Nearly half of women over age 40 have dense breast tissue, a factor that increases breast cancer risk, according to the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (BCRF). To bring awareness to this fact, the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) made it mandatory as of Sept. 2024 that all mammography reports tell a patient whether or not she has dense breasts. And while this most definitely has helped women better understand their risk factors and seek additional screening, it hasn’t changed how radiologists read mammograms—which is why it’s so groundbreaking that a new study identified breast texture patterns in dense tissue that may be associated with an increased cancer risk.

RELATED: 85% of Unvaccinated Women Will Likely Get This Virus—And New Research Links It to Heart Disease.

What do I need to know about dense breast tissue?

Dense breast tissue refers to breasts made up of less fatty tissue and more fibrous and glandular tissue—in other words, it’s how your breasts appear on a mammogram. You can not feel dense breast tissue, and it doesn’t cause any pain or changes to the breast.

As Cleveland Clinic explains, because both dense breast tissue and tumors appear white on a mammogram, it can make it harder for a radiologist to detect breast cancer. Dense tissue is also harder for a radiologist to see through.

Moreover, having extremely dense breast tissue in and of itself increases breast cancer risk. “That’s because breast cancer often starts in your fibroglandular tissue, a type of dense breast tissue,” Cleveland Clinic states. “The more fibroglandular tissue that you have in your breast, the greater the chance you’ll develop breast cancer.”

As part of the FDA’s 2024 mandate, mammogram reports sent to your healthcare provider must assign breast tissue into one of four categories:

- Mostly fatty tissue (10 percent of women)

- Scattered fibroglandular breast tissue: There are some areas of dense tissue, but they’re mostly fatty (40 percent of women)

- Heterogeneously dense breast tissue: There is slightly more dense tissue than fatty tissue, which could obscure small masses (40 percent of women)

- Extremely dense breast tissue (10 percent of women)

If you fall into one of the latter two categories, your provider may request a 3D mammogram (in addition to a regular 2D mammogram), a breast ultrasound, or potentially a breast MRI, according to the American Cancer Society.

Dense breast tissue is more common in women under 40, those with a low body mass index (BMI), those with a family history of dense tissue, women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, and those taking hormone replacement therapy (HRT).

RELATED: 50% of Colon Cancer Cases in Young People Tied to 1 Common Factor, Researchers Discover.

New research identified texture patterns in dense tissue associated with breast cancer risk.

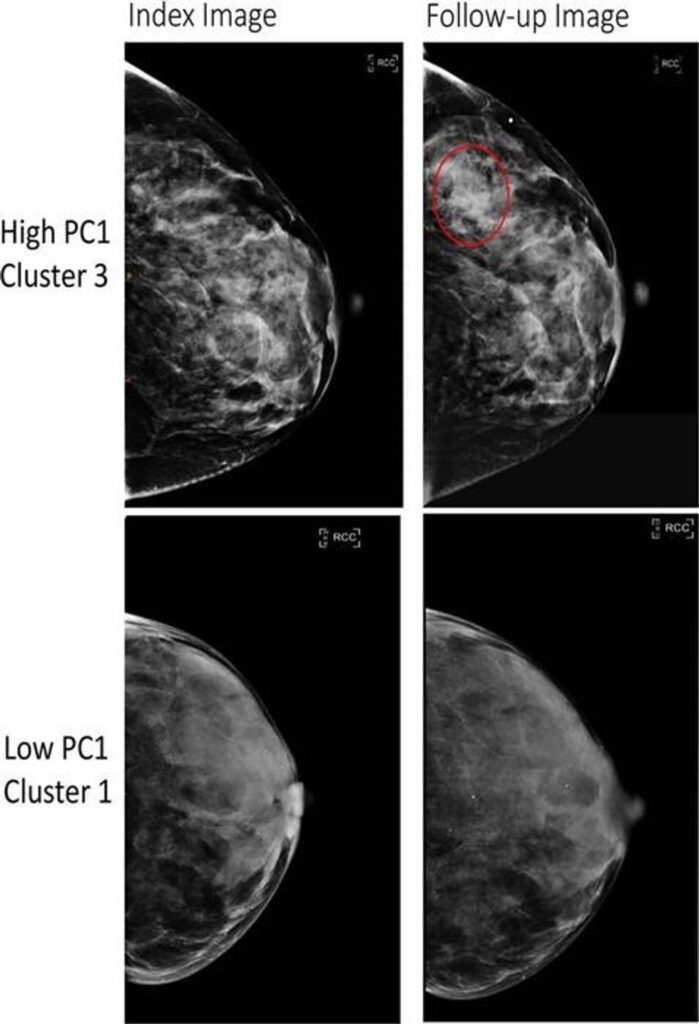

A high-risk phenotype (top) and a low-risk phenotype (bottom). Credit: Radiological Society of North America (RSNA)

The new study, published in the journal Radiology, sought “a greater understanding of the distinct patterns and characteristics of breast tissue, beyond the measurement of breast density” and how that relates to breast cancer risk, states a press release.

To arrive at their findings, the researchers analyzed the mammograms of over 30,000 women without a prior history of breast cancer. From these images, they extracted 390 radiomic features (“patterns and characteristics that might not be visible to the human eye”), which they then grouped into six breast tissue patterns, scientifically known as phenotypes (“quantifiable characteristics or traits”).

These six patterns were associated with an increased risk of breast cancer generally, but they also pointed to two main takeaways:

- The patterns increased breast cancer risk in both Black women and white women

- The patterns were associated with false-negative mammograms (“when cancer is missed on a mammogram”) and interval cancer diagnoses (“cancer diagnosed in between scheduled screenings”)

“We were surprised to find that these radiomic phenotypes showed suggestion of a stronger risk among Black vs. white women,” said co-senior author Despina Kontos, PhD, Herbert and Florence Irving Professor of Radiological Sciences and chief research information officer at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. “This is particularly important as breast cancer tends to be more aggressive in Black women, highlighting the need for novel risk factors in this population.”

“Understanding who is at greatest risk of invasive breast cancer, especially the most aggressive types, is crucial for preventing cancer and diagnosing it early for potentially the choice of less intensive treatments,” added co-senior author Karla M. Kerlikowske, MD, professor of medicine and epidemiology and biostatistics at University of California San Francisco.

Next, the researchers plan to expand their study to a larger group of women in the U.S., “especially examining 3D mammograms, and combining these radiomic risk factors with genetic and other lifestyle factors to improve our ability to define who is (and who is not) at increased risk of invasive breast cancer,” shared senior author Celine M. Vachon, PhD, a professor of epidemiology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

Content shared from bestlifeonline.com.