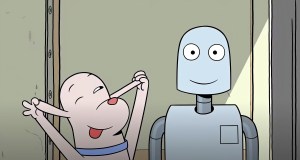

Director Pablo Berger never thought he’d earn his first Oscar nomination for an animated feature, mostly because he never thought he’d direct animation. That is, until one morning, when he was looking through his vast library of books and decided to read Sara Varon’s 2007 graphic novel Robot Dreams, the bittersweet story of the friendship between a dog and a robot. As soon as he put down the book, the multiple Goya-winning Spaniard knew he’d found his next film. That chance reading led to a premiere at Cannes, multiple awards and an Oscar nomination — all for a movie that hasn’t even seen its main U.S. release yet.

DEADLINE: How did you first encounter the graphic novel for Robot Dreams?

PABLO BERGER: I collect books with no words. When my daughter was two or three, I wanted to share the experience of my love of books, so I could read the wordless books with her and she could read them by herself. So, I just started this collection, and it has become my dearest collection of hundreds of books that have no words.

I got Robot Dreams in 2010 and I loved it. I thought it was fantastic and unique and when I got to the end of the book, I was deeply moved. And when I’m talking about deeply moved, I was in tears. I know this could sound a little bit too much, but I was visualizing the film while I was reading it. If this book has moved me this deeply, I thought maybe I should just make this film. I never in my life thought about making an animated film. I come from live-action. This is my fourth film. I love animation as an audience, as a cinephile, but never in my life, not even once, until I read this book and the end moved me so deeply.

Robot Dreams

Neon/Everett Collection

DEADLINE: What about the book resonated with you?

BERGER: The fact that it’s wordless and that it’s a very simple story. I knew that when I was reading to make the film, I thought about friends that I lost. You know, when you lose a friend, sometimes it’s even more difficult than when your heart gets broken from a love story, because it’s more difficult to understand why this friendship faded or broke. And I also thought about people that are not in my life anymore. In a way, I made this film as a love letter to all the people that have been part of my life that are not with me anymore.

DEADLINE: Tell me about meeting Sara Varon, the creator of the graphic novel.

BERGER: Once I decided that this would be my next film, it was like providence. I got an email from the Chicago Film Festival inviting me to be on the jury for the official selection, and suddenly I thought, what a great time to have a layover in New York, meet Sara and propose to her that I wanted to make a film.

We met on the Lower East Side in a coffee shop, and I just bluntly told her, “I love your book. I want to make a 2D film of Robot Dreams.” And she was like, “Oh my god.” She told me that in 2008 she was approached by a big animation studio to make a 3D film, but at the end, this didn’t move on. And she was really happy that I was coming from Europe and proposing to make a 2D film of her book, so she really felt that the adaptation of her graphic novel was in good hands. So, she said, “I made the graphic novel, and I’ll give you carte blanche to make the film.”

DEADLINE: I can’t imagine this film in 3D at all.

BERGER: Me either. I love comics and I wanted this movie, among other things, to be a love letter to comics and to graphic novels. So that’s why I wanted to respect the ink and paint of the style, the flat colors, this ligne claire of old comic books. Something for me that was extremely important was to have everything in focus. When you read a comic book, everything is in focus, and in cinema you definitely play with the depth of field. But I wanted to have a deep-focus animated film because we wanted every single composition to be powerful, and the camera didn’t have to move too much unless it was absolutely necessary. I put some kind of restrictions to the animation director and to the team, and also when I was making the storyboards. So, when comic lovers watch this film, I want them to imagine they’re really reading a comic book, but it’s moving images.

DEADLINE: Why did you choose to set the film in New York City?

BERGER: In the graphic novel, it’s not a defined city because you don’t have any landmarks. For me, when I started adapting the script, I told Sara, “I am a New Yorker at heart. I lived 10 years in New York, and I want the protagonist of Robot Dreams to be a dog in New York City. I want it to be my love letter to the New York that I experienced.”

Definitely, there’s a certain nostalgia in this film. It’s in New York before the globalization, before internet, before mobile phones. The New York that I lived in, when New York was the cultural or the economical capital of the world, you know?

DEADLINE: Since there’s no dialogue, music and sound play a crucial role here. How did you create the soundscapes of the city?

BERGER: The thing is that this film is dialogue-free. It’s not a silent film. It is very important, as you said, that it’s dialogue-free, because the sound design of this film is the most complex of all my films. The sound designer, Fabiola Ordoyo, and her team recreated what New York sounded like in the ’80s, and she really had to dig into old sound libraries.

I lived in New York for years and something that can identify New York is that it’s extremely noisy and full of all kind of alarms, sirens and also the sound of the cars of the time. It was very, very important that the audience, when they come to see Robot Dreams in the cinema, not only have a visual experience, but also sensorial.

That’s the kind of films that I want to make. I want to make sensorial experiences. Robot Dreams, we can even say it’s a musical, or we can even say the audience will come to the cinema and travel in time to New York in the ’80s. And that was our goal, that when the audience comes to the cinema, they really can forget about all their concerns, and they can just get into the screen and be Robot and Dog.

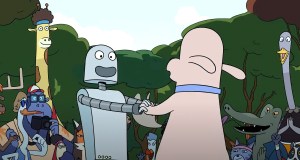

Robot Dreams

Neon/Everett Collection

DEADLINE: Where did the idea come from to use Earth, Wind & Fire’s “September”?

BERGER: It was very early on in the first draft of the script, when I was just doing the outline and the idea came in a very simple way. The film starts in September and it’s one year in the life of Robot and Dog. I also needed a song that could be danced to in a roller dance, because it was very important from the beginning that they be roller dancing in Central Park. So, I needed a song that is funky and has a beat, and it was the ’80s, so it had to be like the disco era. I think in the late ’70s and early ’80s, and even now 40 years later, “September” is still one of those songs that is contagious.

I think all relationships have a song, or a musical theme. And the moment I found it, it became another key element in the story, because it’s a theme that appears many times in the film in many different versions. As long as they hear “September”, we know that they’re connected.

And the amazing thing about this song that I didn’t realize when I started the production, is that in the first three words of the lyrics is the main theme of the film. The song starts, “Do you remember?” That’s something that I really want to talk about, how memory can help us to overcome the pain of a breakup or when you get distance from somebody that you love. It was very important that that element in the lyrics appears very clear.

DEADLINE: When I was watching it, I connected with pretty much every character. You see a bit of yourself in every character, and you also just feel for them. I mean, that first dream sequence for Robot where the bunnies come… That was heartbreaking.

BERGER: As a film director from live-action, I wanted to bring amazing performances to animation. I wanted to make truthful, emotional performances that were three-dimensional. For me, less is more in cinema.

It’s very common in animation that the animated characters overact instead of moving a little slower or moving the eyes less. In live action, I’m always next to the camera looking at the actor’s eyes. So, when I was working with the animators for two years, my obsession was to look at the eyes of Robot and Dog and every single character. I was looking at their pupils and feeling they were communicating truthful emotion.

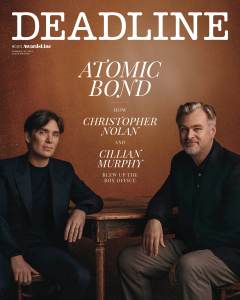

Read the digital edition of Deadline’s Oscar Preview issue here.

Animation is as powerful to convey emotions as live-action, but there are very few films where there’s true emotion in animation. Normally they’re comedy or action. There are big exceptions, of course — Hayao Miyazaki, Isao Takahata, Mamoru Hosoda, Wes Anderson — but in general, we can say that mainly they’re comedy and action and for children. I wanted to make a film for adults that has emotion, but also humor. For me, my biggest influence and reference for this film was Charlie Chaplin and the film City Lights, because there’s this dramedy. I love dramedy. I think a laugh and a tear come together. Laughing and crying, they combine perfectly. So that’s a tone that I want it to be. And for me, my perfect genre is a tragic comedy. I think it’s like life, and it reflects life. So, I wanted to make a very human-like experience. Even if they’re anthropomorphic, I wanted the audience to really connect with them.

As you said, you connected with many of the main characters, and for me there are four: Robot, Dog, Duck and Rascal. This film talks about relationships, and in relationships sometimes we have behaved like Dog, or Robot, or sometimes we’ve been Duck. Duck for me is just the perfect ideal. He’s funny and charming, but at the end he just disappeared from the life of Dog. Rascal is just a more mature love or relationship. We wanted to have some different types so that you could relate to any of those characters.