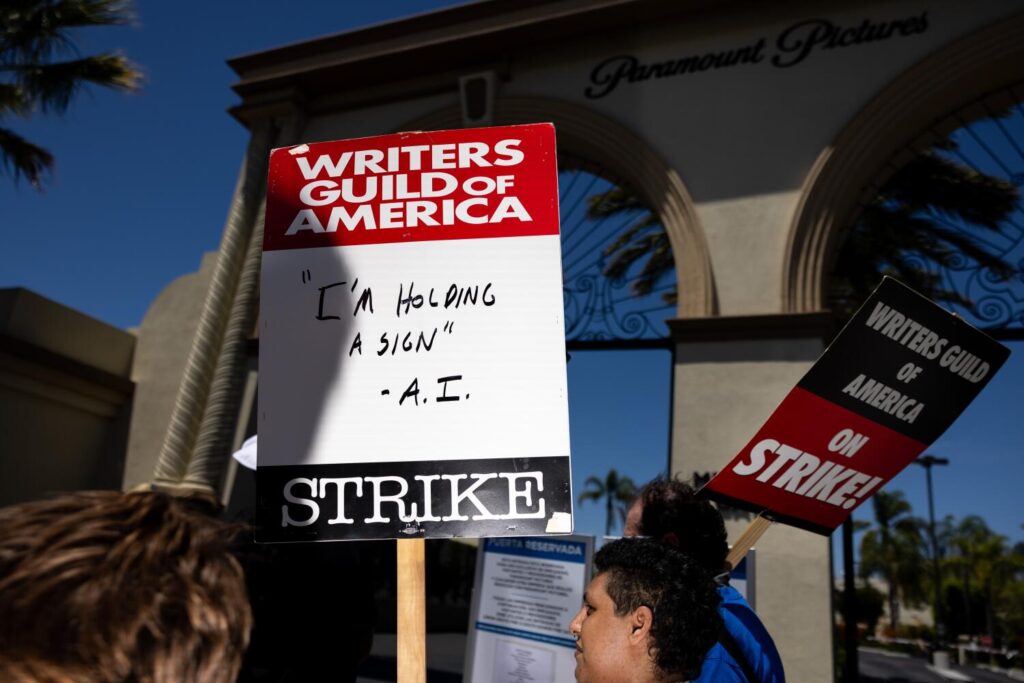

After nearly five months on strike, the Writers Guild of America has finally reached a tentative deal with Hollywood’s major studios. Among the key points? Limits on the use of artificial intelligence.

The nascent technology proved a sticking point between the two sides. In fact, AI was the last topic on which they came to an agreement, according to people familiar with the matter who weren’t authorized to comment publicly and requested anonymity. Now, the proposed contract aims to establish guardrails around its use.

According to a summary document from the WGA, the contract — which still needs to be ratified by the union’s members — would let writers choose to use AI when performing writing services, with the studio’s permission. But scribes couldn’t be made to do so. Companies also wouldn’t be able to give writers AI-generated material without telling them.

But screenwriters aren’t the only ones worried about what automation means for film and television. The Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists remains on strike and has voiced concerns of its own about artificial intelligence. “We are all going to be in jeopardy of being replaced by machines,” SAG-AFTRA President Fran Drescher said in July.

It’s already become a hot-button issue. SAG-AFTRA hoped its negotiations with the studios would secure regulations around how AI could be used in filmmaking as well as the use of past performances to train AI models.

In turn, the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers — which represents the studios in their negotiations with both SAG-AFTRA and the WGA — proposed what it framed as groundbreaking new rules that would’ve required that performers consent to the creation and use of their AI-generated digital replicas.

Negotiators from the union were unsatisfied, worrying that background actors could still be scanned once and then see their likenesses reused indefinitely. The AMPTP maintained that actors would retain control. Nevertheless, it’s been clear through the strike that the studios see this technology as a potential time and money saver.

Once talks resume between SAG-AFTRA and the studios, the AI debate could prove even stickier for them than it was with the writers.

Some see the threat of displacement posed by the technology as more imminent for actors than it is for writers, which could incentivize SAG-AFTRA to pursue a longer, more aggressive strike in a bid to proactively regulate a technology that grows more powerful every year.

Movies already feature AI-enabled performances, after all, including scenes in which dialogue was tweaked during post-production and ones in which a digital “clone” de-ages an actor or brings them back from the dead. Companies in the frothy AI market also have pitched the technology as a means of disrupting motion capture and stunt work, and one background actor told The Times this summer that she’s had her body scanned twice in order to be digitally inserted into crowd scenes.

That’s in contrast to the world of writing, where — to the extent that ChatGPT and other text-generating machines can churn out believable prose — it’s still widely believed that it won’t be cutting humans out of the loop anytime soon.

Actors also have less protection than writers when it comes to aspects of intellectual property law, said David Gunkel, a professor of media studies at Northern Illinois University and the author of “The Machine Question: Critical Perspectives on AI, Robots and Ethics.”

“Written content … falls very readily under existing copyright stipulations,” Gunkel said. (Indeed, several authors are currently suing software developer OpenAI, accusing it of violating their copyrights.) “With regards to an actor’s image and how it is manipulated in the future by the holder of the copyright to a particular motion picture, that’s a little bit of a different kind of negotiation, because the actor doesn’t hold the copyright to his or her image. It’s the studio that owns the image.”

In the absence of firmer legal protections, he added, actors may have to rely more heavily on getting a strong union contract.

Regardless, studios are continuing to hire in the sector. A recent Times survey of job openings at major media and entertainment firms found widespread demand for AI experts.

There’s also reason to think that the end of the writers’ strike would mean a faster end to that of the actors.

Scott Keniley, an entertainment lawyer with the artificial intelligence and virtual reality music company Soundscape, said that the WGA deal could increase the pressure on SAG-AFTRA to return to work.

“They lose some of their leverage,” Keniley said, “because the writers have already got what they wanted.”

The AI regulations that the WGA and studios settled on could also offer SAG-AFTRA a template for structuring a deal that projects job security but still capitalizes on the useful aspects of AI.

And the WGA contract could prove instructive for other industries too.

Nearly half of Americans are concerned about how AI will affect their jobs, per a recent Times poll, and the WGA strike is an early case study of a trend that will almost certainly continue: employee pushback on efforts to automate their livelihoods.

SAG-AFTRA officials declined to comment on whether the WGA contract will offer them a playbook for bargaining their own AI policy. The AMPTP did not respond to a request for comment about how the pending AI agreement with the WGA will inform their negotiations with SAG.

“AI will continue to play a role — and will continue to be a pressure point — in the development of new content,” said Gunkel, the media studies professor. “This is just the first step in a rather long process of … trying to figure out what is the place of these technologies in the creative industries.”