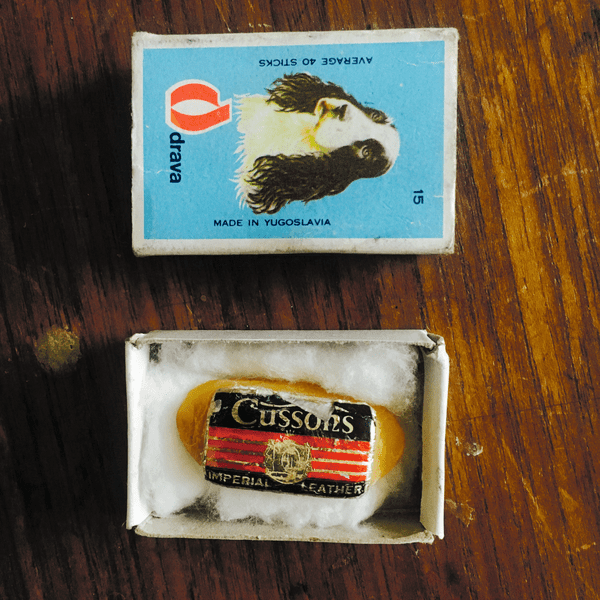

The first memoir from the former lead singer of Pulp would have been better titled A History of Jarvis in 100 Objects. That’s what it is: an illustrated guide to the things that make Cocker who he is. He doesn’t appear in many of the photos; the great majority show his collection of ephemera: a 20-year-old pack of Wrigley’s Extra gum, a fragment of Imperial Leather soap with its old-style label still attached. That’s him in a nutshell: driven by a lifelong love of the everyday, perceiving romance and poignance in items that others chuck out. It isn’t wrong to say that without this sensibility, there would have been no Pulp, whom he led until 2013, no many-tentacled solo career and consequently no national treasure status.

This isn’t the story of his time at the top. The penultimate object in the book is an acceptance letter, dated 1988, from Central Saint Martins School of Art and Design in London. It was while studying film and video there that he “ran slap bang into the subject matter of The Song That Made My Name”, which is the book’s only reference to Common Pe(Please let there be a sequel covering those years.)ople and the starry decade that followed.

Good Pop, Bad Pop ambles through the 25 years before Saint Martins, tracking Cocker’s worldview as it takes shape in his home city of Sheffield. It opens in the present day, as he’s clearing out the loft of his London house. There is a lot of stuff in there, and each item has a story. His task is to decide whether to keep each thing or “cob” it (throw it out). Mulling over these ancient treasures puts him in philosophical mood, and the book soon expands into both an autobiography and a treatise on pop.

Good pop is anything – not necessarily music related – that democratises culture, from jumble sales to Penguin paperbacks. (Jumbles were nirvana: not only did they help Cocker find his own style – see the polyester BHS shirt on page 29 – they also served tea and cake. It was, he writes mistily, “a complete day out”.) Bad pop, represented by a cardboard joke version of Margaret Thatcher’s handbag that he bought at WH Smith in 1979 (cob), uses good pop’s informality and catchy slogans to manipulate the public. Alongside all that is Cocker’s hope that by revealing his creative pathway, he’ll induce readers to find their own.

That generosity is a hallmark of the book. If pop could save a bespectacled beanpole who found his name so embarrassing he briefly called himself John, it might save others. Cocker’s thoughtful and very funny ruminations make it seem possible. Although these events happened at a time when aspiring bands could support themselves with supplementary benefit, and every community had a library, at least his enthusiasm is transferrable.

It is the unglamorous, character-shaping details that fill the pages. There’s his childhood in a matriarchal home, and his aversion to change – the reason he saves things that still have their 1980s packaging, such as the Imperial Leather (keep). There’s an adolescence divided between punk gigs, jumble sales and trying to learn what “masturbation” meant. A ripped copy of The Fantastic Dirty Joke Book (keep) didn’t explain it, so he turned to the dictionary and learned it was “self-abuse”. For a time, he assumed it entailed “walking around shouting at yourself ‘shithead!’ or ‘fart!”’

At the same time, he was formulating what he called The Pulp Master Plan. A school exercise book (keep) contains the blueprint for the band he wanted to form. They would wear Oxfam blazers and “rancid ties”, the music would be “fairly conventional but slightly off-beat pop songs”, and they would “[learn] about the world by looking at what it threw away. By what it deemed ‘worthless’”.

By the time Cocker was in his early 20s, the Pulp aesthetic was fully formed. “Pop was empowerment,” he writes. “Pop was made to satisfy primal desires.” He moved into his own idea of Andy Warhol’s Factory, an unheated industrial building through which passed many of Sheffield’s alternative types. He spent his time there on the dole, writing songs and tending his collection of plastic carrier bags, which he used every day, and still does now. But in 1985, trying to impress a girl, he fell from a window, and spent six weeks in hospital. It brought about an epiphany: “The scales had fallen from my eyes. I now realised that I’d been surrounded by inspiration all along.” His songwriting changed, and with it, his life. How? It’s worth buying this terrific book to find out.