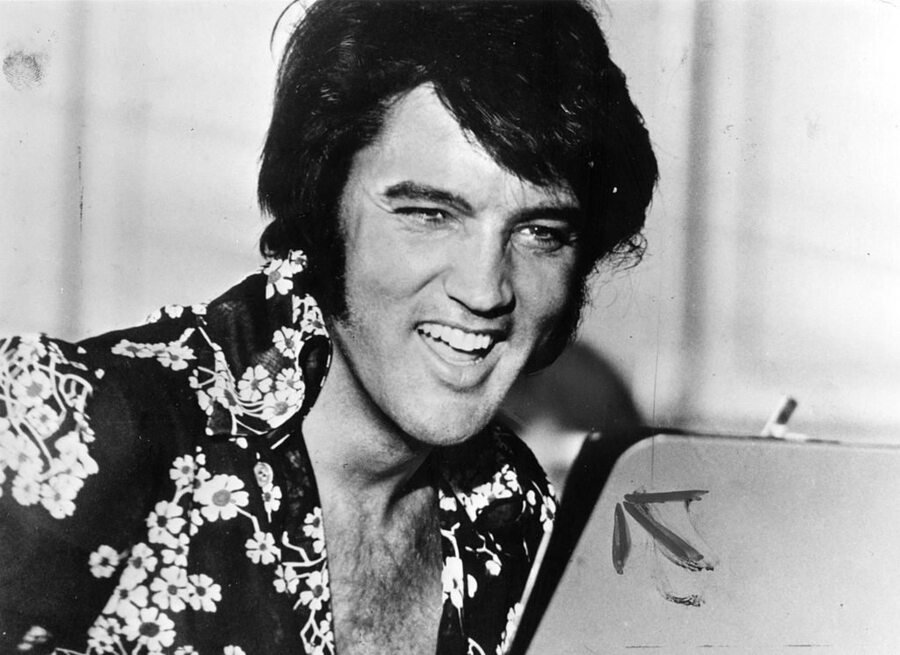

Elvis Presley / Keystone/Getty Images

Rise To Stardom

In November of 1953, RCA Victor bought Elvis’ contract from Sun Records for a then-unheard of $40,000. In 1955, that was a massive amount of money. Within a few months, Elvis was recording for RCA. Over the course of the next 20 years, he would go on to release 18 albums and have 32 #1 singles.

Elvis sold 600 million copies of his albums worldwide, and he won three Grammy Awards, from 14 nominations. He received the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award when he was only 36. Elvis also launched a moderately successful film career, which was interrupted by his two tours of duty in the military. His films such as, “Love Me Tender, “Jailhouse Rock”, and “Viva Las Vegas”, were huge hits at the box office, and spawned popular soundtrack albums, as well. With so much going right, you’d figure Elvis Presley would be rolling in dough. He wasn’t, however, and it turns out that was all due to one man – Colonel Tom Parker.

As any actor or musician with a manager/agent knows, it’s customary for your rep to take anywhere from 10% to 20% of what you earn per job that they find for you. If you are signed with an agent and a manager, you’ll be paying both their cuts before you get your paycheck. Colonel Tom Parker acted as Presley’s promoter and, then manager and promoter, for most of his career. Parker managed his career with an iron fist. Multiple successful musicians, Hollywood film producers, and television executives approached Elvis about work. However, they had to get through Parker first. If Parker didn’t think the price was right, he turned them away. Elvis was handpicked to star opposite Barbara Streisand in “A Star is Born“. Parker turned it down. Elvis was approached about appearing in “West Side Story“. Again, Parker turned the job down. Instead, he signed Elvis up for a series of formulaic low-budget movie musicals. Elvis sang the soundtracks for each film, and for nearly seven years, soundtrack albums were the only new music he released. On the surface, he seemed to be living the high-life, and when he launched a return to live performance in 1968 with his award-winning special, “Elvis”, it was clear he was poised to make even more money.

Less than a decade later, Elvis was dead. He continued to tour almost up until the day he died, but had had become overweight, paranoid, and increasingly incoherent, as an addiction to prescription pain killers ravaged his body and mind. Parker had reportedly done little to try to stop his client from self-destructing. Towards the end of Elvis’ life, neither man spoke to each other much, even thought Parker was still managing Elvis’ professional life.

Elvis’ Net Worth At Death

To much of the world’s utter shock, when Elvis died, he was only worth $5 million. And while that would be worth roughly $25 million after adjusting for inflation, how could THE KING not be worth hundreds of millions? Perhaps more! After all, Elvis was the first artist to pass the billion dollars in sales mark. So, where’d the other $990,000,000 go? You’d have to ask to Colonel Tom Parker.

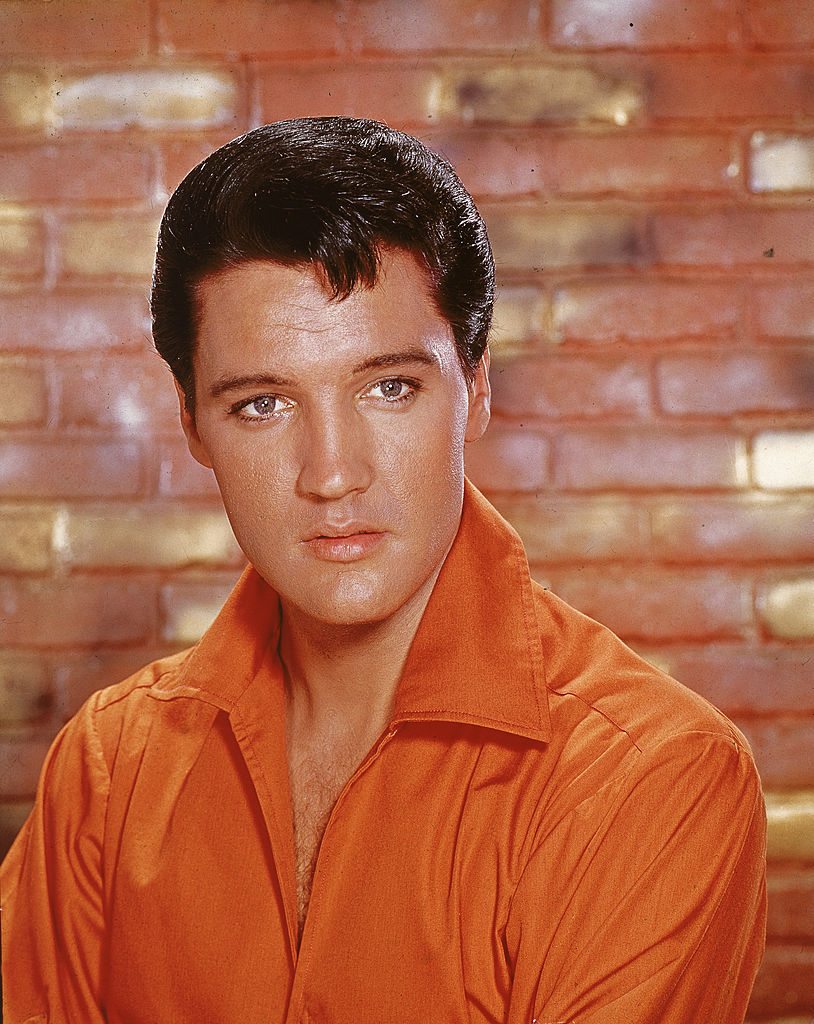

Elvis Presley / Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Where’d All The Money Go?

Elvis rarely read his contracts. He hated paperwork of that type. At the same time, Parker had a a habit of making the contracts whatever he needed them to be. At one point, he tried to get Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, Elvis’ primary songwriters at RCA, to sign a blank piece of paper with lines for their signatures on it. When asked “What kind of contract is this?” He responded, “There’s no mistake, boy, just sign it… we’ll fill it in later.” Leiber and Stoller chose to end their artistic relationship with Elvis at that point. By the time Elvis launched his late 60s comeback, Parker was receiving 50% of all of his earnings from recordings, film work, and any Elvis-related merchandise. In the early 70s, he expanded his contract to include receiving 50% of all of Elvis’ live performances. With the exception of three dates in Canada, Elvis never performed outside of the US. Parker insisted it was because the venues were too small, or the pay was too small, but it may have had more to do with the fact that Parker was unable to leave the country due to rumors about Parker’s alleged involvement in a murder in his home country of the Netherlands years earlier.

When negotiating royalties for Elvis’ albums, Parker negotiated a flat-rate royalty of 50 cents per record – for himself. It was a great deal for Parker, but a horrible one for Elvis. As record prices increased, Parker’s static cut made Elvis’ percentage of the royalties decrease. Parker also agreed to a ridiculously low sum of money for the masters to all of Elvis’ recordings. He charged just $5.4 million to sell off songs that had earned over a billion. He then split the $5.4 million with Elvis – 50/50. As Elvis’ popularity resurged in the late 60s, Parker began to produce more and more Elvis-related merchandise. However, he didn’t share the stock in their manufacturing company, Boxcar Enterprises, with Elvis equally. Instead, he got 40% and Elvis got 15%. By the late 70s, he owned 56% of Boxcar, and Elvis’ estate owned only 22%.

A trial was conducted in 1980 regarding the mismanagement of Elvis’ earnings. While Elvis clearly signed all of the various and sundry contracts Parker passed his way over their decades long association, the question arose as to whether Parker ever had his client’s best interests at heart. Even after Elvis’ death, Parker was still receiving 50% of all sales related to the artist. This was a lot of money, since Elvis continued to have successful posthumous record sales. He still remains one of music’s most popular artists. This meant that there was less and less coming to his estate and sole heir, Lisa Marie Presley. Blanchard E. Tual, an attorney, was appointed by Judge Joseph Evans, to look more deeply into Elvis’ financials. Tual found a mess of mismanagement, backhand deals, and missed opportunities. Parker had advised Presley to turn down the opportunity to sign up with ASCAP or BMI. This meant that Elvis never received any royalties on any of the songs he’d co-written. Parker turned down multiple, massive, European tours. Turns out he didn’t want anyone finding out that he wasn’t from the US. He was actually from the Netherlands. After Parker was sued for mismanagement, he countersued. Three years after the initial trial, a settlement was reached. The Presley estate paid Parker $2 million and he was not allowed to receive any money from anything Presley-related for five years. He also had to give any recordings, pictures, or other Elvis’ related memorabilia, back to the Presley family.

After regaining control of Presley’s assets, Elvis’ heirs moved quickly to secure and capitalize on the singer’s image. By the early 2000’s, Elvis had become the highest earning dead celebrity in the world. In 2004, the Elvis estate earned over $40 million. In 2005, Lisa Marie Presley sold an 85% stake in her father’s image to an entertainment licensing firm called Core Media Group for $115 million.

Parker was still living in the same hotel suite in Las Vegas that he’d been living in at the end of Elvis’ life, but he was subsequently evicted. His gambling debts were so high that he couldn’t afford to live there anymore, even with the $2 million he’d been granted by the court. At the time of Parker’s death, he was worth less than $1 million, and owed the Las Vegas Hilton Hotel $30 million. At one time, he’d been worth over $100 million (equal to hundreds of millions in today’s dollars). Turns out, his mismanagement of funds extended to his own bank account, as well.

The story of Elvis’ association with Colonel Tom Parker is a cautionary tale for all artists. If the person helping you get work is taking more of a cut than you, sever ties. If the person managing you is making decisions that seem to squash your career, rather than expanding it, drop them. Most importantly, if your manager or agent hands you a blank contract and says, “We’ll fill it in later”, for pity’s sake, don’t sign it. Your art is your legacy. Make sure you get paid for it.