Shared from www.latimes.com

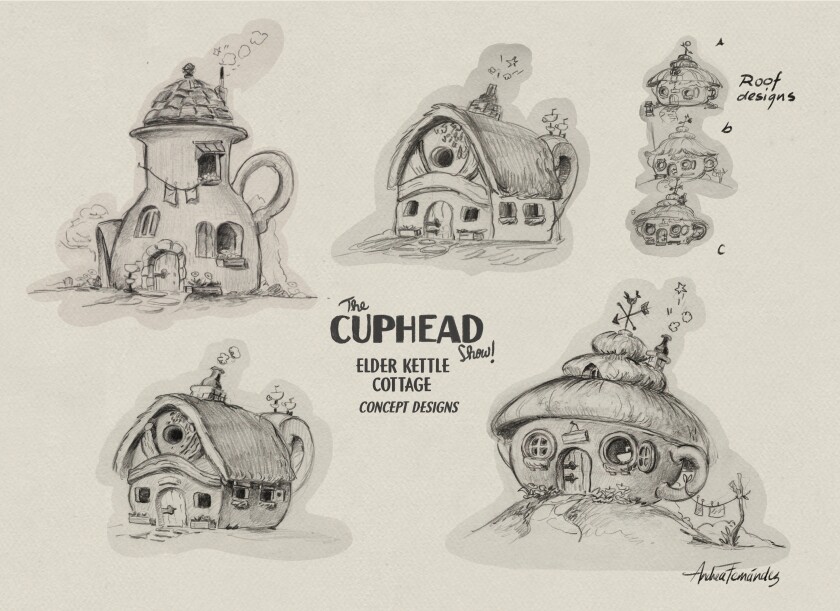

The opening shot of “The Cuphead Show!” is of a teapot-shaped cottage in the woods. Just outside the cottage are a goat and flowers dancing along to the upbeat background music. A couple of butterflies flutter by.

The brief scene-setter is notable because it involves 2D animation tracked over a 3D-sculpted miniature background, in what is known as the stereoscopic rotary process.

“It’s something that’s been dormant for decades, and to get to do things like that as somebody who works in animation [now], we savor every moment of it,” said “The Cuphead Show!” art director Andrea Fernandez.

“It’s painstaking and it’s expensive; that’s why it’s not done anymore,” explained executive producer Dave Wasson, who developed the Netflix animated series. “But it’s such a signature of those 1930s cartoons. The Fleischers invented this process. [We said], ‘If we’re doing a 1930s show, it has to have that.’”

“The Cuphead Show!” visual development by Andrea Fernandez.

(Andrea Fernandez / “The Cuphead Show!”)

Debuting Friday on Netflix, “The Cuphead Show!” is based on the hit 2017 run-and-gun video game “Cuphead.” Created by brothers Chad and Jared Moldenhauer of Studio MDHR, the fast-based action game is known for its difficulty as well as its cast of characters and its vintage cartoon looks.

The animated series follows brothers Cuphead and Mugman — the playable characters of the original game, named for the drinkware that make up their heads — and their adventures on the Inkwell Isles. Besides utilizing stereoscopic animation, the series draws upon the touchstones of 1930s cartoons and has adapted them for both modern audiences and the current TV animation pipeline.

The original “Cuphead” game was born of the brothers’ love for the surreal and experimental hand-drawn cartoons of the 1930s, including Walt Disney Productions’ “Silly Symphonies” and the works of Fleischer Studios. The animated adaptation — for which both Moldenhauers serve as executive producers — marks a full-circle journey in the medium that inspired them.

“‘The Skeleton Dance’ by Disney has been burned into my mind from a very young age,” said Chad Moldenhauer. “We rewatched that a ton throughout our life. The Fleischer series, all of this stuff, we found it so incredible. Back in that era of animation, they didn’t quite understand the subtle nature of acting, which is a benefit because [the animations are] wild and all over the place. We were always drawn to it — something about it just had that extra sparkle.”

Jared Moldenhauer credits the brothers’ affinity for these vintage cartoons to grocery store bargain bins that made them accessible in the form of VHS tapes.

“We ended up having a small handful of ‘Silly Symphonies’ and old Fleischer and ComiColor cartoons, which just stuck with us more than … ‘He-Man’ or ‘Ninja Turtles,’” he said. “We just found ourselves always coming back to these old tapes we had.”

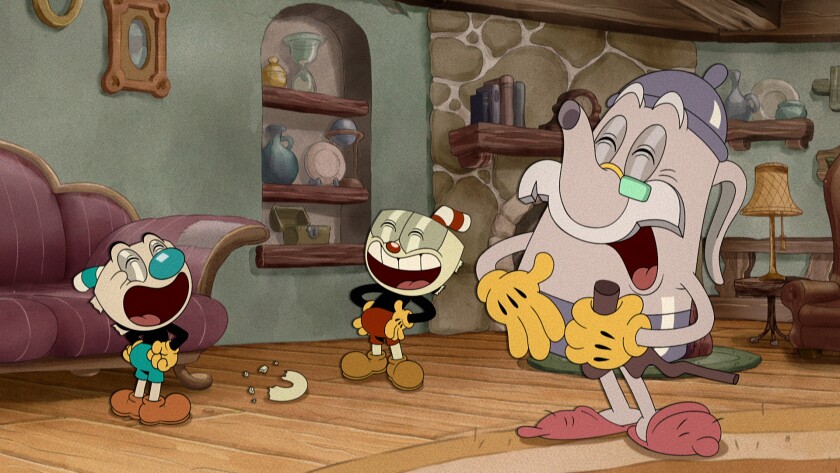

Cuphead (Tru Valentino), left, and Mugman (Frank Todaro) in an episode of “The Cuphead Show!”

(Netflix)

Among the hallmarks of 1930s cartoons that still delight the Moldenhauers are the energy of loose, rubber-hose characters and the disregard for the rules of physics in service of a gag.

“Another part of what I love about the old cartoons is there was always just a hint of nightmare to it,” said Jared Moldenhauer. “It wasn’t a horror show, but they didn’t have the constraints of wondering what kids would think. … It’s just that hint of eerie. It’s like the most joyful nightmare you can have, essentially.”

All these elements are channeled into “The Cuphead Show!”

The brothers recall showing their videos to their friends when they were younger and learning many of them had never seen that style of animation before.

King Features president CJ Kettler, who also serves as an executive producer on the series, sees “The Cuphead Show!” as a progression of the Moldenhauers’ experience sharing vintage animation through these VHS tapes and the “Cuphead” video game.

“We’re going to do the exact same thing with the series because there’s a whole generation of kids who’ve grown up with CGI, and they don’t necessarily have the same level of appreciation for this incredibly beautiful, looks-like-hand-painted animation,” said Kettler. “And now this generation of kids will see it for the first time and go, ‘Oh, my God, I’ve never seen anything like that.’ I think it’s exciting to have the next generation get turned on to it.”

“The Cuphead Show!” character visual development by Dave Wasson.

(Dave Wasson / “The Cuphead Show!”)

Beyond the differences between the 3DCG animation that dominates films and the 2D animation seen more often on TV, modern tools and pipelines mean 2D animation is made differently now than it was in the 1930s.

But the goal on the show, said Wasson, was “to try to make it look as much like a cartoon that could have been produced back at that time.”

For character animation, this involved supplementing hundreds of “special poses” or unique illustrations to the animation software used for the show so the 2D character puppets look as much like traditional animation as possible.

“I think people tend to forget the pipeline to produce that look just doesn’t exist anymore,” said Fernandez. The 1930s was “like the most ambitious time in animation — people were just going at it. You had painters who were coming from these prestigious painting schools and illustration schools now learning how to do animation. To re-create that level of art was actually really daunting and difficult for a modern TV pipeline.”

Figuring out the look of the series involved a long research-and-development process, studying how animation was made during a decade that spanned from black-and-white cartoons to Disney’s “Snow White” (1938). It was a task that involved not only synthesizing a style that felt like it was born of that era but also making it one that could be sustainable for the people working on the show and that would appeal to a modern audience.

Fernandez explained there was a lot of trial and error, and she found that there were no real shortcuts.

Re-creating the lush, vibrant looks of the vintage watercolor backgrounds, for example, involved the same process of painting layer by layer as would traditional painting. The only real difference was that it was done using digital tools rather than paper.

“The creative process is actually almost exactly the same,” said Fernandez. “The artist is the same, it’s coming from the same place. The time, the labor, the love — it’s all the same in that respect. It’s just our tools have been updated.”

Mugman (Frank Todaro), left, Cuphead (Tru Valentino) and Elder Kettle (Joe Hanna) in an episode of “The Cuphead Show!”

(Netflix)

Even the stereoscopic animation involved some adaptation and learning because it’s a technique the team did not have experience with. Working with stop-motion animation specialists from the L.A.-based Screen Novelties, “The Cuphead Show!” creatives had to figure out how to track the 2D animation onto the sculpted 3D background sets.

“The last thing you want is a character to be walking and the background sliding under their feet,” said Wasson. “It breaks the illusion if it doesn’t look like they’re actually planted in the environment. We all learned making this show — even people that were the experts.”

Besides the tools and pipeline, one of the biggest differences between the 1930s and now is the sensibilities of modern audiences. Whereas audiences in the 1930s would be wowed just by seeing a drawn character moving, audiences now require additional storytelling elements, like appealing characters and comedic timing, to fall into the thrall of a show.

“The animation style kind of evolved on us,” said Wasson. “When I started, I [thought] we were going to do rubber-hose animation and really stick to that. But what I quickly came to realize is we’re doing character-driven stories, so we need these characters to be able to act and have expressions and emotions that you can read.”

And though the character and background designs are heavily influenced by vintage cartoons, “you don’t have to know anything about the 1930s” to enjoy the show, he said.

“It’s not like we made this show that’s [just] for animation scholars,” said Wasson. “If you don’t know anything about it and you just like funny pictures, you can still watch [the show]. Hopefully it will introduce a whole new generation of audience to this style.”

Images and Article from www.latimes.com