They were just two friends from Long Island. One was a failed potter, the other a med school reject. But with a $5 correspondence course and a few thousand dollars, Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield went from scooping ice cream in a Vermont gas station to building a brand recognized around the globe—not just for its chunky, funky flavors, but for its unapologetically progressive politics.

Nearly five decades after they launched Ben & Jerry’s, the company is now at the center of one of the strangest corporate dramas in modern business. What began as a homespun experiment in socially conscious capitalism has become a billion-dollar brand locked in a bitter standoff with its parent company. The ice cream is still sweet. But the relationship? Frosty.

From Gym Class to Gas Station

Ben and Jerry’s story began in a seventh-grade gym class in Merrick, New York. Fast friends from their teen years, the two reconnected in their twenties, both a little lost. Cohen was trying to sell pottery. Greenfield was trying—and failing—to get into medical school. In 1977, they decided to go into business together.

They considered bagels, fondue, and other trendy snacks, but ice cream won out—it was cheaper to make. To prepare, they split a $5 Penn State correspondence course on ice cream production, reading mailed textbooks and completing open-book exams. That course, originally developed in 1892, still exists today.

Pooling $12,000—$4,000 each, plus a bank loan and some help from Ben’s father, they opened their first scoop shop in 1978 in a dilapidated gas station in Burlington, Vermont.

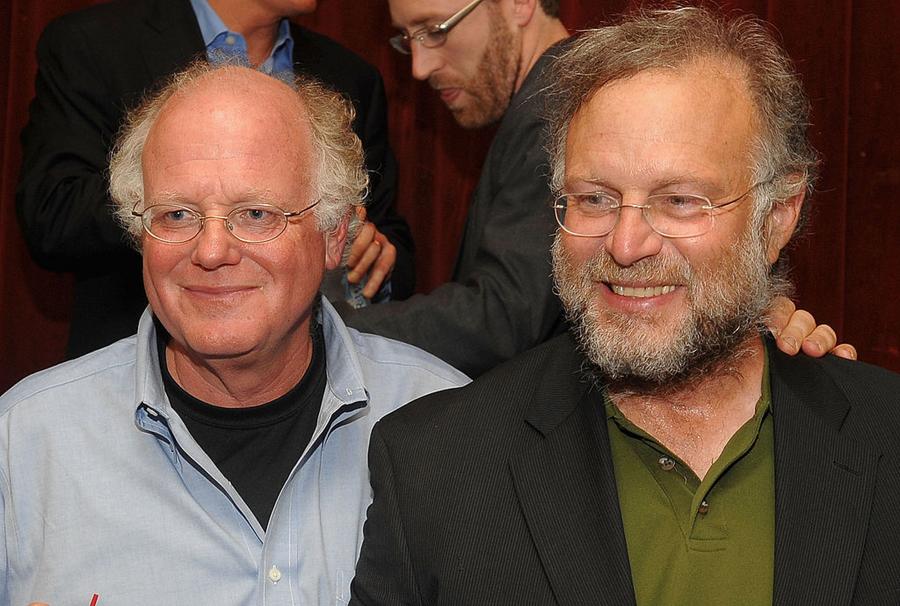

(Photo by Steve Liss/Getty Images)

Why the Chunks?

Ben Cohen has anosmia, a condition that limits his sense of smell and taste. To make the ice cream experience more satisfying for himself, he relied on texture. That’s why Ben & Jerry’s became famous for its over-the-top mix-ins—brownie bits, cookie dough, nuts, and swirls of caramel, fudge, and marshmallow. The texture wasn’t a gimmick. It was personal.

The brand’s early success was meteoric. By the mid-1980s, pints were available in grocery stores across the U.S. In 1984, the company went public. By 1987, Ben & Jerry’s was worth $30 million (roughly $68 million today). They fought off corporate bullies, including a fierce legal battle with Häagen-Dazs’ parent, Pillsbury. The more they punched up, the more customers loved them.

But staying independent didn’t last.

Selling Out Without Giving In

In 2000, Unilever bought Ben & Jerry’s for $326 million. That’s the same as around $600 million in today’s dollars.

It was a bittersweet deal. The founders didn’t want to sell, but as a public company, they had to entertain shareholder offers. To preserve the brand’s mission, the deal included an unusual clause: Ben & Jerry’s would retain an independent board empowered to make decisions about its social activism and values.

That arrangement would become both a safeguard and a source of major conflict.

Unilever helped take Ben & Jerry’s global. The brand now sells in 43 countries and generates an estimated $1 billion in annual sales. But the partnership has been anything but smooth. Over the years, Unilever clashed with the independent board on everything from marketing campaigns to ingredients to political statements. The tension boiled over in 2021 when Ben & Jerry’s announced it would halt sales in Israeli-occupied territories, citing human rights concerns. The move sparked backlash, boycotts, and lawsuits. Unilever, in turn, sold the Israeli business without board approval. Ben & Jerry’s sued its own parent company.

Then came more rifts: the ousting of CEO David Stever, pressure from investors over the brand’s politics, and even internal fights about whether the company could issue a statement calling for a Gaza ceasefire. On Wednesday, co-founder Ben Cohen was arrested during a Senate protest over U.S. aid to Israel. He was filmed being led out of the Capitol in handcuffs.

The Breakup and the Buyback Attempt

In March 2024, Unilever announced it would spin off its entire ice cream division—including Magnum, Breyers, Klondike, and Ben & Jerry’s—into a standalone business. Analysts estimate the group brings in about $9 billion annually, but growth has been sluggish. Sales rose just 2.3% in 2023, the slowest among Unilever’s divisions, with high prices prompting lower consumer demand.

For Unilever, the cold supply chain, seasonal sales patterns, and ongoing political headaches made the ice cream business more trouble than it was worth.

Ben Cohen saw an opportunity.

In 2025, he launched a long-shot effort to buy back Ben & Jerry’s from Unilever. He’s actively seeking like-minded investors, hoping to return the brand to independent ownership while preserving its activist mission. “If you love us, let us go,” he said, calling on Unilever to let the brand operate free from corporate constraints. So far, Unilever has said Ben & Jerry’s is not for sale as a standalone entity.

Still, the brand’s independent board remains legally protected, even under a spinoff. That firewall—built into the 2000 acquisition—continues to shape one of the most complex, emotionally charged deals in corporate history.

Jamie McCarthy/Getty Images

A Company With a Soul

Ben & Jerry’s isn’t just about ice cream. It’s about values—however messy, inconvenient, or controversial they may be. That ethos has earned the company millions of loyal fans, even as it alienates others.

Cohen and Greenfield, now in their 70s, still live near headquarters in Vermont and remain involved. They show up at franchisee events, speak at employee gatherings, and lend their voices to causes like climate action and criminal justice reform. They even protest together.

The company they founded in a gas station with a $5 class now generates nearly $1 billion a year and employs thousands. But its future—corporate or independent—remains uncertain.

Content shared from www.celebritynetworth.com.