Benjamin Franklin is easily one of the five greatest United States Presidents of all time. Fittingly, that is why today his face graces our most common paper note, the twenty-dollar bill. You probably have some in your wallet right now.

Ok, before we go any further… did anything I just said seem off to you?

Think about it….

.

.

.

.

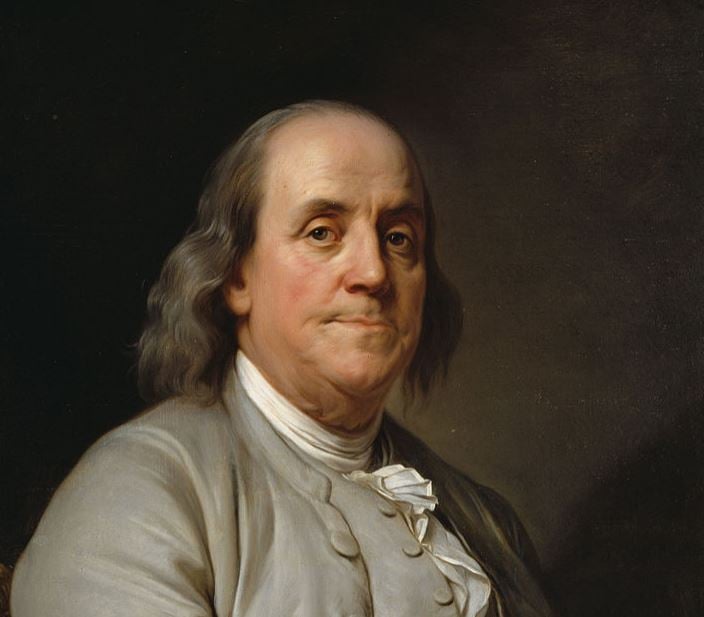

Eagle-eyed readers may have noticed that Ben Franklin does NOT appear on the twenty-dollar bill (that’s Andrew Jackson). He appears on the hundred-dollar bill. AKA the Benjamin. The Benji. The Franklin. The hundy. The hundo. The C-note.

Oh, and I’m also sorry to report that Benjamin Franklin was never President 🙂 Did I trick you? Be honest… is your fifth-grade teacher punching a wall right now?? 🙂

Anyway. Despite never holding the presidency, Franklin’s face graces the highest-denomination bill in circulation—a nod to just how profoundly he shaped America. Inventor, diplomat, writer, philosopher, Founding Father… and, as you’re about to see, financial mastermind.

When Benjamin Franklin died in 1790, Franklin left behind two trust funds—each worth £1,000 for his beloved cities of Boston and Philadelphia. But he didn’t want the money spent right away. He wanted to give compound interest a couple centuries to work its magic.

(Public Domain)

From Apprentice to Icon

Born in Boston in 1706, Benjamin Franklin was the 15th of 17 children in a working-class family. He left school at age 10 and became an apprentice printer to his older brother. By 17, he had moved to Philadelphia with little more than ambition and a knack for self-education. Over the next several decades, Franklin built a printing empire, publishing newspapers, books, and the wildly popular Poor Richard’s Almanack. His business success—and later government positions—made him one of the wealthiest and most respected men in the colonies.

But Franklin didn’t hoard his wealth. He retired from business in his early 40s and devoted the second half of his life to public service, science, and diplomacy. He helped found the first public library in America, the University of Pennsylvania, and what would become the U.S. Postal Service. He also served as ambassador to France, helped draft the Declaration of Independence, and negotiated the peace treaty that ended the Revolutionary War.

When Franklin died at age 84, he was comfortably wealthy. As we mentioned, he was comfortable enough to leave £1,000 to his two beloved cities, Boston and Philadelphia. The money came specifically from his salary as Governor of Pennsylvania from 1785 to 1788—a sum he reportedly believed he shouldn’t have been paid in the first place. Franklin famously argued that public servants in a democracy should not earn salaries, and even tried (unsuccessfully) to get that idea written into the Constitution.

Btw, why did he use pounds sterling instead of US dollars? At the time, the American financial system was still in its infancy. The U.S. dollar wouldn’t be formally established until the Coinage Act of 1792, two years after Franklin’s death. So he chose the most stable of the many currencies that were in circulation.

The Long Game

Franklin’s idea for the trusts wasn’t random. It was sparked by a satirical essay from French mathematician Charles-Joseph Mathon de la Cour, who wrote about the idea of leaving money to grow over centuries through compound interest. Franklin saw potential in turning the theory into real-world philanthropy.

He instructed that the money be loaned to young tradesmen—”young married artificers,” as he called them—who could repay the loans over ten years with 5% interest. After 100 years, a portion of the funds could be used for public works. The rest would continue compounding for another 100 years, at which point it could all be distributed.

Boston’s Big Bet

Boston took a bolder approach to managing its trust, allowing investments in the stock market. After 100 years, the fund had grown to $391,000, some of which helped establish the Franklin Union, a trade school partially funded by Andrew Carnegie that still operates today as the Benjamin Franklin Cummings Institute of Technology.

By 1990, Boston’s trust was worth nearly $4.5 million. But when it came time to distribute the funds, things got messy. A 1958 Massachusetts law had tried to earmark the money for the Franklin Institute technical school, but the state’s Supreme Judicial Court later ruled that the trust could not be prematurely terminated. Legal battles erupted over who had the rightful claim to the millions—city officials, the state, or the school itself. Eventually, the Massachusetts Attorney General ruled that 26% should go to the City of Boston and 74% to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as Franklin had originally outlined.

Ultimately, both the city and the state used their shares to continue funding technical education and training programs, honoring Franklin’s vision of supporting trades and applied sciences.

Philadelphia’s Slower Growth

Philadelphia’s fund grew more slowly—by 1907, it had reached $172,000, and much of it was used to help build the Franklin Institute, the city’s iconic science museum. By 1990, the fund had reached $2 million.

As in Boston, arguments erupted over what to do with the money. The city’s share—about $520,000—was eventually designated for grants to high school graduates pursuing trade careers, which honored Franklin’s original wishes. The remaining $1.5 million was allocated by the state legislature to various community foundations across Pennsylvania, forming Ben Franklin Funds that supported educational and community initiatives like early childhood literacy and vocational training.

Legacy of a Financial Visionary

Next time you spot Ben Franklin’s face on a $100 bill, remember—that’s no fluke. Franklin wasn’t just a founding father; he was arguably the first American to truly grasp the power of long-term investing. He understood the value of money, the value of time, and most importantly, the extraordinary things that can happen when the two are combined.

His £2,000 bequest grew to more than $6.5 million over two centuries. And it didn’t just sit in a vault. It funded schools, scholarships, scientific institutions, and job training programs. It helped real people, just as Franklin intended.

He didn’t just shape a nation. He engineered a financial legacy that still pays off, 200 years later.. He timed a legacy. And more than 200 years later, that legacy is still paying dividends.

Want a modern example of how powerful compounding can be? Here’s what $100 invested in various ways would be worth today:

- S&P 500 (since 1957): $70,000, assuming reinvested dividends

- Google at IPO in 2004: Roughly $4,000

- Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway in 1965: Roughly $2.6 million

- Bitcoin in 2010: A staggering $81 million

Content shared from www.celebritynetworth.com.