In an office park in Hawthorne, a robot built by rocket scientists is making pizza.

Inside the machine, a box roughly the size of a cargo van, a metal claw plucks a ball of premade dough out of its refrigerated chamber. A press then smashes the dough into a 12-inch disc. On a conveyor belt, a nozzle spits out sauce, dispensers shake cheese and toppings on top, then a robotic lift carries the raw pie to one of four 900-degree deck ovens. Cameras and sensors track the progress from step to step, making tiny adjustments along the way. In 45 seconds, a finished pizza pops out.

It tastes pretty good. It costs just $7 to order (or as much as $10, depending on toppings). And with slim labor costs and a chef that never eats, sleeps, or takes a break, the team behind Stellar Pizza think they can take a bite out of the country’s $45-billion pizza market — or at least the part of the pie that’s dominated by high-volume, low-cost chains.

Benson Tsai started the company in 2019, after leaving a job designing batteries for spacecraft and satellites at SpaceX, the Elon Musk-helmed rocket company around the corner from Stellar’s headquarters.

A robotic arm picks up a dough ball during a demonstration of pizza making at Stellar Pizza’s headquarters in Hawthorne.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

He convinced a couple dozen fellow engineers to join him, raised $9 million in funding and spent the last three years honing the Stellar recipe and building its pizza machine.

Now they’re raising a second round of funding to build out a fleet of finished robots, each of which can fit in the back of a bright red 16-foot box truck to travel to stadiums, college campuses and other customer-dense locations. Orders will be taken via a smartphone app; the few humans involved will be there to drive the truck, assemble the boxes and distribute pies.

Stellar is not alone in the food robot field. A number of restaurant automation companies have been building labor-saving devices in recent years: delivery robots that trundle across sidewalks, waitstaff robots that roomba between tables with dishes on their heads, and robot arms that can operate fryolators are all finding a toehold in the industry.

But pizza has attracted more mechanized attention than most other foods.

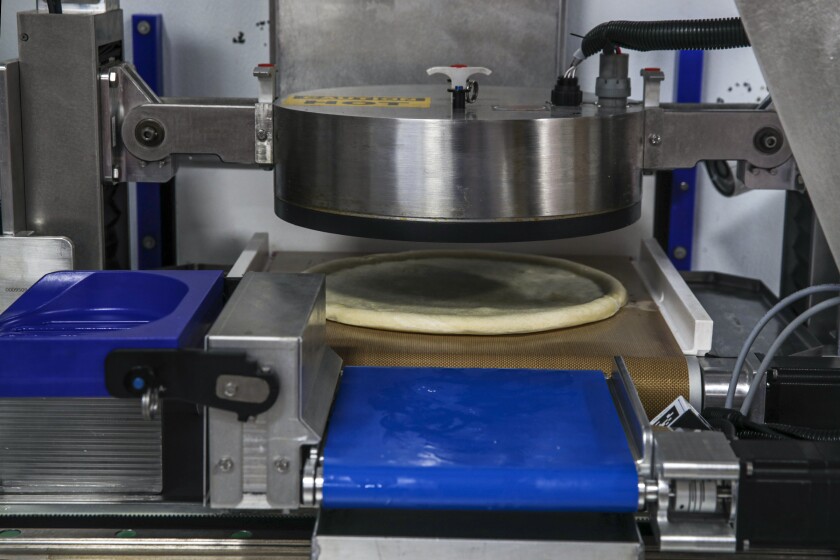

The dough ball is smashed into a 12-inch disc (with crust)

(Irfan Khan/Los Angeles Times)

“Pizza is a massive opportunity, and so a lot of players are getting into the space,” said Chris Albrecht, an industry expert who writes the food automation newsletter OttOmate. “The universal appeal of pizza is what makes it the tip of the spear for startups looking to get into food automation.”

Because humans — and especially Americans — eat a lot of pizza. The global pizza market is estimated at about $130 billion in sales, according to Pizza Magazine’s 2022 Pizza Power Report, and more than a third of that business is in the U.S., where Americans spent about $45 billion on pizza in 2021.

That demand was met by 75,117 pizza restaurants nationwide in 2021, with Domino’s leading the industry in sales. With franchises and company-owned stores, it has 6,597 locations in the U.S. and more than 19,000 worldwide, according to its latest financial filings.

It takes an army of human workers to make all that dough. Hundreds of thousands of people work at Domino’s locations, and difficulty hiring in the last year has cut into the chain’s delivery business — on a corporate earnings call in April, Domino’s announced that it would continue to offer customers $3 in store credit to pick up their own pizza instead of ordering delivery, a pandemic-era promotion.

Arik Jenkins, left, and Ty Kuo test Stellar’s pizza-making robot.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

This extra-large market facing labor constraints has inspired a few different robot approaches: pizza vending machines, standalone robotic pizza kitchens and robots that slot into existing restaurant kitchens.

None of the categories has a clear winner — yet — though a handful are currently in operation. In the vending market, L.A.’s Basil Street Cafe had deployed 12 vending machines that would cook frozen pizzas before shutting down in April. Pasadena’s Wavemaker Labs, the parent company of the fry-kitchen Flippy robot, is building a pizza vending machine called Piestro, which cooks pizzas fresh, and has announced a co-branding deal with 800 Degrees Pizza.

A handful of other companies, such as Seattle’s Picnic and the Bay Area’s XRobotics, make machines designed to be installed in standard restaurant kitchens, or just placed on a countertop, that can automatically prep a pizza with sauce and toppings; a human can then pop the assembled pie in the oven.

The best-funded robot-pizza startup to date, Zume Pizza, imploded in early 2020 after absorbing $375 million in funding from Softbank Vision Fund, the same venture capital firm that plowed billions into WeWork before its collapse. But Albrecht argues that calling Zume’s setup a pizza robot was always a stretch.

“Zume wasn’t a robot company,” Albrecht said, but rather a company that pitched a big-data approach to predicting pizza demand to efficiently place its trucks. The process was never fully automated, and used off-the-shelf robotic arms to spread sauce and insert pizzas into the oven while humans applied toppings and shaped the dough.

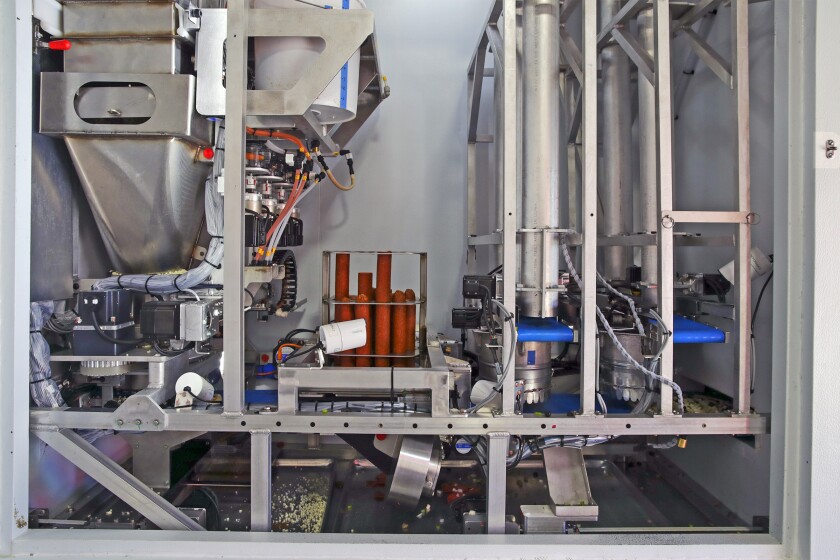

The toppings assembly line inside Stellar’s pizza robot.

(Irfan Khan/Los Angeles Times)

Stellar’s machine is closer to a miniature factory than a kitchen with robot chefs on the line — and Tsai plans to take a bigger swing at the market than many competitors. Instead of trying to fill the convenience niche of a vending machine or target the restaurant industry with a plug-and-play pizzabot, he wants to turn Stellar into a name brand on par with Domino’s, Papa John’s or Pizza Hut, and win the day through the power of superior economics.

“Our vehicle build cost is on the same order of magnitude as building out a Domino’s store,” Tsai said. He declined to give specifics, but said that the cost was in the low six figures. Domino’s franchise agreement estimates that, minus franchise fees, insurance, supplies and rent, opening a new location costs between $115,000 and $480,000 to build out.

With lower overhead compared with a store staffed by humans, Tsai says Stellar can drop prices but still maintain the fat profit margins enjoyed by pizza chains. Company-owned Domino’s locations had profit margins of 21% in 2021, according to the company’s annual report, even after 30% of revenue was eaten up by labor costs.

Stellar plans to begin rolling out its trucks to events in L.A. later this summer, once it gets its final approval the health department. In the meantime, the company is hosting pop-up events for its newsletter subscribers at its Hawthorne headquarters.

A pizza with toppings comes off the conveyor belt and onto the platform that will convey it into a deck over inside Stellar’s pizza machine.

(Irfan Khan/Los Angeles Times)

Stellar’s planned price range of $7 to $10 for a 12-inch pie, depending on toppings, is comparable with pricing by Domino’s or Pizza Hut, though the chains often are lower with coupon offers. But if the big incumbents start to go cheaper, Tsai said he’d “welcome a price war.”

But first, he needs customers. The pizza itself is the product of two years of fine-tuning the recipe for both flavor and ease of automation. The final product has a thin crust, a mildly sweet sauce and can be ordered as a plain cheese pie, pepperoni, meatball, or with veggies (diced onions, green peppers, or olives).

Tsai started Stellar as a longtime pizza eater, but first-time pizza entrepreneur — he said that the only American food allowed in his Taiwanese-American childhood home in Hacienda Heights was pizza from the local pie shop. “I don’t wanna rag on it, but it was called The World’s Best Pizza,” Tsai said. “I really liked it, but I actually don’t think it’s the world’s best pizza.”

Tsai had started his own company before working at SpaceX, and after five years at the rocket company, he wanted to set out on his own again — and focus on food.

His first thought was a boba robot. “I’m from Taiwan,” Tsai says. “I wanted a boba vending machine.”

But a little market research revealed that most Americans are still unfamiliar with the milk tea-tapioca ball combo. “Going to Missouri and trying to teach people how to drink this like, chewy button nugget” didn’t seem like a good business model for his first startup, Tsai said.

As a final step, the pizza gets cooked at around 900 degrees.

(Irfan Khan/Los Angeles Times)

Once he landed on the idea for Stellar, he and his team dove into pizza science, reading academic papers from Italian universities outlining the mathematical models of heat transfer from ovens to pizza dough, and theorizing on the outer limits of pizza cooking speed. “Given my background in chemical engineering, I thought it was amazing,” Tsai said.

Then the company brought in Noel Brohner, the acclaimed pizza consultant behind Slow Rise Pizza Co., who’s worked with elite L.A. chefs such as Evan Funke and Ori Menashe (of Felix Trattoria and Bestia, respectively), bigwigs such as Tom Hanks and Bob Iger who want to perfect their at-home pizza game, and big companies such as Google and Mod Pizza to fine-tune their recipes.

“When I started working with them, they had a warehouse with nothing in it. I have a better kitchen in my apartment in Santa Monica now,” Brohner said. But when he first tried the pie that Tsai and his colleagues had cooked up based on their own research, “I was really impressed, and kind of shocked that a couple of rocket engineers could do so well for themselves even before I got brought in.”

The dough presented the biggest challenges for automation, being a sticky matrix of yeast, water, and flour that shifts with time, temperature and humidity. Stellar makes its dough at its headquarters, then loads dough balls into the machine’s refrigerator for a day’s output. Typically, Brohner said, the mutability of dough requires human expertise to handle, roll out, and troubleshoot. “But if you’ve got lasers and video and photo and thermopens” sensing changes on the fly, as in Stellar’s machine, he said “you can actually do a lot.”

The finished pizza emerges from the oven.

(Irfan Khan/Los Angeles Times)

Brohner doesn’t see Stellar as a threat to the high-end handmade pizza market, but a chance to get higher-quality pizza to the masses. “What I love about it is instead of having a labor cost close to 20, 30, even 40%, it’s closer to 10%” Brohner said. “So what they’re able to do is use much higher-quality ingredients” while keeping costs competitive with the big chains.

In an economy defined by a drum-tight labor market and growing inflation, Stellar is betting that combo will be almost as appealing as cheese and tomato sauce.