In her recent exhibition at Magenta Plains, Ebecho Muslimova stretches the world around her recurring protagonist “Fatebe,” granting her new kinds of architecture and absurdities to explore. Homing in on themes that are more grotesque and sci-fi like, Fatebe starts colliding with objects that defy her cartoonish two-dimensional reality, which Muslimova, while on a call with fellow artist Carroll Dunham last week, dubbed the “Roger Rabbit Effect.” Phoning in from his Connecticut studio, the 75-year-old Dunham has also spent his career with humanoid, “Disney-line” formed characters that open up new vessels for storytelling, demonstrated most recently at his solo show at Max Hetzler in London, where bodily exploration and a cartoon dog take center stage. Whilst the two artists had only met once before, their shared interests and influences meant that they had a lot of ground to cover, from consciousness and comic books to the eternal question of when, and how, to kill off your avatar. “It’s fun for us to talk,” Dunham said. “I feel like there are quite a few overlaps in our attitude.”

———

CARROLL DUNHAM: I’m sorry we’ve never met in person.

EBECHO MUSLIMOVA: We have actually, and I wanted to remind you.

DUNHAM: When did we meet? I’m sorry, I don’t remember.

MUSLIMOVA: It’s okay, I barely remember. I think it was 2015. It was my second group show ever in Zurich. There was no reason why I should have been there because I had no career. But that night spiraled out into some sort of drunken debauchery, and I remember the next day you approached me and I was non-verbal, hungover, and you said something like, “We’ll talk another time.”

DUNHAM: [Laughs] Well, I guess here we are talking another time. I know that it’s probably the first time I saw your work, but I’ve been aware of it for a while.

MUSLIMOVA: Well, I’ve always been aware of your work.

DUNHAM: Where do you live?

MUSLIMOVA: I’m back and forth from New York to Mexico City.

DUNHAM: So is your studio in Mexico City?

MUSLIMOVA: My studio officially is in both places, but I’m working right now in Mexico City. I’m a true die-hard New Yorker, and I never thought I would leave, but here I am.

DUNHAM: It’s good to do that. Well, I just recently saw the paintings of yours that are up in New York.

MUSLIMOVA: I’m so glad you saw.

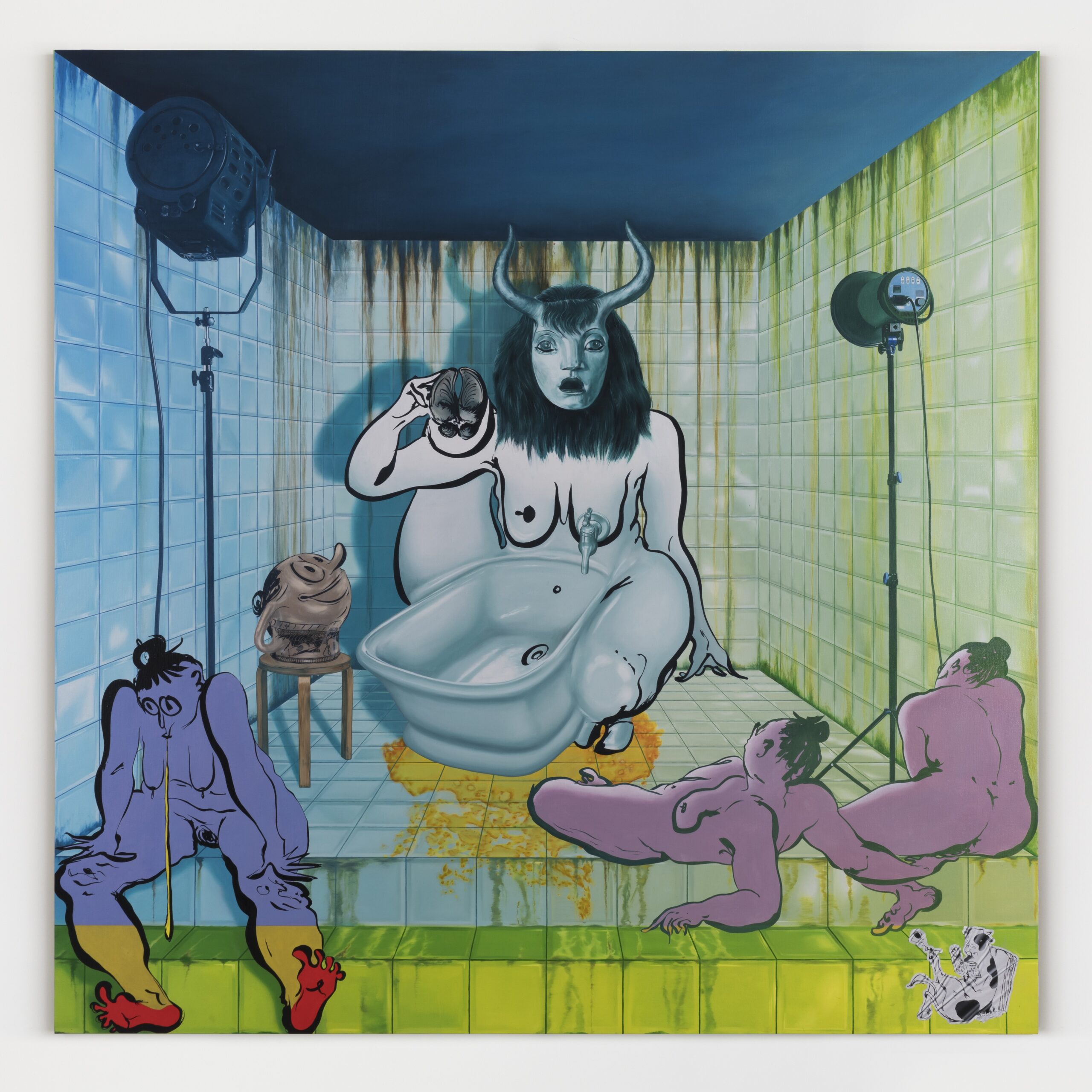

Ebecho Muslimova. Fatebe Io Stalled, 2024. Oil on canvas. 72 x 72 in.

DUNHAM: I really find them interesting. There are a few things I feel close to in a way. First is this idea of making painting that’s driven by a character. The way you’re involved with that is probably different from the way I’m thinking about, but just as a way to structure your activity, I relate to it a lot. And also the fact that drawing seems to be the foundation of everything you’re doing.

MUSLIMOVA: I was going to say the same about our work. I mean, my character is an entity. She has a personality that’s distinct, but the character’s psyche is a vehicle to figure out things.

DUNHAM: Right, and it’s clearly not just storytelling. It’s about making painting situations, different spaces, different constructions.

MUSLIMOVA: Well, the character both as a narrative and as a formal tool to self-organize almost gives permission or justification to then expand into architecture.

DUNHAM: To make places for the character and situations that the character can inhabit.

MUSLIMOVA: Yeah, in a really dumb, elemental way. The body has to be somewhere.

DUNHAM: Yeah. It’s the whole way of thinking about stuff. I read part of an interview that you gave where you spoke about this, but the fact that the character is so flat, it could almost look screen printed.

MUSLIMOVA: I like to call it the “Roger Rabbit Effect.”

DUNHAM: Yeah, that was good. I remember that movie very vividly, that whole thing they were trying to do to put an animated character into a so-called real place.

MUSLIMOVA: I was looking at pictures of your show in London. I wish I could have seen it in person, but I’m thinking about the space within the space, the architecture within the architecture. Is that new?

DUNHAM: Yeah. This story has evolved out of things I was drawing and thinking about. What I’ve been doing is just not illustrating in the sense that there’s a plot–there’s no story. It’s just that situation that’s depicted, and I seem to keep making it over and over and over. It has to do with an image of a studio and a person working in a studio, and then the studio is in another place, and then all of that is in the painting. So it’s these different spaces that hold other spaces. I’ve never really worked so consciously on that sort of construction before.

MUSLIMOVA: Well speaking of character, there’s the body that keeps repeating that is flat. But all of the paintings I’m doing right now are also situated in a specific room. Not the studio, but a gallery in which they will be shown. So more and more architecture has been reappearing in my paintings. I used to think that it was putting the thing in the room, but now I realize that the architecture is the other character that somehow has its own thing.

DUNHAM: I’ve never put it to myself that way, but I completely get how you’re representing it, that the spaces are like characters. It really weirded me out a lot when I realized I was kind of drawing my own studio. Well, you tell yourself all kinds of stuff. I’ve told myself and other people a lot of bullshit about my own work, that I need that in order to even make them. You set up this whole thing and this way of talking about it that gives you some distance from it.

MUSLIMOVA: But do you know that you’re lying? Not lying, but do you know yourself that this will change and is a falsehood, that it’s just a permission?

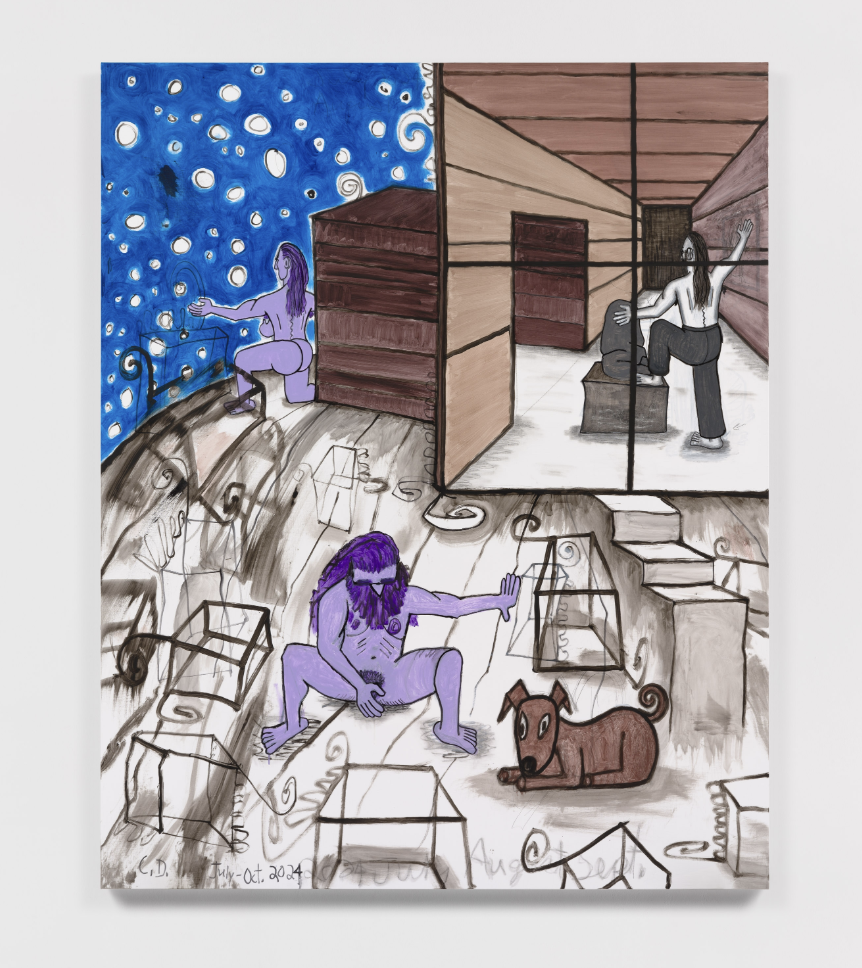

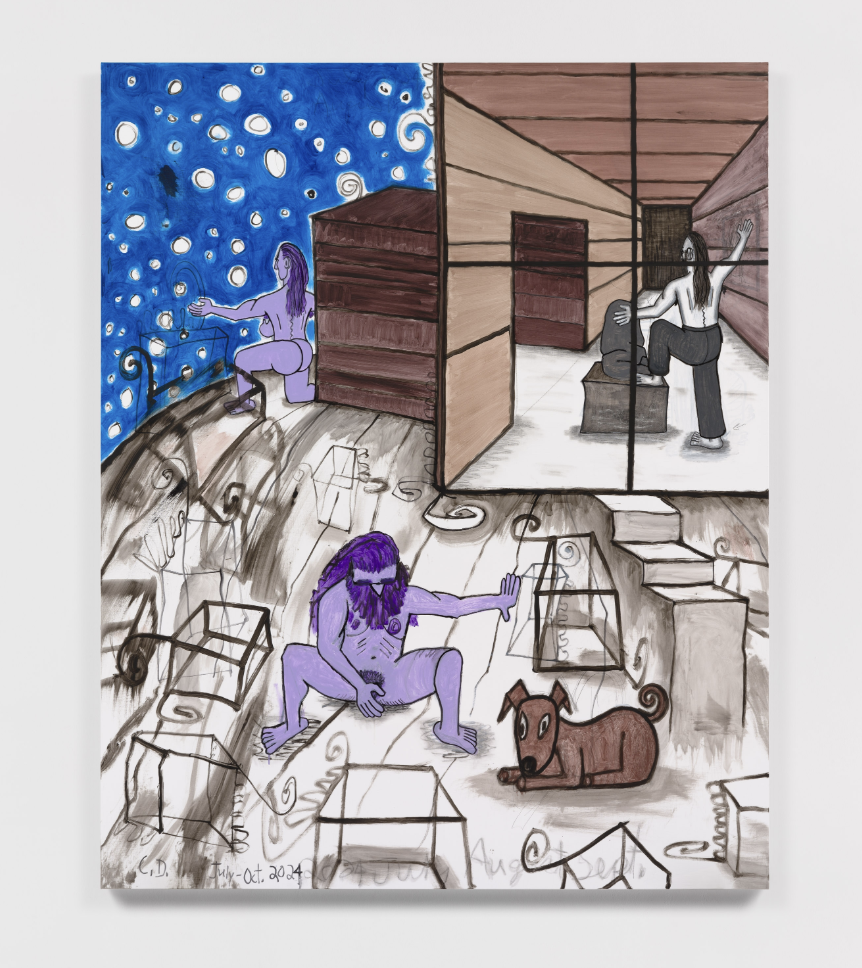

Carroll Dunham. Open Studio (4), 2024. Urethane, acrylic and graphite on linen. 74 x 60 in.

DUNHAM: I would say I’ve begun to suspect. For years, I didn’t. I started out absolutely, almost ideologically committed to the idea that I was going to make abstract painting. And very quickly, all these things started to come into the paintings that were representations of things that I was not really owning. People would tell me, “Oh, it’s this, it’s that.” And I would say, “Now you’re projecting. It’s not.”

MUSLIMOVA: Projecting is a big part of it. We make the paintings and then the projections finish off the work.

DUNHAM: I mean, we have our own projections about what we’re doing, and you start to learn that when your work is seen by more people. Then you have to process what they see. Then that comes back in as information that probably affects how you think about what you’re doing.

MUSLIMOVA: I also tell myself a script to start working, but I have by now understood that that has nothing to do with what the painting means to me later. I really try to not hold on to any sort of promise because it’s a front. It used to panic me that I only understood what the painting was way after it’s done, and only what I’m doing. I need the script in the beginning, but I know that it’s just therapy for me and it has nothing to do with the painting.

DUNHAM: It’s good that you know that and that you can hold onto those two ideas at the same time.

MUSLIMOVA: I’m trying to be okay with uncertainty. I was reading your interview about starting work early on and all of the structure, when you had a desire to have no structure, but then of course structure comes in, [along with] parameters for your own self. And I know that when I started drawing, before I ever started painting, the only way that I could make that work is if I set up such strict parameters. But because of those strict parameters, I was able to actually have freedom in the work, until I felt like I was in a prison of my own making and then I had to change that around.

DUNHAM: I get that. I think that’s when I got the idea that I was going to work on paintings. It was really just what you said just then, that I couldn’t figure out what to do. I couldn’t find a point or a place to start, really. And none of the people I was close to when I was first trying to be an artist were really making paintings. I was very interested in the history of painting, so I thought, “Oh, flat rectangles, that’s great. I’m going to do flat rectangles.” And then within that I can do basically whatever.

MUSLIMOVA: Yeah, you have to put the body in the room, but you have to also identify the room. Somebody told me this many years ago, that if one is having a panic attack or something, you should map out and identify the clear architecture of the room in which you’re sitting, like a construction.

DUNHAM: [Laughs] I’ve had plenty, but I don’t know if that would’ve helped me.

Ebecho Muslimova, Fatebe Blow and Float, 2024, Sumi ink on paper, 15 3/4 x 18 3/4 in.

MUSLIMOVA: I’m realizing that in order to figure out the abyss of how to start and where to start, I had to build a parameter, literally, for those ideas to feel safe and to start whirling around.

DUNHAM: I was curious about the architectural spaces in those paintings. Like the one that’s up at the gallery in New York right now with that female Minotaur bathtub god character.

MUSLIMOVA: It’s Io, the one who’s turned into a heifer.

DUNHAM: Is that what it’s based on?

MUSLIMOVA: So that is an actual paper mache mask made by a sculptor in the ’30s for a production of Prometheus Bound. So that’s her mask and that figure in that painting is a Fatebe.

DUNHAM: Oh, wow. I saw it as a grotesque demigod of some kind.

MUSLIMOVA: I mean, there’s another two upstairs. I don’t know if you saw them, but things become a little satanic, and I don’t know why. Maybe because satanic times call for satanic images.

DUNHAM: And you’re working with the skeletons as a subject.

MUSLIMOVA: The skeletons appear and reappear because Fatebe is always alone, and I’m not interested in introducing another. But sometimes I do feel a need to have her interact with a thing, but not just an object. And since she’s stretched and strong and sort of defies physics, I needed another thing that is anonymous and bound to the human form because she’s so specific. She doesn’t have bones because she’s just a flat line, so I needed bones that adhere to real reality.

DUNHAM: It’s amazing to look at human skeletons.

MUSLIMOVA: I’ve never seen a skeleton in real life, but my parents had this skull that came from my uncle when he was in medical school, back in Dagestan. I think one of his friends dug up a grave or something crazy. But the skull had a name. He was just part of our family.

DUNHAM: That’s a lot for a kid to meditate on.

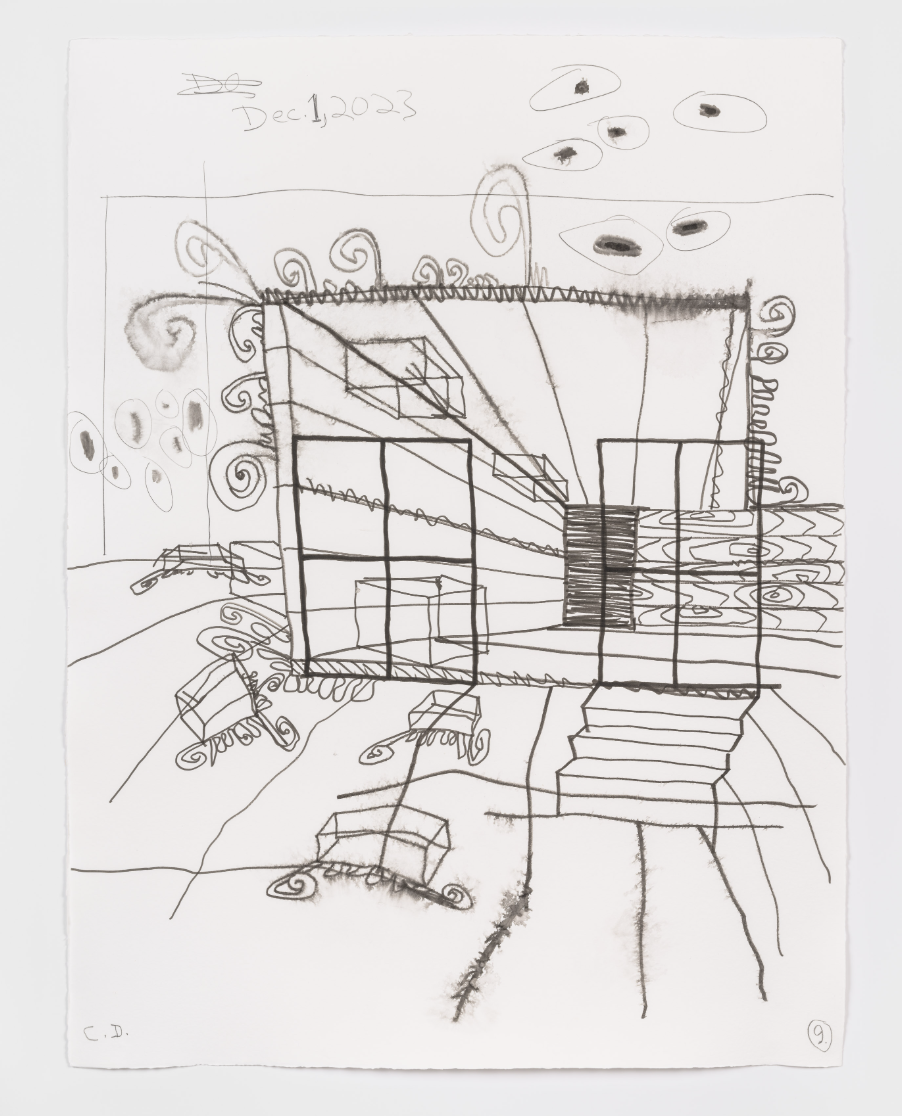

Carroll Dunham. Empty Spaces (9), 2023. Watercolour and graphite on paper, 40 × 30 in.

MUSLIMOVA: But I didn’t see anything to do with death. I think my first interaction with art was my dad showing me [Hieronymus] Bosch, the heaven and hell. And somehow, when I immigrated to America, that mixed in with the seductive line of Disney. So really it’s some mix of Bosch and Disney, which I think is still what happens.

DUNHAM: How old were you when you came over here?

MUSLIMOVA: I was almost seven. And I don’t care about cartoons or comics, none of that interests me, but the flat facade, the deep seduction of the Disney line really got me.

DUNHAM: For most of my working life, I felt similarly. When I first started having my paintings shown in galleries and they would get written about, people would always make some reference to cartooning, and it really drove me crazy because that wasn’t at all the way I was thinking. But I realized as things went along that I had just devoured cartoons when I was a child, like many of us. I was part of the generation of Zap Comix and I was interested in all of that psychedelic culture. It had a huge impact on me, but it felt like it was a completely separate part of me from the part that decided to be a serious artist and make paintings. I guess now I’ve given in to the fact that, somewhere in all the massive influences that are in the culture, the seductiveness of the golden age of cartoons is amazing.

MUSLIMOVA: Yeah. But it also was geopolitical for me. That’s what’s fun about painting, I guess, that it just keeps revealing your own false narratives or storylines that are then taken down and rebuilt. You’re not a stable subject. Like, we like painting and the career is fun, but what doesn’t keep me from getting bored is that each painting reveals something bigger than me, somehow.

DUNHAM: Yeah. I feel that more and more as time has gone on, because the thing that I found amazing is the way it keeps pulling me to the next thing. I don’t feel like I really have ideas. I feel like my whole artmaking practice always starts with drawings. But if I allow myself to receive it, it’s telling me what to do and bringing me to the next location, so to speak. Like, this thing I’m involved with now, the paintings that are at the gallery in London, I didn’t see that ahead of time. I only saw little glimpses of it in drawings or in aspects of paintings I was making before. It came out from the mist of all these different things pointing toward it. And then I had something to work on.

MUSLIMOVA: I mean, god forbid you see what you’re doing before it’s done, because then why do you need to do it?

Ebecho Muslimova. Fatebe Reap on Sow, 2023. Sumi ink and watercolor on paper. 15 3/4 x 18 3/4 in.

DUNHAM: Yeah. I mean, it’s fun for us to talk. I feel like there are quite a few overlaps in our attitude, but in the end, you’re making these things to be looked at, and if you could say what they are, you wouldn’t make them.

MUSLIMOVA: Also, to make things to be looked at, that’s a big part. We have a need to take the thing from inside and put it out there. You could get into psychoanalysis but, I mean, it’s a need. It’s not just a desire.

DUNHAM: It would be a lot simpler if it were only a desire because otherwise it wouldn’t be so unpleasant most of the time. I don’t know if you hear this from people who are having a very sincere reaction to something you’ve made and saying, “That looks like it was really fun to make.” I have to say, I don’t know if I’ve ever made anything that was fun to make.

MUSLIMOVA: But it’s nice to hold on to that glimmer. It’s fun to get the feeling of getting on the horse.

DUNHAM: I would agree with that. My consciousness splits into Dunham who’s working on the painting and this avatar that’s over here, who’s looking at me looking at the painting thinking, “Oh, this is actually pretty cool.” But it’s not always like that.

MUSLIMOVA: Yeah.

DUNHAM: What you just said a minute ago about what you’re experiencing internally, or wherever thoughts happen to get it out into some sort of object form, that’s a really mysterious process. And it’s what we go back to over and over again, putting something emotional or psychological or spiritual into the form of objects, and then other people look at them. That whole interaction is really deep and complicated, and one feels compelled to just go back over and over again to do it.

Carroll Dunham. Open Studio (4), 2024. Urethane, acrylic and graphite on linen. 74 x 60 in.

MUSLIMOVA: What you said about the split between you looking at yourself making the work, and then you being the work, as I’m understanding my character and the Fatebe character, it’s like, in the studio, I’m the boss and I’m the worker. I’m the boss exploiting the worker. But somehow, I’m putting her in these situations, and then she is compelling me to be put in a real-life situation where I’m working a ridiculous amount of time. It’s not the nicest relationship, but it’s a necessary one. And there is a dynamic between the two, but I literally needed to make another, to have this dance with that will justify me doing this to myself.

DUNHAM: It’s an amazing gift that your work gave you, to have this avatar. What you said is amazing, that you’re the boss and the exploited worker all at once.

MUSLIMOVA: In an eternal factory.

DUNHAM: Do you ever feel trapped by the character? I’ve had that happen to me in a couple of different phases of my work.

MUSLIMOVA: Me too, and I’ve actually tried to kill her off. But I don’t really do it any more because I’ve accepted that me and her are in the factory forever. But I’ve been like, “Okay, I’m going to do a final drawing. Enough with her.” And then I’m like, “Well, I should kill her off in the drawing, but I don’t want to hurt her.”

DUNHAM: Yeah, and you’re really just coming to a point of repetition.

MUSLIMOVA: Yeah, but that’s like hubris, thinking you have some sort of control. Like, “Oh, you think you could just walk away from this little dynamic?”

DUNHAM: I’ve gone through the whole cycle myself.

Content shared from www.interviewmagazine.com.