iStockphoto

Last June, Robert Redfield, former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), warned that a bird flu pandemic was coming. He said it was only “a question of when.” That “when” appears to be getting closer and closer.

In December, a person in Louisiana was hospitalized with a severe case of the bird flu, becoming the first known human H5N1 infection in the United States. It was also the first bird flu case in the United States ever linked to backyard, non-commercial poultry.

It was also reported in late December that 20 big cats at a sanctuary in Washington state had died from bird flu. NBC Chicago also reported this week that bird flu was the cause of the recent deaths of a Chilean flamingo and harbor seal at Lincoln Park Zoo. The zoo said it was “near certain” that the animals got bird flu from contact with an infected waterfowl.

In January, that patient in Louisiana died from the infection, making them the first known bird flu death in the United States.

So far, according to the CDC, there have been 67 confirmed human cases of bird flu in the United States. 38 cases have occurred in California, 11 in Washington, 10 in Colorado, two in Michigan, and one each in Iowa, Louisiana, Missouri, Oregon, Texas, and Wisconsin.

That number may go up in Michigan. Earlier this week, it was reported that Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (MDARD) officials had announced another outbreak of bird flu in Oakland County. There have been eight detections of the virus since mid-December. Six of which were in commercial production sites, while the other two were in backyard chicken flocks.

“It continues to be a really challenging disease to work through,” MDARD director Tim Boring told CBS Detroit. “We’re seeing impacts all across the country to this in a variety of different poultry species of whether it’s turkeys or broilers or egg layers.”

In addition to Redfield’s warning last year, Dr. Michael Gregor wrote a book in 2020 in which he warned that bird flu hitting the chicken farming industry could take out half of the world’s population.

Kimberly Dodd, dean of Michigan State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine and an expert in outbreak response for emerging infectious diseases, spoke to The Conversation this week about the risks H5N1 presents to families, pets and livestock.

“There are four types of influenza viruses: A, B, C and D, which are loosely defined by the species they can infect,” Dodd explained. “Avian influenza viruses are considered influenza A viruses. Interestingly, influenza D viruses are the ones that primarily infect cattle. But the current H5N1 circulating in dairy cattle is the same influenza A virus as seen in the ongoing outbreak in birds.

“This is of particular concern, as only influenza A viruses have been associated with human pandemics.”

“The current outbreak of HPAI H5N1 has been ongoing since 2021,” Dodd continued. “The outbreak is notable for its duration, wide geographic spread and unusual impact on nonpoultry species as well. It has caused significant illness and death in wild birds like ducks and geese, as well as mammals exposed to infected bird carcasses like cats and skunks.

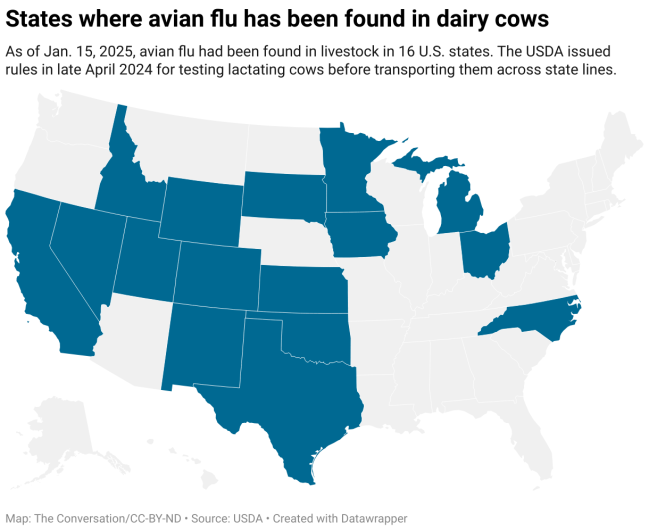

“However when the USDA unexpectedly confirmed that H5N1 was the cause of significant disease in dairy cattle in early 2024, it marked the first time that the virus was detected in U.S. dairy cattle.”

She added “experts are exploring the possibility that clothing, shoes, trucks, equipment and other items that have been contaminated with raw milk containing the virus can lead to inadvertent, and lethal, exposure for poultry.” This is an issue, she explains, because “prolonged circulation in cattle increases the risk of the virus adapting to mammals, including humans.”