Star Wars: Episode III — Revenge of the Sith had one of the all-time biggest rereleases in history in 2025, as it returned to theaters for its 20th anniversary. At the same time, Lucasfilm celebrated Matthew Stover’s novelization of the film by announcing a deluxe edition reissue coming in October. While each of the prequel films has its own book adaptation, Revenge of the Sith’s is the first to get a significant rerelease, and it’s one of the few pre-Disney Star Wars novels that Lucasfilm has reissued. And that might be because Stover’s take on Revenge of the Sith is the best novelization Star Wars has fielded so far.

A core issue with the Star Wars prequel trilogy is that the characters’ motivations are often obscured by unexplained world-building or erratic choices. But Stover’s adaptation offers deeper insights on Anakin Skywalker’s transition to the dark side, addressing the ambiguities of George Lucas’ script. Unlike most novelizations, Stover’s Revenge of the Sith enriches and enhances the original material with thoughtful characterization, interesting perspectives, and astute descriptions of Lucas’ galaxy far, far away.

Anakin’s abrupt turn to the dark side in Revenge of the Sith is still jarring today. While Hayden Christensen’s performance drew criticism, his acting cannot be blamed for the speediness of Anakin’s fall from grace. It requires depths of emotion that are hard to discern in the movie due to its storytelling hiccups. But the novelization offers more insight into the Force, its users, and the political makeup of the galaxy. And Stover’s interior monologues for Anakin fill in some gaps as well, making his willingness to embrace the dark side far more plausible.

Stover describes the fear within Anakin as “a dragon,” which the character feels could be contained if he becomes powerful enough to defeat his enemies. It’s easier to sympathize with him within this context: After being raised as a slave on Tatooine, Anakin has hesitations about blindly accepting the orders of the Jedi Council, the members of which he must refer to as his “masters.”

Guilt over his inability to save his mother, Shmi Skywalker, drives Anakin to search for solutions that the Jedi Council isn’t willing to provide. His Jedi master, Obi-Wan Kenobi, feels the weight of that same burden. While Qui-Gon Jinn is only briefly mentioned in the theatrical cut of Revenge of the Sith, Stover’s novelization shows that Obi-Wan has been haunted by the death of his former master, who he felt would have been a better instructor for Anakin. Obi-Wan believes he could have helped Qui-Gon defeat Darth Maul in their first encounter on Tatooine during the events of The Phantom Menace. If Darth Maul hadn’t subsequently killed Qui-Gon on Naboo, Obi-Wan feels, Anakin might not have felt such a need for a new mentor, and might not have been open to Chancellor Palpatine’s offers.

Obi-Wan’s compassion for Anakin is exemplified by his insistence that they are “brothers” as of Revenge of the Sith, since he no longer feels that he has anything to teach his apprentice. While the film depicts Obi-Wan as a dutiful follower of the Jedi Council’s orders, Stover suggests that he privately disagrees with its treatment of his apprentice. In addition, Obi-Wan openly objects to having Anakin spy on Palpatine, feeling that it will only breed more distrust. This explains why Obi-Wan is selected to hunt down General Grievous on Utapau; Palpatine removes Obi-Wan from Coruscant to create the perfect opportunity to spring his trap.

In the film, Grievous is introduced abruptly, but Stover digs into why Palpatine is so keen to have a cybernetic warlord as the commander of the Separatists’ droid army. Count Dooku, he feels, is too clever to be left alive — Dooku had assumed he would be part of the scheme to take over the Republic. Stover notes the privileges Dooku has earned from his wealth, and how he views people as “things,” not individuals. While Grievous and Dooku don’t interact in the film, Dooku’s assessment is that the droid general is a “revolting creature” that could never possess the true power of the dark arts.

Stover even gives more context for Dooku’s look of surprise when Palpatine orders Anakin to execute him. The book describes how he was under the impression that the plan was to kill Obi-Wan, then reveal the truth about Palpatine’s plans to Anakin. Dooku, Palpatine, and Anakin would then conclude the war, and serve as the ringleaders of a new galactic order. Dooku’s last moments are more graphic in the book: After Anakin slices off his hands one at a time, Dooku begs for his life before being decapitated.

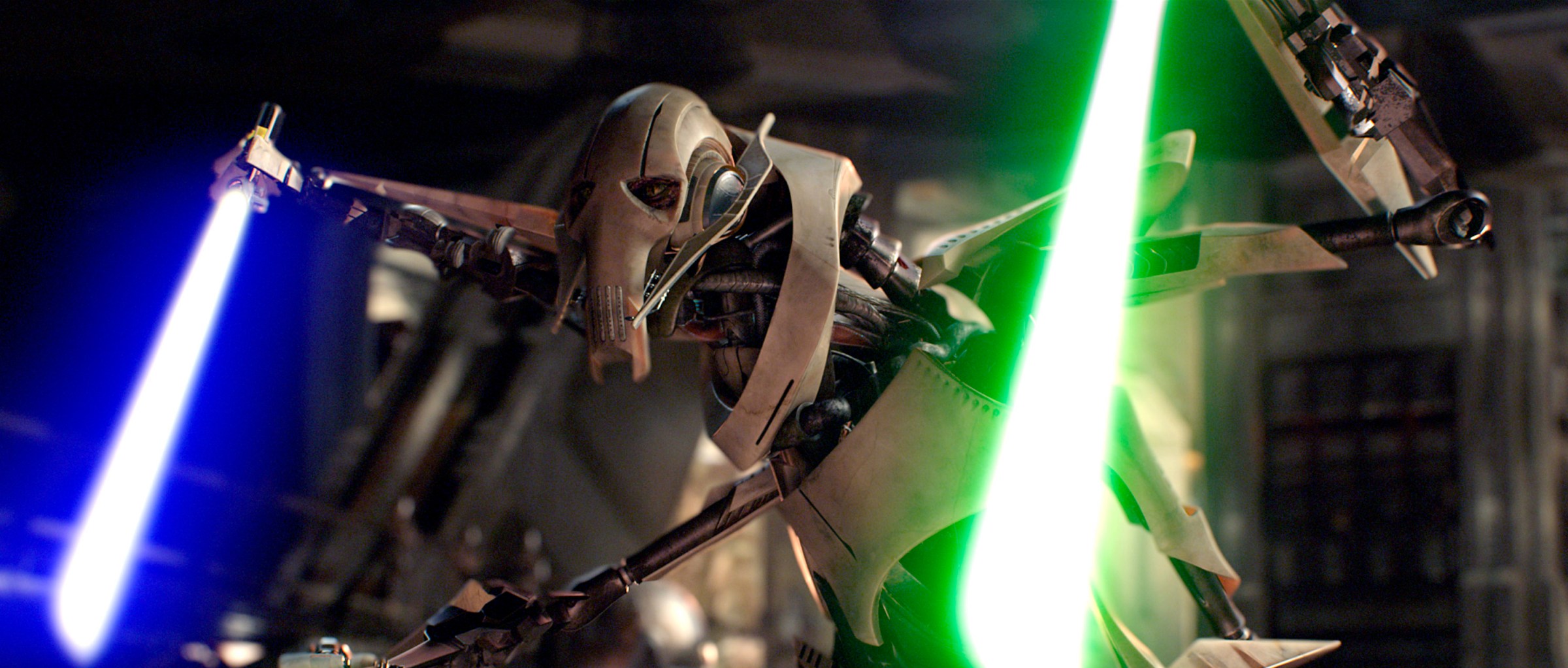

While Grievous is a pawn who serves as an excuse for Palpatine to continue the war after Dooku’s death, Stover gives the droid more personality than the movie does. In addition to killing several Neimoidians who were present above Grevious’ ship Invisible Hand, Grievous shows trepidation upon encountering Obi-Wan and Anakin, as he recognizes that they are more accomplished than the other Jedi he’s faced. The book also expands on Grievous’ training under Dooku. While his lack of Force sensitivity makes it impossible for him to ever be considered a true apprentice, Grievous relishes any opportunity to kill Jedi, believing that his cybernetic enhancements and lack of Jedi compassion make him superior to them.

Grievous, like the entire Clone War, is a diversion that Palpatine uses to distract the Jedi. While the tactical advantage of the Wookiee homeworld of Kashyyyk is not explicitly stated in the novel, Stover indicates that Kashyyyk was invaded to draw Yoda away from Coruscant, depriving Anakin of another mentor. Mace Windu, despite his long tenure as Yoda’s second-in-command, does not truly understand how the dark side tempts Anakin or the fact that Anakin needs protection and counsel. Mace still believes in the prophecy of the “Chosen One,” and thinks Anakin is incorruptible. And he feels that assigning Anakin to spy on Palpatine would sabotage the positive bond they’ve formed.

The story Palpatine tells Anakin about the “tragedy of Darth Plagueis the Wise” — which has become an internet meme in recent years — is far less ambiguous in Stover’s depiction. Palpatine reveals that Plagueis was his master who he killed in his sleep. His ruthlessness is of little concern to Anakin, as the Chancellor tempts him with the possibility of owning everything from a new speeder to the entire star system of Corellia. Palpatine may see this as an opportunity to test Anakin’s greed, but Anakin’s thoughts are actually centered on providing a safe haven for Padme, who Anakin knows is pregnant.

Stover’s description of lightsaber combat removes much of the silliness that shows up in the theatrical version of the story. He adds insight on the seven forms of combat taught within the Jedi Order, including Vaapad, the style Mace Windu has perfected. Mace’s attempt to arrest Palpatine is less abrupt in the book: It takes Palpatine more than a few seconds to dismantle and dismember the other Jedi Masters who accost him. Although he decapitates Saesee Tiin and catches Agen Kolar off guard, Palpatine does not execute Kit Fisto until moments before Anakin arrives.

Mace’s downfall is a strategic failure, as Stover suggests that Palpatine feigns weakness to frame himself as the victim; it’s only in Mace’s last moments that he recognizes that Anakin’s desire to protect Padme will supersede everything else. And while Palpatine is blasted with Force lightning, his ghastly appearance is intended not as the outcome of that fight, but as a reveal of his true form. He remarks to Anakin that he will “miss the face of Palpatine, but the face of Sidious will serve.”

There’s little dramatic tension within either of the lightsaber duels at the end of Revenge of the Sith, as viewers who have seen the original trilogy know that all four combatants will survive. Nonetheless, Stover shows that Obi-Wan and Yoda are both faced with ultimatums. Yoda realizes he must go into hiding, as he no longer has the insight to lead the Jedi Order because he failed to prevent the collapse of the Republic. At the same time, Obi-Wan wrestles with the responsibility of having to kill Anakin.

Prior to the duel, Yoda rejects Obi-Wan’s speculation about why Anakin joined the dark side with the remark “why matters not; there is no why,” an homage to his famous “do or do not” line from The Empire Strikes Back. Nonetheless, Obi-Wan prolongs the duel with Anakin by consistently attempting to disarm him; the drawn-out battle ensues because he is not willing to kill his “brother.”

One of Revenge of the Sith’s biggest question marks is Obi-Wan’s willingness to let Anakin burn alive in molten lava, an unusually cruel fate for someone he claimed to love. Although Stover mentions that Obi-Wan feels that killing Anakin will “burn his heart to ash,” he also admits that it “would be a mercy to kill him,” but that “he was not feeling merciful.” Nonetheless, Obi-Wan’s reasons for departing Mustafar so quickly are ultimately practical, not philosophical. Making the extra effort to kill Anakin would cost Obi-Wan time, and he intends to flee the planet before Palpatine arrives. While his departure from the duel may still feel abrupt, Obi-Wan is under the impression that Padme can still be saved.

Stover shows that Anakin’s transition into Darth Vader is less seamless than the film implies. While on the operating table being fitted with artificial limbs, Vader is tormented by the knowledge that he killed Padme. Instead of the cringe-inducing cry of “no!” that appears in the movie, Vader spends time adjusting to his lack of autonomy, with Stover likening him to “a painter gone blind.”

The freedom of an extended novel meant Stover could include moments in this book that were cut from the film for time. Qui-Gon’s ghostly interactions with Yoda and the establishment of Mon Mothma’s Rebel Alliance are included in full. But the brilliance of Stover’s novel isn’t in his additions; it’s in his contextualization. Lucas put many of the right pieces in place, but Stover presents them in a more forceful way — pun intended.

Content shared from www.polygon.com.