There can’t be many people having more fun in their job than Alan Cumming. Whether it’s giggling his way around Scotland in a camper van with an outrageously rude Miriam Margolyes for Channel 4, sending up musicals in the gleeful song’n’dance parody Schmigadoon! or doing cabaret at his own bar Club Cumming in Manhattan, the phrase he repeats most often when talking about his various projects is: “It was a hoot!”

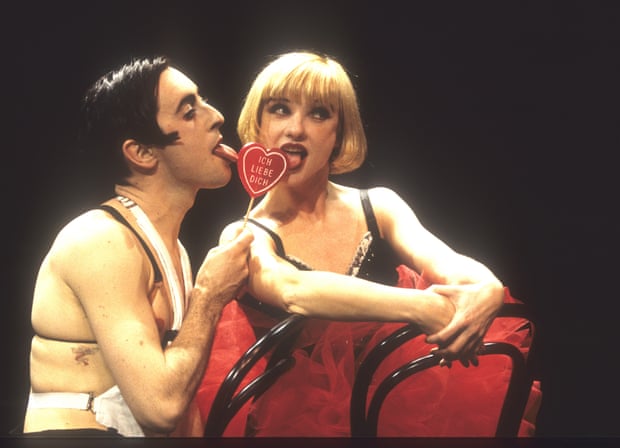

His latest memoir, Baggage, recounts hedonism aplenty, unexpectedly becoming the toast of New York as the emcee in the musical Cabaret on Broadway in the 90s. But that book came after a much more sober and surprising 2014 memoir, Not My Father’s Son, recounting the abusive behaviour of his father during his childhood in Angus, Scotland. The disconnect between a person’s public persona and the fuller story of their life is one that fascinates Cumming and it’s the trigger for his latest one-man show, Burn, based on the life of poet Robert Burns, premiering at the Edinburgh international festival.

In popular imagination we think of Burns as “romping in the hay and ploughing, and ‘Oh, here’s a poem!’” says Cumming. But the actor had “inklings” there was more to Burns than that. “And actually I think he was quite a tortured soul.” In writing his own autobiographies, Cumming thinks he’s changed his particular narrative – he is not only the boyish pansexual performer in circular specs with a mischievous grin that glints at me over Zoom, but also a man with a complicated past and a commitment to emotional frankness. He wanted to do some of the same for Burns, to undermine the sentimentality, the inclination “to biscuit-tin” him, as Cumming puts it. “To make someone into this figure that doesn’t reveal their wholeness and hides any chance of finding out the real person.”

A lover of drink and women, Burns had numerous affairs and illegitimate children while married to Jean Armour. “I was initially drawn to him when thinking about desire,” says Cumming. “How we have to constantly battle with having the life that we want and controlling our desires. I thought it was interesting the way he lived his life: his sexuality and promiscuity and the mess he made.

“He was a rock star,” Cumming adds, “but a rock star who had a huge hit – his first book of poems was massive – and then the difficult second album.” After success in his 20s, Burns dedicated himself to collecting and arranging folk songs and burned through his earnings, taking up a job as an excise officer to make a living, then dying in poor health at the age of 37.

It was a tumultuous life, and delving into it brought plenty of surprises for Cumming. Discovering, for example, that his letters weren’t written in Scots like his poems. “Writing in Scots was a choice for him, like the Proclaimers coming along and singing in Scottish accents, it’s radical and amazing.” And finding out that it’s generally agreed Burns was bipolar. “It’s not a controversial thing any more in academic circles to say that,” says Cumming. “There are surveys where you can see the manic phases in both his output and his libido, and records of doctors’ visits and depressive times. He has this energy schism going on in his life.” Burns’s spirit may now preside over merry celebrations of haggis and Hogmanay, but having pored over his letters Cumming couldn’t help but ask: was he happy? “He never seems joyous,” says Cumming. “I don’t think he was as happy as we’d all like him to be, and that was a shock.”

All these themes and more will weave their way into Burn, and just as the research offered up the unexpected for Cumming, the show itself comes in a surprising form, as a dance theatre piece. There’s some film, some text, but it’s mostly movement. “I’m 57, it’s not the time to be doing your first solo dance piece!” he chuckles at himself. But this is Cumming getting in touch with his true self. “I’ve always slightly regretted that I’m not a dancer,” he says.

Cumming has danced on stage before, of course, and the roots of Burn go right back to Cabaret, when he reprised his award-winning role in 2014. “I was 50 and I remember thinking: I’m never going to be this fit again, dancer-fit. I felt sad that something I’d really enjoyed was over. And then I thought, maybe I’ve got one more thing in me, and I put that out into the universe, thinking it might be another musical, or I might dance a bit in a play. I didn’t expect this.”

The universe answered him – or rather Cumming’s network of friends, producers, choreographers, directors and festivals nudged the idea along, including movement director Steven Hoggett, with whom he’d worked on The Bacchae for National Theatre of Scotland. At some point the dance idea collided with his “inklings” about Burns and the two combined to become Burn, Hoggett co-creating with another choreographer, Vicki Manderson, and featuring music by Anna Meredith.

Making the show is definitely pushing Cumming physically. “The last workshop, I was exhausted,” he says. “I had to go home and lie in baths of various salts.” He had to switch his digs because one place he was staying had no bath for his aching body. (He lives ordinarily in New York, with illustrator husband Grant Shaffer, although you get the sense there’s not much “ordinary” in his hectic schedule.) But he’s delighted to be dancing. “I tell stories with writing, I use my face in my acting, but to tell it completely with your body is a great thing,” he says. “And I don’t think it necessarily ends when your body isn’t capable of doing everything it could do.”

By which he means, bodies beyond their 20s and 30s have something to offer too. “I love seeing older people dance and move.” Cumming also loves how dance can make you loosen your grip on linear storytelling. “You’re forced into letting things go, the normal way you interpret narrative.”

Here’s a fact: Cumming actually made his dance debut in Matthew Bourne’s Swan Lake – the famous gender-switched version where all the swans were danced by men – playing one of the autograph hunters. He shared a flat with Bourne and hung out with the dancers. “I knew a few swans intimately,” he says with a little dreamy smile. “That was magical.”

He has a few dance people in his circle, including Mikhail Baryshnikov (whom Cumming says is “hilarious”, telling a tale about surprising the ballet legend in a dressing room wearing some indecently tight shorts that “needed to be pixelated”). A protege of Baryshnikov’s, Aszure Barton, choreographed Cumming in The Threepenny Opera. “She said, ‘Oh, I want to choreograph something for you and Misha’ but I was too shy.” He felt he wasn’t enough of a dancer, but now thinks the strict expectation that a dancer is someone with a particular technique and physique only stymies the art form. “In other art forms you are allowed to be raw and real and to tell your own story and I think dance has been remiss in that and basically says: these are the confines, you have to be able to do these things, otherwise your story’s not valid here.”

Cumming laughs in the face of boundaries generally, as he continues his omnivorous career. There’s a role in the new Marlowe film starring Liam Neeson as the private detective; there’s a second series of Schmigadoon! that he’s filming in Vancouver when we speak, spoofing the musicals of the 60s and 70s; and there’s another jaunt with Margolyes, extending the tour from Scotland to California. Having known each other a little, the idea to pair up came after being on the Graham Norton show together and they’ve since become close chums.

“We leave little WhatsApps for each other all the time, you’d be shocked by some of them,” he laughs. “There’s zero filter. She’ll say, ‘Darling, now I’m sitting on the loo so if there’s strange noises you’ll know what it is.’” Filming with Margolyes is like a Carry On movie, he says. “She always manages to top me in the naughtiness.” It’s a motley mix of projects that keeps him happy, and feeds all the aspects of a multifaceted performer. “I want to do good work, I want to do interesting things that challenge me,” he says. “But I do want to have fun.”