Shared from www.latimes.com

Tom Holland’s follow-up to “Spider-Man: No Way Home”: a starring role in “Uncharted,” based on the blockbuster video game created by Naughty Dog.

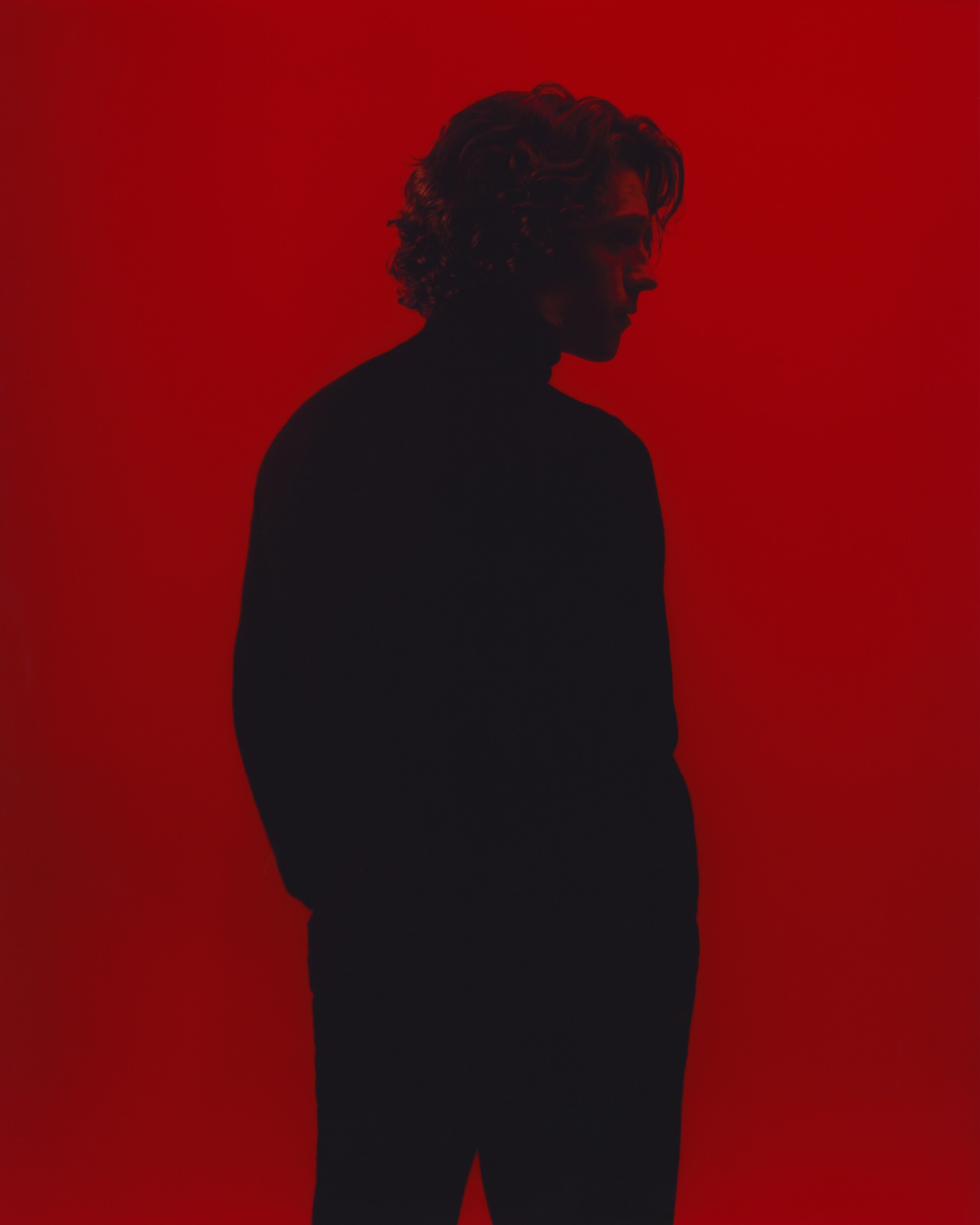

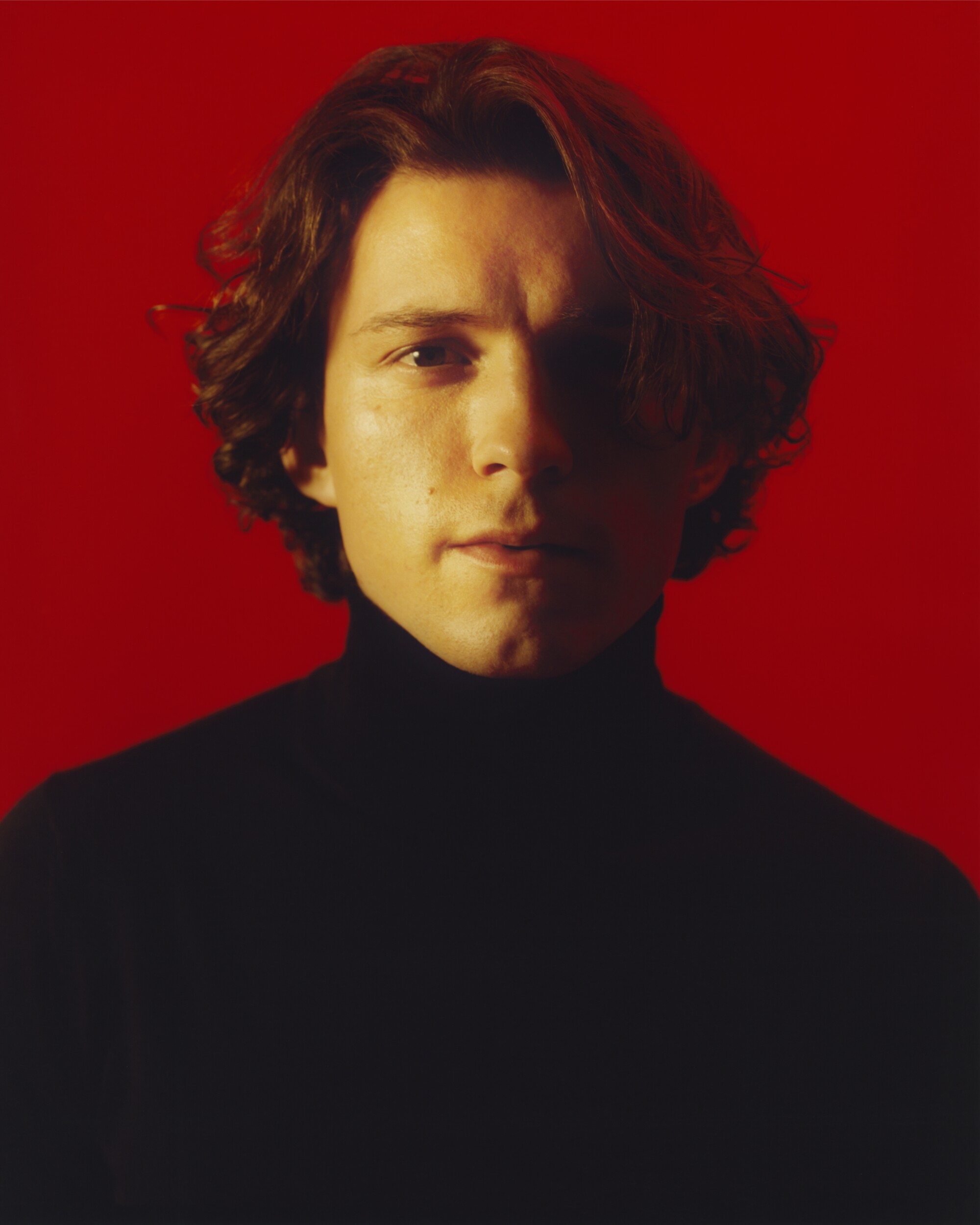

(Charlie Gates / For The Times)

If “Uncharted,” mired in development delays for the better part of a decade, becomes a global film franchise for Sony Pictures, the love Tom Holland has for the PlayStation video game console will become the stuff of legend.

It was on the PlayStation, between takes on 2017’s “Spider-Man: Homecoming,” that Holland immersed himself in the world of “Uncharted” — and accelerated his desire to portray a globe-trotting adventurer such as Indiana Jones or James Bond. “Uncharted” even led him to try his hand at pitching a Bond story.

But more on that in a moment.

Before video game studio Naughty Dog was known for its linear, story-driven narratives “Uncharted” and “The Last of Us,” two properties being adapted for film and television, it was a production house home to more lighthearted fare, particularly the run-and-jump series “Jak and Daxter.” Holland cites “Jak and Daxter” as one of his first video game crushes and talks about meeting Naughty Dog’s Neil Druckmann the way other actors gush over meeting a legendary director.

“He actually worked on ‘Jak and Daxter,’ which is one of my favorite games. I loved that game as a kid,” Holland says of Druckmann, who started as an intern at Naughty Dog and worked as a programmer, designer, writer, creative director and vice president at the Santa Monica studio before he was promoted to co-president in 2020.

“We were big gamers as kids,” Holland says of himself and his three brothers. “Our parents were always quite strict. We weren’t allowed to play video games on a school night. So I do remember waking up early on a Saturday morning trying to beat my brothers downstairs so I could get to the PlayStation first.”

In the movie version of “Uncharted,” Nathan Drake, portrayed by Tom Holland, right, is missing the father figure of his older brother and finds a thief-going partner in Mark Wahlberg’s Victor “Sully” Sullivan, left.

(Clay Enos / Columbia Pictures)

In 2022, video games appear to be the next big intellectual property arena for movie studios and streaming services. “Uncharted” comes shortly after L.A. studio Riot Games had a hit with Netflix’s adult animation series “Arcane,” weeks before a “Sonic the Hedgehog” sequel and “Halo” series for Paramount+, and months before HBO, with Druckmann’s heavy involvement, launches a series based on the somber, traumatic, zombie-inspired game “The Last of Us.”

“It’s a testimony to how good the video game IP is and how robust it is in terms of narrative,” says Atlas Entertainment’s Alex Gartner, one of the producers on “Uncharted.” “It’s robust in terms of narrative, and it’s matured. It has created real characters. It’s not just the playability of the games anymore. It’s the characters.”

For “Uncharted,” that main character is Nathan Drake, originally inspired for the game by “Jackass’” Johnny Knoxville and portrayed in the film by Holland, about a decade or so younger than the character seen in the series’ first 2007 installment. Drake, as written in the games, was a serious-yet-carefree persona who made his living, such as it was, as a not-always-successful thief.

Drake’s story arc came to a conclusion in the games with 2016’s “Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End”; a non-Drake-starring spinoff was issued a year later. In the film, due in theaters Feb. 18, audiences will be introduced to a Nathan Drake with a borderline pathological desire for life-threatening adventures, this time following in the sailing path of Ferdinand Magellan in an attempt to find a hidden treasure as well as discover what happened to his long-lost brother, Sam.

“The core narrative vision for this game was trying to deal with someone who has an addiction to this,” Druckmann says. “He needs this in his life, to the point he doesn’t even realize. What if you oversteered with your life and try to find balance and the right relationship and move away from all that, to the point that you hurt who you are? There’s a calling you’re not answering. The narrative question is: Can you ever find a balance? That very much parallels our lives. We dedicate too much of our lives to our art.”

It was on the PlayStation, between takes on 2017’s “Spider-Man: Homecoming,” that Holland immersed himself in the world of “Uncharted.”

(Charlie Gates / For The Times)

Holland wasn’t the first actor attached to “Uncharted,” which has been in development for about 10 years. His desire to play the character, however, awakened his own yearning to see the world.

“I didn’t know there was a film in the works, but I did inquire about it with my agents,” Holland says. “They were under the impression that Ryan Reynolds was going to play Nathan Drake. For whatever reason that film was never made.”

Inspired by the game but thinking Drake was spoken for, Holland, in a conversation with Sony Pictures Chairman Tom Rothman, instead offered a pitch for a new Bond film, a franchise once in the Sony family.

“It was actually a really good pitch,” Holland says with mischievous insistence. “But I think from a marketing point of view it didn’t work. The idea of the film was you wouldn’t know he was James Bond until the end. He was supposed to just be a kid who was graduating into the SAS and goes on a mission, which is obviously exciting and adventurous. At the end of the film, he would be recruited into MI:6 and given the status of double-O and the title of James Bond. I thought it was really cool, but no one else, I guess, thought it was cool.”

Asked specifically what drew him to Drake, Holland is blunt and isn’t afraid to say there was a hint of selfishness motivating his push to get this film made.

“What intrigued me most about the character was his sense of adventure and where that would take me,” Holland says. “We’re talking about a character that explores the world and I love traveling, so I’m hoping that with this film series of ‘Uncharted’ we can go to places I would never have normally gone. So far that has been the case.”

If only everything could be so simple. Although “Uncharted” follows in a lineage of classic adventure films, from the “Indiana Jones” flicks of Holland’s youth to last summer’s “Jungle Cruise,” “Uncharted” the game was never a sure sell.

Sully and Nathan Drake in the game “Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End,” recently reissued for the PlayStation 5.

(Naughty Dog / Sony Santa Monica)

‘We actually had people leave the studio’

To understand the effect of the “Uncharted” games, one must capture the video game scene in 2007. With the risk of oversimplification, games that featured male protagonists — that is, most of them — tended to be of the brooding, tough-guy type. And if they didn’t, they were still often set in sci-fi-inspired locales.

An old-fashioned adventure of the Indiana Jones sort hadn’t really be seen since the “Pitfall” games of yore or the point-and-click of “Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis” in the early 1990s. Although plenty of video game liberties are taken with “Uncharted,” there simply weren’t many big-budget action games starring mostly normal people and set in what could be the present-day real world.

It was such a rarity that people quit.

“We actually had people leave the studio,” says Bruce Straley, who co-directed “Uncharted 4″ with Druckmann and, with “Uncharted” architect Amy Hennig, had a role in the early development of the franchise.

Straley, who left Naughty Dog, partially due to burnout, shortly after the release of “Uncharted 4,” explains that some Naughty Dog staff “were so adamant about losing the characterization and fun in video games that we had in ‘Jak and Daxter’ that they were appalled we would use motion capture. It would ‘restrict them as animators and creators.’ OK. It was that grounded of a game, but it’s not grounded at all, compared to ‘The Last of Us’ or more games that have come out.”

Holland’s desire for the project to get made is credited as the reason Drake is younger in the film than in the games, where the character is in his 30s and 40s. But Holland does capture Drake’s jovial approach to life; he’s a man who seems to revel in the ridiculous situations he gets himself into, even as there’s a part of him that longs for deeper connection.

In “Uncharted 4,” recently reissued for the PlayStation 5, the game plays with Drake’s struggle to settle down and be an honest partner to his wife. In the film, which largely side-steps romance, Holland’s Drake is missing the father figure of his older brother and finds a thief-going partner, eventually, in Mark Wahlberg’s Victor “Sully” Sullivan.

But he’s still ultimately a criminal. Holland says a lot of care was taken to make sure audiences connect with Drake in the film, especially since one of the first major set pieces is Holland, as a bartender, robbing a female customer.

“We needed Nathan to be very likable in this film, which is why we introduced the idea that finding the gold would mean finding his brother,” Holland says.

“What intrigued me most … was his sense of adventure and where that would take me”: Tom Holland on playing “Uncharted’s” protagonist Nathan Drake.

(Charlie Gates / For The Times)

“We wanted it to be the story of a young boy searching for his family and, in turn, finding a family in Sully. But, yeah, it was definitely something we spoke about. The scene where he steals that bracelet from the girl in the bar, we set up that she’s not the most likable person. She’s slightly rude to him. I think I even have a line — I say, ‘Would you like to keep a tab open? Of course you do. It’s daddy’s money.’ So stealing her bracelet doesn’t seem that bad. Not that anyone should steal anything from anyone.”

Besides, America has a thing for troublemakers. Indiana Jones was one, as was the original inspiration for Drake.

“There was something about Johnny Knoxville,” Straley says. “He was probably in his early to mid-30s at that point. He had a little bit of a nasolabial fold, that thing that represents age, but he still had a real lightheartedness in the way he laughed at himself. The fact that he could get hit by a car and roll with it and stand up and keep going was something we felt was interesting as a character. It’s the don’t-take-yourself-too-seriously nature. We knew there was something in there that was a creating a veneer, like, ‘I’m willing to risk my life and do these adventures.’ So it was interesting to examine Johnny Knoxville as a sketch of a character.”

‘It’s unclear how one should adapt’

The original “Uncharted” is a game meant to be a movie you can play. Is something lost if a game becomes a movie you can … watch?

After all, one of the film’s primary action scenes comes straight from “Uncharted 3,” a midair jump-and-fight segment amid cargo trailing an airplane. It’s unlikely any human would survive such a moment. In the game it works, as we’re in control of the character and see only the exaggerated action for the absurdly embellished set piece that it is.

“The joke in the industry was that nobody would survive a Nathan Drake jump,” Straley says. “You would literally drop down from any ledge and break a hip and that would be the end of your adventure. But we’re jumping on the sides of trains and grabbing them by the fingernail.”

“Uncharted” director Ruben Fleischer says he had to be cognizant of how far he could push his characters. What feels real in a game can look downright goofy when actual humans are doing the stunts.

Tom Holland with Sophia Taylor Ali in “Uncharted.”

(Clay Enos / Columbia Pictures)

“The scope and scale of the action is beyond anything on the big screen, and to try and make a passive viewing experience that can compete with that feeling of playing the character and being the character and being in the game is a fool’s errand,” Fleisher says. “You have to make a movie that works as a movie, that pays tribute to the source material but exists as a conventional feature film. But it isn’t trying to bring the video game from the PlayStation to the big screen.”

Ultimately, “Uncharted” serves as a prequel to the games, dialing back Drake’s age, keeping him single and not putting a gun in his hands until late in the film. That’s a different track than Naughty Dog is taking with “The Last of Us,” a series in development for HBO that is believed to more closely hew to the source material.

Druckmann and Straley have long talked up the cinematic influences on the interactive text for “The Last of Us,” including “No Country for Old Men” and the film adaption of Cormac McCarthy’s “The Road.” But while dealing with a flesh-destroying infection that turns humans into zombie-like creatures, “The Last of Us” takes pains to be rooted in reality, focusing on the trauma of such a situation rather than simply emphasizing the “fun” of shooting a monster. Its core is the story of a would-be father-daughter relationship, and where personal and societal sacrifices meet and conflict.

“I’ve been thinking about this a lot because there are two different approaches you can take,” Druckmann says. “The games, both ‘Uncharted and ‘Last of Us,’ are so cinematic. They’re scored. They’re acted. It’s unclear how one should adapt them — what to keep and not keep. With ‘Uncharted’ and ‘Last of Us,’ we’re taking very different approaches. With ‘Uncharted,’ it’s telling a whole other story that’s picking and choosing moments from the franchise and giving you an ‘Uncharted’ flavor.

One of Tom Holland’s first video game crushes was the Naughty Dog game “Jak and Daxter.”

(Charlie Gates / For The Times)

“With ‘The Last of Us,’ we’re trying to tell the same story that’s in the game, deviating in minor ways,” Druckmann continues. “I don’t know if either is wrong or right, but you have to play to the strengths of the medium. Here’s an experience that worked well, and you’re taking something out of it that is fundamental to telling its story, which is the interactive part. So you better complement it in other ways. For example, you can jump around between character perspectives in a way you wouldn’t in a game, because we’re trying to immerse you as the character you’re playing as.”

Druckmann, who has directed an episode of “The Last of Us,” says the influence of film and television on games will only continue and vice versa. That’s expected, especially as society leans more toward participatory types of entertainment, be it games, TikTok or the way gaming community Discord has continued to infiltrate mainstream communication. Druckmann says his approach to game directing will be informed by his time on the set of “The Last of Us.”

“I had the privilege of directing an episode for the HBO show, and it’s just learning how they handle cinematography or how they plan shots. So there’s a creative side to that — just how you’re thinking about clarity of storytelling. In this instance, each shot has to have a single purpose. You’re not trying to get muddy with too many ideas in one shot. It reflects a lot of our thinking in how we’re approaching games. But it’s just reinforcing the notion of clarity.”

Holland is just happy games are being taken seriously as IP. While making the media rounds for “Uncharted,” Holland has even expressed a desire to some interviewers to make a live action “Jak and Daxter” film. Turns out that time in front of a screen as a kid is paying off.

“I recently just bought the Oculus Rift and was using that, which is pretty cool,” Holland says of the Meta-owned virtual reality headset. “I love how when we were kids our parents used to tell us, ‘Don’t sit too close to the TV or your eyes will go square.’ And now kids are like, ‘Shove these screens in your eyes! It’s really cool.”

It’s also evidence that the video game generation has arrived.

Images and Article from www.latimes.com