GEORGE Mycock had decided he was going to kill himself. He had been locked away in his room at Durham University for several weeks, full of shame, bingeing on junk food.

“Every couple of months, I hid in my room for up to two weeks, ordering food or sneaking out at night to a shop,” he recalls.

“I knew it couldn’t continue, so I planned killing myself. I had the date in mind and thought about how I was going to do it.”

George, from Stoke-on-Trent, could hide this habit because he was popular, handsome, outgoing, and hence.

None of his family or friends knew the depths of his despair.

They had no clue that an obsession with attaining the perfect physique had morphed into a self-destructive spiral of compulsive training, followed by binge-eating two large pizzas, a box of fried chicken, and two tubs of Ben & Jerry’s.

Though he didn’t know it then, George, now 28, was struggling with the often-misunderstood body dysmorphic disorder (BDD).

The mental health condition sees sufferers develop a preoccupation with an imagined or slight defect in their appearance, which impacts the normal functioning of their lives.

It’s estimated that one in 50 people in the UK have some form of BDD, with young women aged 17-19 the most affected.

However, the scales appear to be tipping. A 2021 study found that 54% of men displayed signs of BDD, compared to 49% of women.

The number of men, particularly young men, gripped by body dysmorphic disorder continues to rise

Dr. William Shanahan

That figure appears to be rising rapidly, with one US study reporting that the percentage of men dissatisfied with their overall appearance has nearly tripled in the past 25 years.

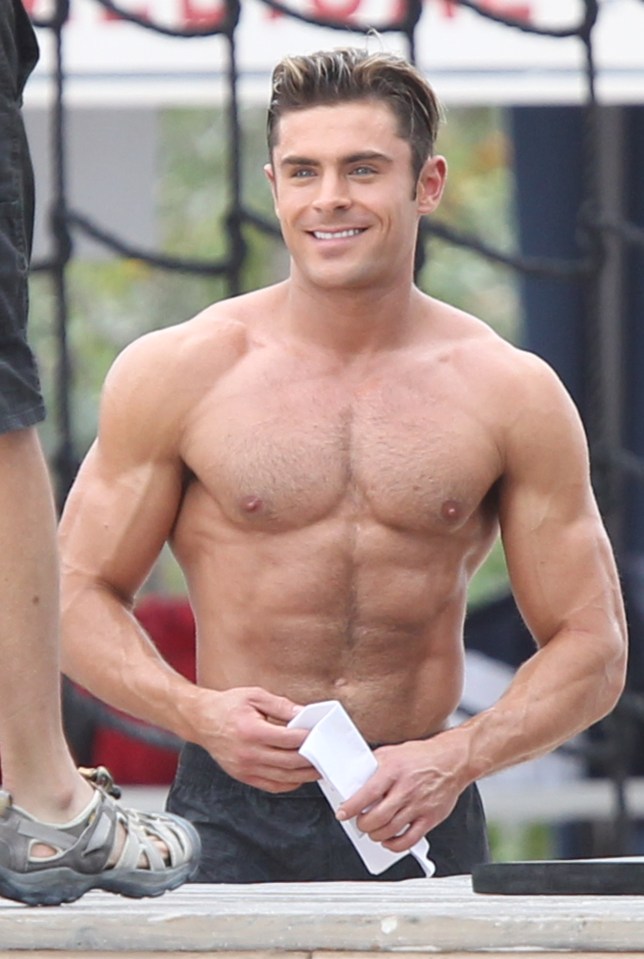

Experts say this is fuelled by images of muscle-bound bodies that men are being bombarded with via TV – on programmes such as Love Island and Gladiators – social media influencers, and bulked-up Hollywood actors.

A-lister Zac Efron has openly talked about his struggles with body image and revealed he took so many diuretics to get into shape for the 2017 movie Baywatch that he fell into “a pretty bad depression.”

“The number of men, particularly young men, gripped by body dysmorphic disorder continues to rise,” says Dr. William Shanahan, clinical director of addictions at Priory Hospital Roehampton in south-west London.

Help for mental health

If you, or anyone you know, needs help dealing with mental health problems, the following organisations provide support.

The following are free to contact and confidential:

Mind, www.mind.org, provide information about types of mental health problems and where to get help for them. Email info@mind.org.uk or call the infoline on 0300 123 3393 (UK landline calls are charged at local rates, and charges from mobile phones will vary).

YoungMinds run a free, confidential parents helpline on 0808 802 5544 for parents or carers worried about how a child or young person is feeling or behaving. The website has a chat option too.

Rethink Mental Illness, www.rethink.org, gives advice and information service offers practical advice on a wide range of topics such as The Mental Health Act, social care, welfare benefits, and carers rights. Use its website or call 0300 5000 927 (calls are charged at your local rate).

Heads Together, www.headstogether.org.uk, is the a mental health initiative spearheaded by The Royal Foundation of The Prince and Princess of Wales.

He explains: “We’ve become much more conscious in the UK about the widespread media depiction of unattainable body images for women, but we need to raise more awareness of body dysmorphia for young men.

The increasingly lean and muscular body type displayed in the media rarely exists in nature.”

The type of BDD that George suffered from – muscle dysmorphia (MD), also known as “bigorexia,” typified by an intense preoccupation with insufficient muscularity – is also on the rise. In the UK, the BDD Foundation estimates that one in 10 male gym-goers have it, and that figure is rising.

Sufferers are at high risk of steroid abuse and eating disorders and struggle to maintain relationships because of the disabling anxiety and shame, while 50% have attempted suicide at least once.

“For young men, the disorder is intertwined with rising rates of anabolic steroid addiction, as people turn to drug misuse to try to ease their anxieties,” says Dr. Shanahan.

“We’re supporting more and more patients affected by this issue in our services across the country and are increasingly concerned by the ongoing trend.”

‘Whenever I binge ate, I felt so much shame that I would hide away and lock myself in my room’

The seeds of George’s condition were sown in childhood. A keen rugby player, he was forced to stop playing at 13 after breaking his spine at a game.

He spent the next year in and out of hospital, started comfort eating, and put on weight.

George says: “This was the first time I remember feeling ashamed of my body.

“Eventually, I returned to school weighing around 6-7st more.

“Not many people pointed out my weight gain, but it was obvious to my hyper-aware mind that they were treating me differently.

“I started to run a lot, and I barely ate anything.

“I would run for an hour each day and go to the gym.

“I began to lose a lot of weight, and I got a lot of compliments.”

The compliments drove George to push himself even further, eating less and training more, which he managed to hide from his family.

Whenever I binge ate, I felt so much shame, I would lock myself in my room. I’d feel so horrendous about myself, like I’d failed.

George Mycock

He explains: “I started restricting food severely at around 15 or 16 years old, though the thought that my symptoms could be an eating disorder didn’t cross my mind.

“On social media, every man in the fitness industry has a six-pack, big shoulders, big arms, veins popping.

“I thought: ‘OK, this is what I’m supposed to be like. I don’t need to get thinner; I need to be more muscular.’

“I was scared of gaining body fat, so I’d eat and then do excessive exercise or make myself sick.

“Later, when I started university, I stopped the purging and would have these uncontrollable binges.

“Whenever I binge ate, I felt so much shame, I would lock myself in my room. I’d feel so horrendous about myself, like I’d failed,” he says.

Outwardly, George had a build most men would kill for.

READ MORE MEN’S HEALTH STORIES

But looking in the mirror, he saw something different. “I zoomed in on body parts I thought were not big enough.

I analysed every aspect of my physique. It was exhausting. I can remember going to lectures and being so paranoid, trying to hide certain parts of my stomach or whatever it was that I felt wasn’t right. I was constantly scared and ashamed.

“I always needed a girlfriend because I saw that as further proof of my masculinity, but I was incredibly insecure,” he says.

Eventually, the psychological and physical stress became overwhelming, and by 2018, George decided to end his life.

Thankfully, a friend intervened. “She knocked on the door and called out,” he recalls.

“Something in me told me to answer.

“She could see something was wrong and I broke down and told her how horrible I felt. I didn’t tell her I was planning to end my life, but I told her how hopeless I felt and she encouraged me to speak to my family and get help.

“When I confided in my parents, they weren’t always sure how to handle it.

“The moments I remember most fondly were when they would just sit with me and say that they were going to be there for me, no matter what.

“I can’t express enough how much that can help someone in my situation.”

George was prescribed antidepressants and started counselling, but despite having all the symptoms of MD and BDD, he’s never been diagnosed.

“This is not unusual – getting a diagnosis is a lottery, and the condition is still not fully understood.

Priya Tew is a registered dietician and spokesperson for the British Dietetic Association.

She has seen a rise in cases of men with BDD at her practice in the last few years and says that cases are likely to be under-reported.

“It has become more prevalent, but a lot of men don’t see it as a problem or would not necessarily identify it as important enough to see the GP about,” she says.

Priya believes social media is one of the main factors fuelling it.

She adds: “People are bombarded with content, and if you show an interest, the algorithm feeds you more of the same.

“TikTok is full of personal trainers walking around with their tops off, showing their rippling six-packs.

“It’s almost the norm. It creates the illusion that if you don’t look like that, there’s something wrong with you.”

Worryingly, research has found evidence of a “promuscularity” community online, much like the pro-ana community that glorifies eating disorders.

The websites that form this group reinforce and encourage rigid dietary practices and exercise rules, and they extol the benefits of muscularity.

The damaging effects include low self-esteem, social isolation, disordered eating, strained relationships, risk of injury, and obsessive behaviour.

Priya says: “It starts to take over life in an extreme way.”

Mother-of-two Anna* has seen this only too well.

Her 16-year-old son Ben* goes to the gym daily.

His Instagram feed is full of male fitness influencers; he buys protein powders, bars, and supplements and is starting to hide some of his eating habits.

Anna had heard of BDD, though she believed it only affected girls – but now she fears her son is developing it, and MD in particular.

‘Honestly, the biggest support I got was from my friends at the gym’

Anna says: “Ben was overweight when he was younger.

“He liked sweets, and he was never an active child, preferring gaming to sport.

“He wasn’t interested in his appearance until he was around 14.

“He naturally lost weight when he had a growth spurt, and people commented that he looked well.

“He started to exercise at home, then got ideas and programmes from YouTube and social media.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s that, no matter how lost you feel – even if you don’t know who you are, who you could be, or what that means – things will get better.

George Mycock

“At first, it all seemed healthy.”

Initially, when Ben skipped the odd dessert, Anna was unconcerned. But then he started leaving all carbs at mealtimes. “He got defensive and said potatoes and pasta were fattening.

“Then he started buying protein shakes and supplements because he said people on social media recommended them for muscle building.

“When I pointed out he needed a balanced diet, he said he didn’t want to get fat again.

“He also started spending more time at the gym and now goes every day, sometimes before school and after, and at the weekend.

“During summer, we had planned trips to the cinema, which he wasn’t bothered about.

“He only hangs around with friends who go to the gym.

“I don’t want to discourage him from being healthy, but I worry that he’s crossed a line,” she says.

“His dad and I have spoken to him, and we’re both concerned.

“His dad thinks it’s less of a problem, but I wouldn’t want him to get any more obsessive. I’m hoping it’s a fad he’ll grow out of.”

Priya explains that, for worried parents, the key is to keep talking.

She says: “It’s about trying to work out what’s going on in their life and what is driving this behaviour.

“It’s important the child knows they are loved, and if a parent is concerned, get educated about the condition and get support.”

George turned his experiences into something positive and now runs MyoMinds, one of the few organisations in the UK specialising in helping MD and BDD sufferers, with a community where people can get information, advice, and share experiences.

“I consult on several different clinical and research projects, and when I speak to clinicians, one of the things that always comes up is the preconception that exercise and a muscular body is synonymous with health,” George says.

“Honestly, the biggest support I got was from my friends in the gym.

“When I started being honest with them and talking to them, I realised how many of them had similar experiences and thoughts.”

Testament to the fact that recovery is possible, George believes opening up is the first step.

He says: “If there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s that, no matter how lost you feel – even if you don’t know who you are, who you could be, or what that means – things will get better.”

For advice and support in dealing with BDD, visit Mind.org.uk.

*Names have been changed. Photography: Getty Images, Splash, The Times, The Sunday Times. Sources: **Better ***BMJ