Shared from www.latimes.com

Something interesting is happening in the “Progressive R&B” category at this year’s Grammy Awards. Four of the six nominated albums contain songs that bear the unmistakable rhythmic signature of a Detroit hip-hop beat-maker named James Dewitt Yancey, known professionally as “Jay Dee” or “J Dilla,” who died 16 years ago, at the age of 32, from a rare blood disease. On the lineup of L.A.’s upcoming Smokin Grooves music festival in March, nearly half of the artists were Yancey’s collaborators or are students of his style.

Both events speak to J Dilla’s enduring influence as a composer and producer, even though he never had a record that made it into the top 20 on the pop charts. At the peak of his career in the 1990s and 2000s, he worked with a legion of famous artists like A Tribe Called Quest, Busta Rhymes, the Roots, Common, D’Angelo and Erykah Badu — often without explicit or full credit. Nor did he attain the success of his more visible contemporaries such as Timbaland and Dr. Dre.

In the years after J Dilla’s death in 2006, his birthday became the occasion for annual celebrations by fans around the world, his music was interpreted for symphonic orchestras, and he got more media attention than he ever did when he was alive. The Guardian has called J Dilla “the Mozart of Hip-Hop.” NPR heralded him as “Jazz’s Latest Great Innovator.” His collaborators Questlove, Common and Madlib have likened him to Duke Ellington and John Coltrane.

Why does Dilla — whose main instrument was a drum machine — deserve to hang in the same league as these musical luminaries? How does a beat producer enter our canon? It has to do with our conception of musical time.

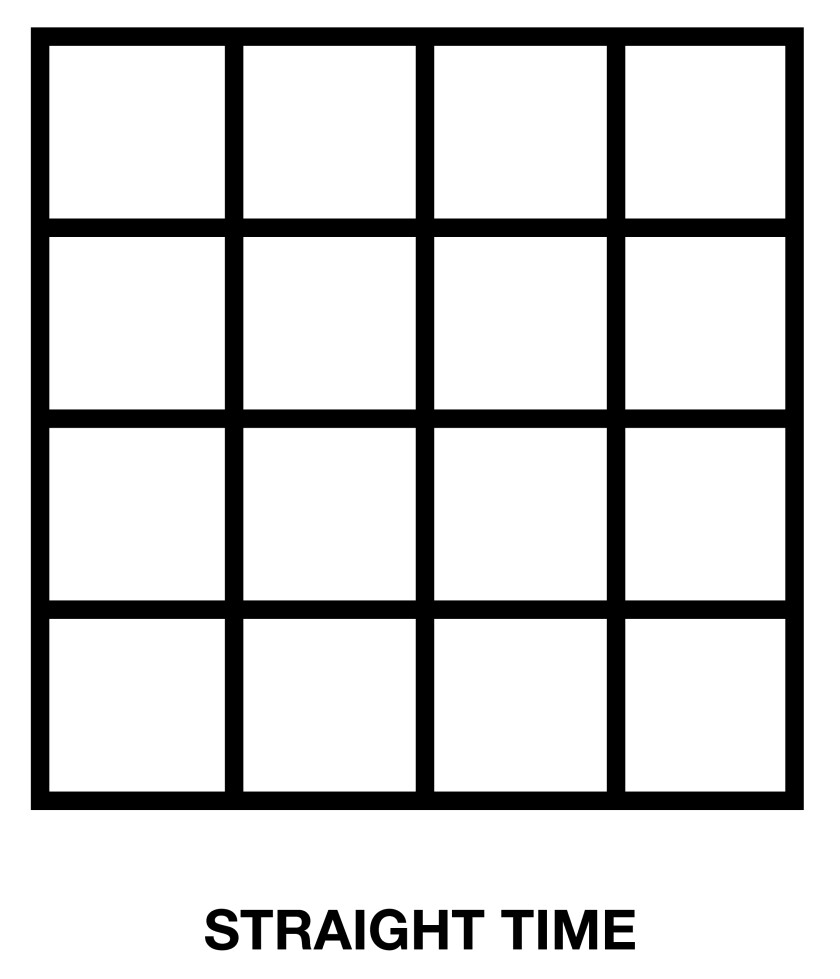

European music, whether high classical or low folk, traditionally counts its rhythms evenly, in what we call “straight time.” Every beat is of equal duration.

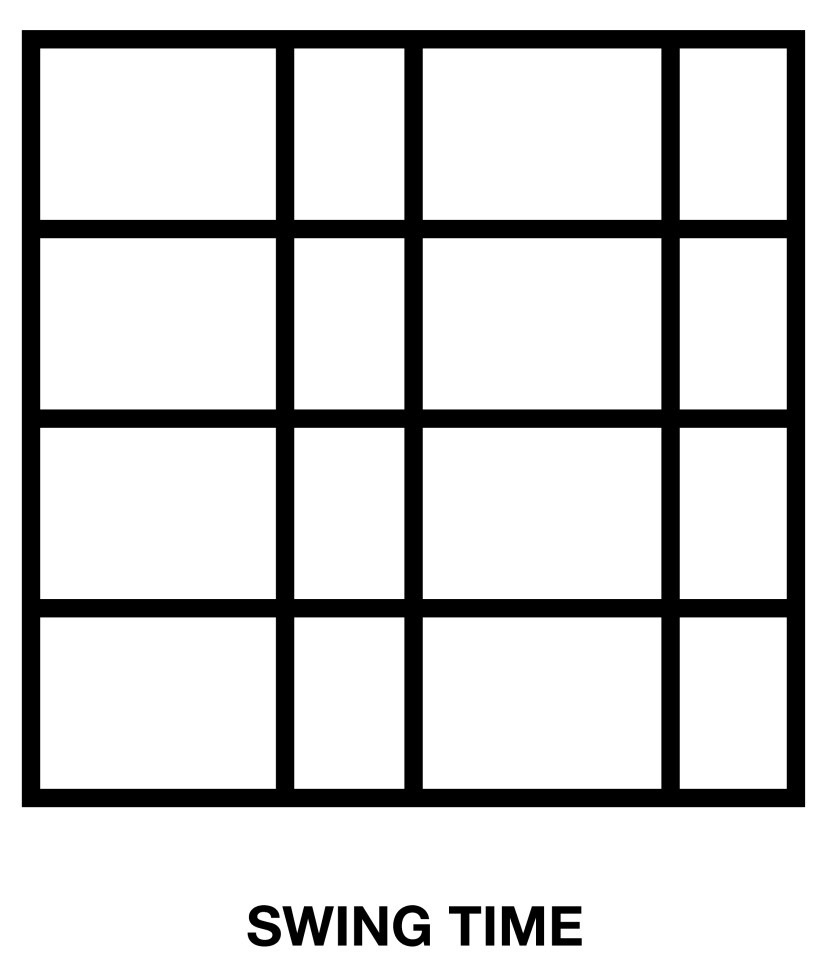

In North America, an uneven time-feel, developed by African Americans and entering our culture through blues and jazz, evolved, wherein beats come in couples of long-short, long-short. It came to be called “swing.” Louis Armstrong, for example, is in our canon partly because he helped to codify swing into our collective playing and singing.

When music is “swung,” the degree of unevenness varies by the performer and the performance, making it difficult to document using traditional European musical notation. But these two time-feels, straight and swing, have dominated our popular music for the past 100 years, sometimes inhabiting the same piece of music. In Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody,” for example, around the four-minute mark, the straight rhythms of European opera give way to the swung rhythms of American rhythm and blues, making a journey of 4,000 miles and 400 years in eight seconds.

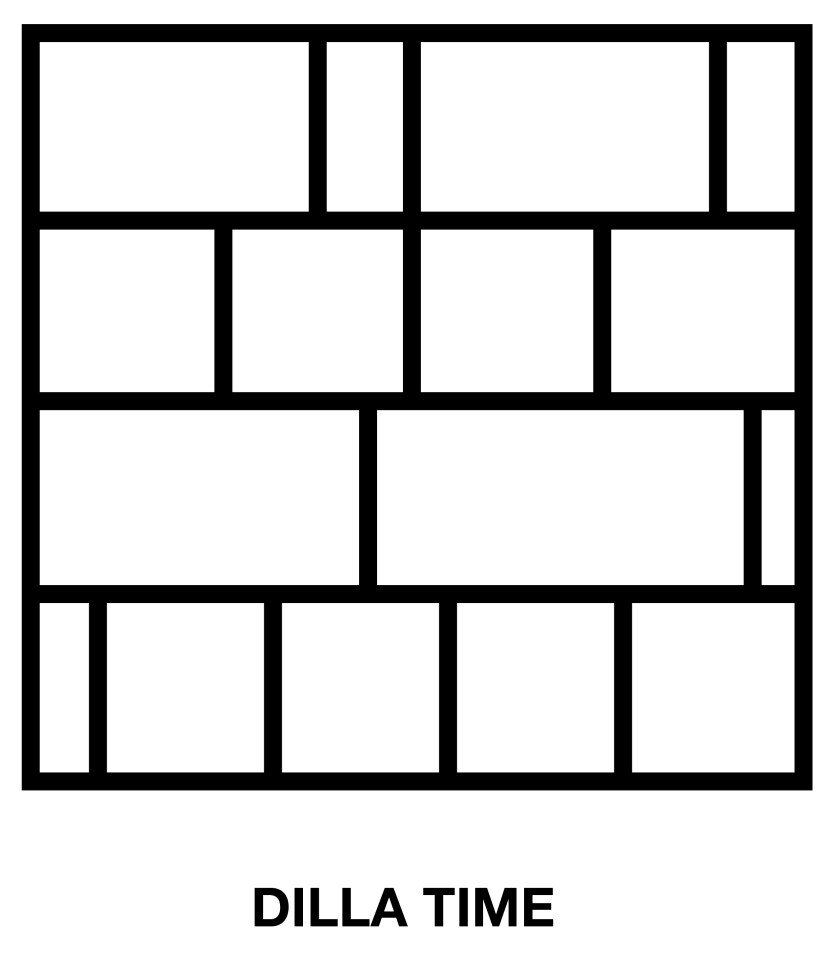

In 1998, a new time-feel began to emerge from a basement in Detroit, where James Dewitt Yancey noticed that his drum machine, the Akai MPC-3000, allowed him the freedom to displace sounds in microscopic ways that created a disorienting rhythmic friction: not straight, not swung, but multiple pulses of straight and swung simultaneously. In the course on popular music that I teach at New York University, we named this conflicted time-feel for its progenitor: Dilla Time.

Jay Dee/J Dilla had been playing with error and “offness” in his rhythms since his professional debut in 1995, but these new Dilla Time tracks — which made their way into the world through his informal “beat tapes” and the yet-unreleased debut album by his group Slum Village — had a bizarre, limping, woozy quality to them.

None of this would have mattered had these subversive rhythms not been so attractive to other beat-makers, and to a core group of hip-hop friendly musicians that included D’Angelo and Questlove, who enacted Dilla’s micro-rhythmic conflict with traditional instruments on the 2000 album “Voodoo.”

Dilla’s rhythms soon permeated R&B and pop — Michael Jackson’s final charted single, “Butterflies,” was programmed in Dilla Time — and by the late 2000s they had begun to convert a new generation of serious jazz players. The “Dilla feel” is now ubiquitous in jazz clubs and conservatories and has transformed the way traditional musicians approach their instruments. Dilla’s musical ideas resonate in the work of Guggenheim fellows such as David Fiuczynski and Pulitzer Prize-winning pop icons such as Kendrick Lamar. That is an innovation and an influence of centenary proportions.

Some point out that straight and swung have collided briefly before J Dilla, in the work of pianists like Errol Garner. And micro-rhythmic conflicts are present in some folk music throughout the world. But there is much more to J Dilla’s genius than just his rhythmic work. He was a master at sampling harmonic and melodic material and recombining it with sophistication. He was a virtuoso who could change the textures, timbres and envelopes of sound in emotionally evocative ways. He was, above all, a deep listener, and his own listeners were the beneficiaries of his bionic ear.

It has been said by some that J Dilla “humanized” his drum machine. It is quite the opposite: He used his drum machine to make a kind of rhythm that no drummer had ever made before. But there is indeed a less conceptual, more human reason that we now count J Dilla among the greats and why his drum machine is now on permanent exhibit at the Smithsonian, near Thomas Dorsey’s piano, Louis Armstrong’s trumpet, Chuck Berry’s Cadillac and George Clinton’s Mothership. His harmonies made people weep, and his rhythms made them feel free.

Dan Charnas is a journalist and a professor at New York University. His latest book is “Dilla Time: The Life and Afterlife of J Dilla, the Hip-Hop Producer Who Reinvented Rhythm.”

Images and Article from www.latimes.com