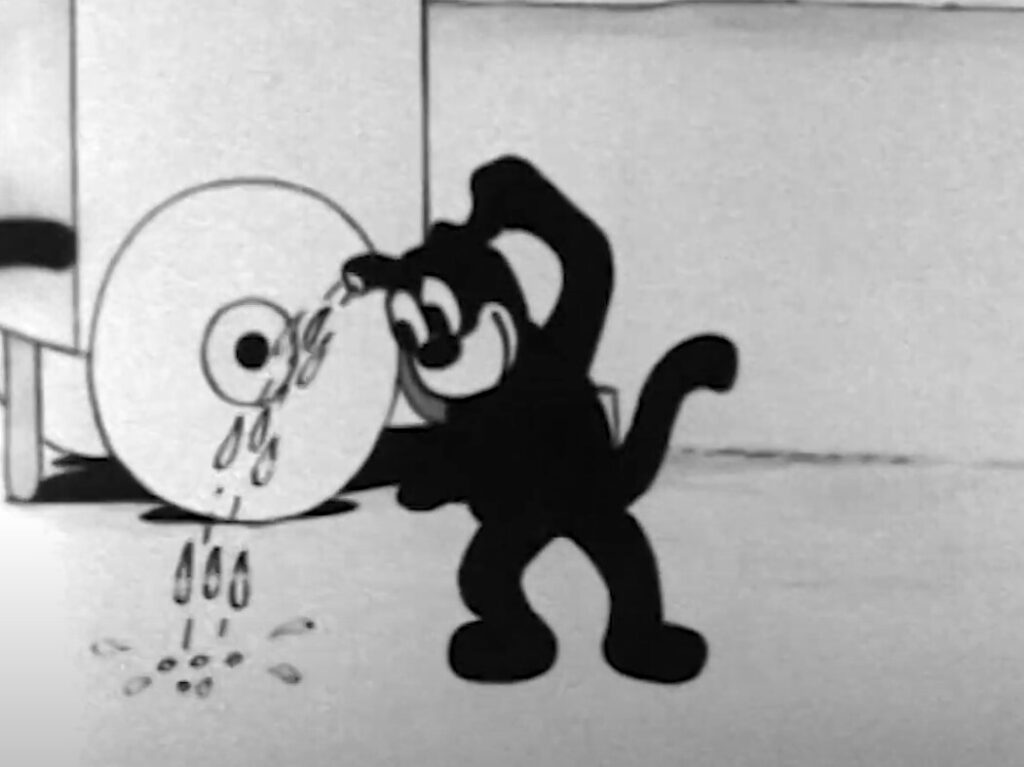

It’s time to talk about the smiling, black-bodied critter that had a massive effect on the future of animation, and it’s absolutely not Mickey Mouse.

Felix the Cat debuted years before Mickey Mouse, in the year 1919, with the cartoon Feline Follies as part of a Paramount collection that aired before feature films. He was created by Otto Messmer of Pat Sullivan Studios, a studio with a namesake who was all too happy to grab the credit and declare Felix his creation for decades. I don’t feel particularly pressed to give Sullivan the benefit of the doubt, though, given that he was seemingly a massive piece of shit.

Don’t Miss

Whatever the name on the tin, Felix became a beloved cartoon character by the entire nation. So much so that his appearances extended outside the screen. In fact, he received the honor of being the first cartoon character float ever launched at the Macy’s Day Parade — even if his balloon did immediately catch on fire.

With Felix a hit, Sullivan capitalized, probably barking drunken, slurred orders at Messmer to “draw the cat more.” From 1919 to 1921, Felix would star in 30 separate shorts, and Messmer likely laid the basis for a hell of a case of carpal tunnel. Come 1922, demand for Felix hadn’t fallen, but Sullivan needed a new distributor, and found one in Margaret J. Winkler. The cats kept coming, and over the next four years, 50 more Felix shorts were released, with Felix’s appearance moving to the more rounded, iconic cartoon look.

Sullivan, ever the image of business acumen and foresight, undid his deal with Winkler in 1925, leaving her in need of another animator. She found one, and you might not know her name, but you definitely know his: Walt Disney. How did Winkler know Disney was up to the task of filling Felix’s paws? Well, she had pretty direct proof: a blatant knockoff of Felix that Disney had already churned out, called “Julius the Cat.”

Of course, this was the late 1920s, and suing Disney wasn’t yet a pursuit about as fruitful as milking a bull, so Winkler balked at producing basically “Not Felix” right after the split. Instead, she had Disney cook up a very different, completely dissimilar character called Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. He was different from Felix, you see, because he was a rabbit, and lucky. If Sullivan managed to notice the resemblance through his gin-soaked eyes, he’d have realized that Oswald’s ears were far too long to be based on anyone.

Oswald made his debut in a short called Trolley Troubles in 1927, and luckily enough, their big bet on “Felix With Funny Ears” also resonated. Unfortunately, Disney didn’t get to ride the Oswald treasure trolley for long, and the rabbit was scooped out from under him by Universal only a year later in 1928. Full of what feels like hypocritical rage over the theft of his character, Disney returned to his roots: changing existing character’s ears, and with triangle and oval already taken, he settled on circles, creating a mouse named Mickey.

Mickey Mouse turned out to be a quite successful character for Disney, in that his global recognition to this day hovers somewhere around the level of “Jesus.”

So where was Felix while this species-swapped impostor cashed his ticket to endless fame? Well, Disney happened to debut Mickey at the perfect time, along with the inclusion of sound in animated film. Felix, rickety 10-year-old cat that he was, could never quite get the hang of talkies, while Mickey was an immediate audiovisual success with Steamboat Willie. Felix remained successful on some level for many years, especially under the guidance of new producer Joe Oriolo, who also finally gave Messmer the creator’s credit he deserved, but was soundly lapped by his bastard rodent offspring at every turn.

By the turn of the 21st century, in what has to be a stinging insult, people unfamiliar with Felix probably saw his face and thought he was a knockoff Mickey instead of the other way around.

All of which is to say, if you call yourself an animation lover, you should salute Felix for paving the way for much of modern animation. The animation monolith that is Disney will never (and probably legally can’t) admit it, but Felix is interwoven into their foundation as well.

Both, of course, are built off of racist minstrel stereotypes, because this is America and our history is a tower of people climbing to success using those less fortunate’s faces as a foothold, all the way down. We’ll leave that subject for a different article, though.