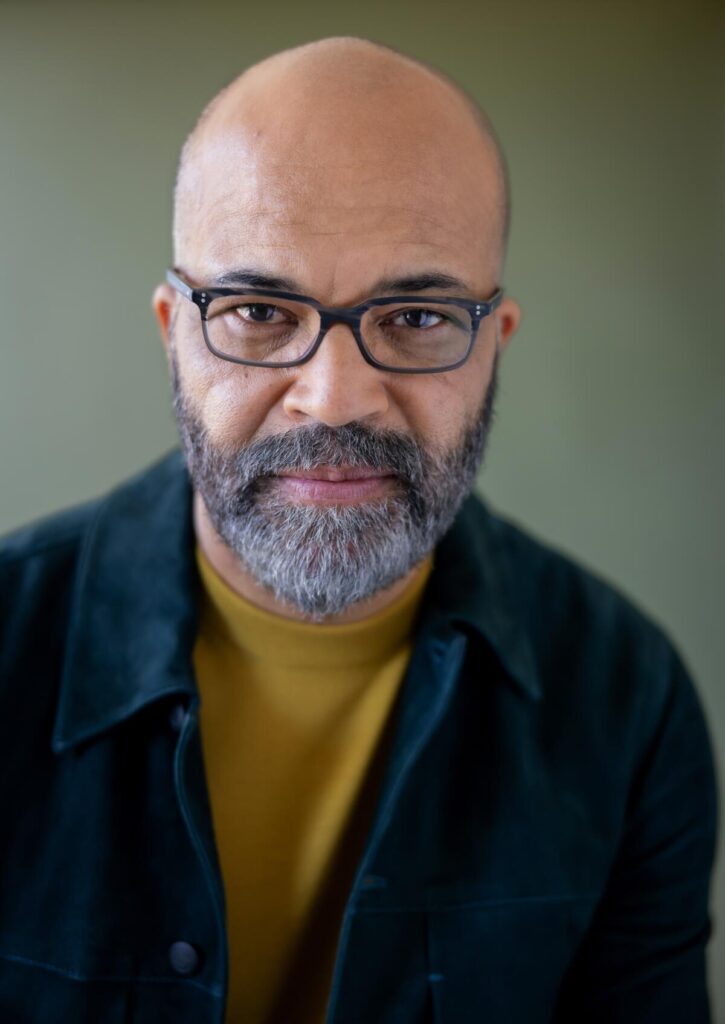

“I’d never had a meeting like that before in my career for any film that I’ve been a part of, and certainly not one that I was the lead in,” Jeffrey Wright says of a post-actors’ strike meeting that was filled with people planning out his promotional schedule for “American Fiction.”

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

Jeffrey Wright finished shooting “American Fiction” two Septembers ago and immediately, happily transitioned to becoming what he calls his daughter Juno’s “executive assistant,” helping her navigate her way through college applications and all the other stresses of a high school senior year. When she went off to school in the fall, Wright thought he’d feel liberated, that he’d enjoy, as he puts it, “a new phase of freedom.”

“But I realized that I’ve been doing the father thing for 22 years now, and I think I’m finally good at it,” Wright says, punctuating the thought with a laugh. (He also has a son, Elijah, with ex-wife Carmen Ejogo.) “Being a father has kind of been the primary thing I’ve been … and now I miss it.” He pauses, as he does often in conversation. Wright is a man who considers every word. “Yeah … I wonder what’s next.”

We’d just met 15 minutes ago. Being a father is how you see yourself, I ask. More than an actor?

“Oh, f— yeah,” Wright responds without hesitation.

“So, in a way, my life seems purposeless now,” Wright continues. “It certainly seems empty in multiple ways.”

This sounds serious. And it is, though two things should also be noted up front. First, pretty much everything Wright says in his deliberate, resonant voice echoes with meaning, with contemplation, with weight. He could read the Taco Bell menu — chalupa su-preme — and convince you that it’s a lyrical wonder.

Second: Wright’s doing OK. Really. He’s just a man given to introspection.

In the fall, Wright had time, too much time, really, to reflect. The actors’ strike prevented him from taking a job or going to the Toronto International Film Festival, where “American Fiction” premiered and won the event’s audience award. Wright would have loved to be there and talk about playing Thelonious “Monk” Ellison, an author and professor, who, frustrated with his career, drunkenly cranks out “My Pafology,” a pandering book that fully embraces cliches about the urban Black experience. Improbably or maybe naturally — the film lets you decide — it becomes a bestseller. Monk, an artist, doesn’t know how to feel about its success. After all, he wrote it in a fit of pique.

Jeffrey Wright, left, as Thelonious “Monk” Ellison and Sterling K. Brown as his less responsible brother Cliff Ellison in “American Fiction.”

(Orion Pictures)

So, yes, much to discuss — only Wright couldn’t say a word. So instead he headed west from his Brooklyn home to a Malibu rental just down the coast from fried seafood destination Neptune’s Net, where he keeps his surfboards, truck and bicycle. Time to work on himself. Mind. Body. Spirit. Find some decent waves. Power through eight-mile bike rides through the hills. (“I’ve got a little e-assist,” he says of his electric ride. “I try to use it in moderation … but it is uphill.”) Regular workouts at a wellness center, doing Pilates, acupuncture and weight training.

“I was trying to get back to the old ways a little bit, to the extent that that’s possible in these older times,” Wright, says. He recently turned 58. He knows he’s not going to get back to the shape he was in when he played lacrosse in high school and college. He couldn’t, even with all the training in the world. That’s because when he was 24, Wright was playing Puck in a touring production of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” and at the end of the first act, he leaped offstage and tore his ACL.

“The loudest silent scream in the history of theater,” Wright says.

Did you return to stage?

“Limping,” Wright says. “But, yeah, there was a second act to do.”

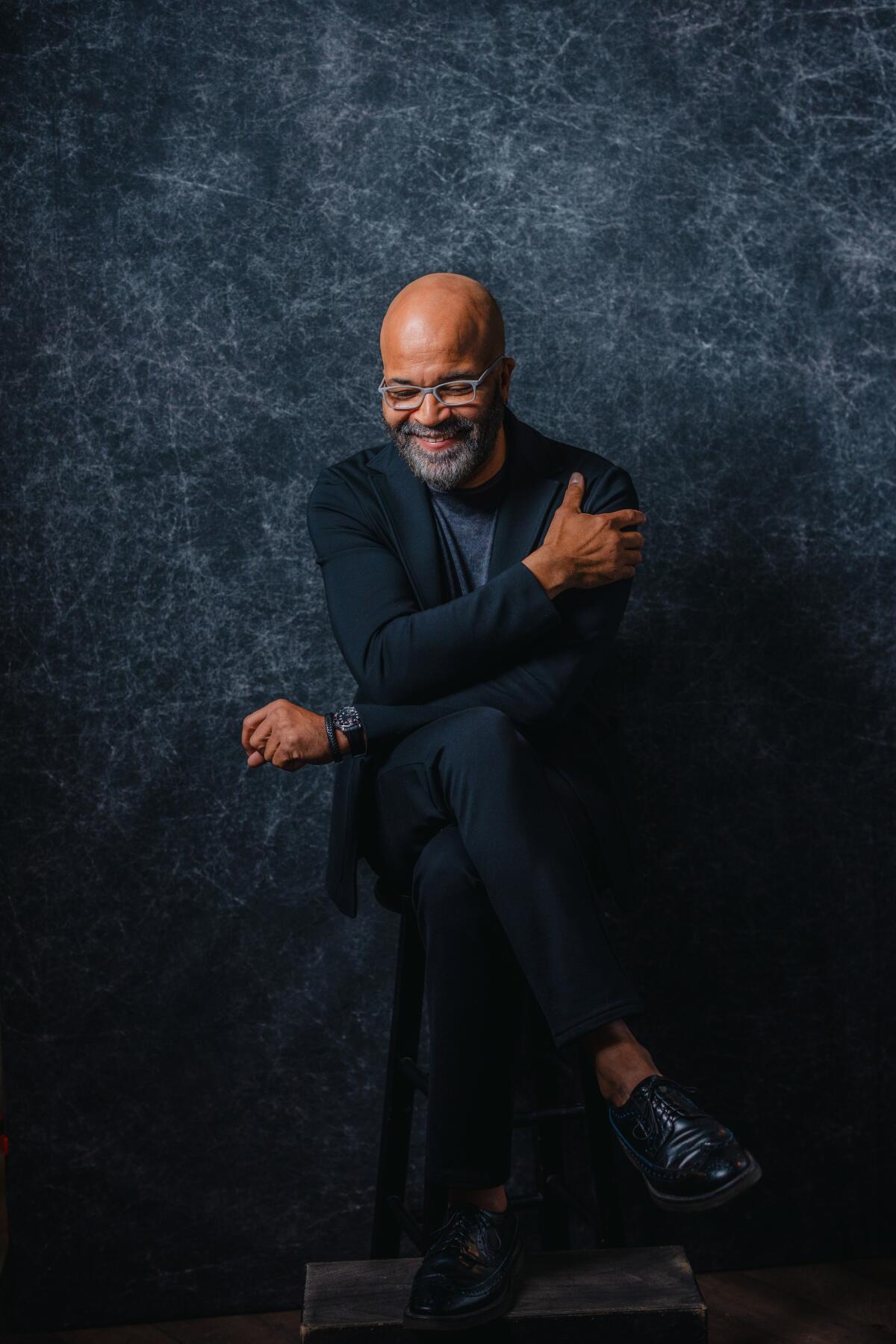

Being “young and foolish,” he never got the knee fixed until eight years later when it locked up on a backswing playing golf. It’s still not great, but being out in the ocean helps. Wright started surfing about a dozen years ago and became passionate about the sport when he moved to Los Angeles after getting cast on the HBO series “Westworld” in 2015. For the show’s first two seasons, he lived in Santa Clarita. Then he moved downtown. Then to Marina del Rey. Finally he got this seasonal rental, just south of the Ventura County line. It’s his through March.

“The single advantage of living out here is the Pacific Ocean,” Wright says. “It’s just a magnificent creature. I could never leave it.”

The morning after the actors’ strike ended in November, Wright opened his email and found a message from one of the “American Fiction” producers. You want to come in for a meeting? When? Tomorrow morning, 10 a.m. at MGM. When Wright showed up, he was taken aback. There were two dozen people in the room brimming with energy and ideas, spitballing how to support the film. One person handed him a tentative promotional schedule. It ran through March.

“I’d never had a meeting like that before in my career for any film that I’ve been a part of, and certainly not one that I was the lead in,” Wright says.

Really? Not with the three Bond movies, the “Hunger Games” trilogy or the last “Batman” reboot? Or with “Westworld” or the two movies he made with Wes Anderson?

“Nope,” he answers. “Never.”

“The single advantage of living out here is the Pacific Ocean,” Jeffrey Wright says. “It’s just a magnificent creature. I could never leave it.”

(Jason Armond/Los Angeles Times)

When Wright earned his first Oscar nomination a couple of weeks ago, that tentative schedule they gave him became permanent, including more post-screening Q&As, more career retrospectives (“it’s like your life passing in front of your eyes”), more interviews like this lunch conversation we’re having, all of which inspire the kind of “intense self-reflection” that Wright hopes might end up being a constructive exercise somewhere down the line.

After he heard he was nominated, the first person Wright called was his 94-year-old aunt, the woman who helped his late mother raise him. (Wright’s father died when he was 1.) She lived with Wright for a couple of years until Wright had a house built for her near the Chesapeake Bay, where the sisters grew up.

“I called her and asked, ‘Did you hear any news this morning?’ ” Wright says, smiling. He made the call because his aunt’s eyesight isn’t so good. “She said, ‘Oh, I heard. Congratulations.’ ” Pause. “ ‘But you know, you should have been nominated a long time ago. You should have been nominated for “Basquiat.’ ” Wright laughs. “That’s the way she is.”

The aunt was the first person he called, but not the first person he talked to that morning.

“I was in my lounge/office area in Brooklyn. I actually grabbed some dumbbells that my son had in there for whatever reason,” Wright remembers, pantomiming doing bicep curls at a furious pace. “And I glanced at my phone and a message pops up. ‘Congratulations.’ And then I looked up and saw the picture of my mom on the bookshelf.” He smiles. “We had an exchange.”

Wright’s mother, Barbara Whiting-Wright, had come up several times during our conversation. An attorney, she was the first Black woman to serve as customs law specialist for the U.S. Customs Service, where she began her legal career in 1964. She also had season tickets to Washington’s professional football team and a record collection that included Miles Davis’ “Live-Evil.” She died four years ago from colon cancer.

“As far as my life goes, she was a visionary,” Wright says. “My mom basically lined up a series of doors around me from a very early age. And they all led to someplace good.”

“Pretty tough too,” Wright adds, making sure he painted a full picture. “She had expectations.”

Did you feel like you met them?

“When I described to a very good friend of mine how I had taken care of my mom at the end of her time, he said, ‘Her investment paid off,’ ” Wright says. “He knew my mom pretty well. I think what I had described to him, what was reasonably comforting to me, was that she trusted me. And that was cool.”

Wright looks down. Our table has been cleared. We’re well past the time we said we’d talk, and he’s had adequate introspection for the day.

“All right, enough of this,” he says, rising, extending his hand. Time to head home.

Too late to surf? Probably. But Wright already has one session circled on his calendar.

“I’ll be out in the Pacific on the morning of the Oscars,” he tells me. “It calms the system.”