This story contains spoilers from the documentary “The Deepest Breath.”

In 2017, Laura McGann read a story in the Irish Times about a fatal accident involving Alessia Zecchini, a preternaturally gifted freediver from Italy, and Stephen Keenan, a well regarded safety diver, at the Blue Hole near Dahab, Egypt — a notoriously dangerous submarine sinkhole nicknamed the “divers’ cemetery.”

Even though the Irish filmmaker didn’t know a thing about freediving — “At one point I googled ‘What is freediving,’” she said — she was immediately intrigued by the “incredible images of people behaving more like seals or dolphins, just holding their breath underwater, swimming endlessly.” She couldn’t resist trying it herself, but quickly discovered her lung capacity was less impressive. “I’d try to hold my breath and then I’d gasp.”

What started as a trip down the YouTube rabbit hole became a six-year filmmaking journey resulting in “The Deepest Breath,” a gripping documentary, now streaming on Netflix, that tells a tale of underwater tragedy and arrives as the implosion of the Titan submersible remains fresh in the public memory.

Using a trove of archival video, photos and audio recordings, “The Deepest Breath” follows Keenan and Zecchini on separate journeys to the top of the freediving world. In the sport, athletes descend hundreds of feet below the surface of the ocean using a single breath, no oxygen tanks and little equipment other than a rope.

Zecchini fell in love with the sport as a precocious child who was barred from competing until she turned 18 — much to her dismay — and was a formidable international contender by her early 20s. After traveling the world, Keenan, originally from Dublin, found his calling as a highly trusted safety diver accompanying athletes on their ascent and intervening if they blacked out or otherwise needed assistance.

Their paths crossed at a competition in 2017 where Zecchini, with guidance from Keenan, set a world diving record of -104 meters. An intense connection was immediately apparent. They started training together, became romantically involved and set their sights on an ambitious new goal: In July 2017, Zecchini was attempting to freedive to an arch 180 feet underwater at the Blue Hole, then swim through it — an extremely dangerous feat only one woman, the legendary Natalia Molchanova, had previously accomplished — when disaster struck.

“Their connection with the sea and what led them together — that story I found compelling in a really deep way,” McGann said.

While it’s likely to induce panic attacks in anyone with thalassophobia, “The Deepest Breath” is also a stunning work of filmmaking that includes hypnotic shots of divers descending into the darkness and visceral, on-the-scene footage from diving competitions — like an underwater “Free Solo.”

Speaking by phone from Ireland, McGann told The Times about the “magical” process of making the documentary. (If you haven’t watched it yet, you should probably stop reading now. And avoid Google while you’re at it.)

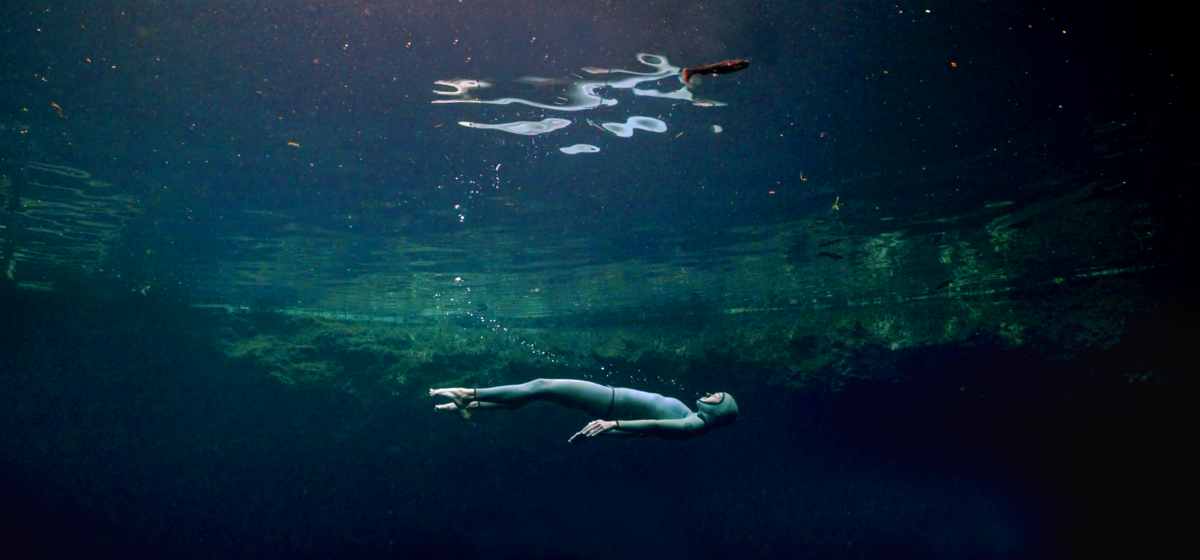

An image from “The Deepest Breath.”

(Netflix)

How did you get Stephen and Alessia’s friends and family involved in the documentary? Was there any reluctance on their part ?

It was a very slow process. I was intensely aware that the family and Alessia had just been through a massive tragedy and would be grieving for a long time afterwards. This photographer Daan Verhoeven posted this beautiful photo essay all about Stephen [online]. I reached out to him initially, because he had put something out there. He then put me in touch with another friend and it was really straight into the freediving world [from there]. Mainly it was the safeties [safety divers] and the photographers that brought me in and explained to me what it was all about, how it works, what happens to the body when you go down.

I thought I wouldn’t talk to Stephen’s family for a long time. But it’s such a small community that Peter, Stephen’s dad, actually ended up getting in touch with me, and would you believe he lived across the road from me in Dún Laoghaire [a suburb of Dublin]. I swear to God. I’d been chatting to people from all over the world for the best part of six months and then Peter says, “Let’s meet for coffee in Harry’s Bar in Dún Laoghaire.” If you go downstairs from my apartment, it’s Harry’s Bar. I just couldn’t believe it.

We chatted for about an hour and immediately he was on board. Then the rest of the community and Alessia came on board because Peter had given us his blessing. Stephen had saved an awful lot of people’s lives [as a safety diver]. There were a lot of people who wanted to come forward and talk about how he had helped them.

How did you gather all the archival video and audio recordings in the film?

It’s hard to make a documentary about somebody when they’re not there to tell you [their story] themselves. When I met Peter for coffee, at the end of our conversation, he put a little pen drive on the table, said, “Look, there’s some interviews with Stephen on that.” Peter had asked [a friend] Mícheál Holmes, he said, to record some interviews with him. Mícheál was a radio producer. He ended up doing about 12 interviews with Stephen, and there’s about 14 hours of audio.

I went home that day and started to listen to the audio. It was enchanting. He traveled in Australia, North America and South America, Asia, and then all over Africa. It was like in “The Princess Bride,” when the little boy’s in bed and the granddad is telling him all the stories and he’s hooked. Stephen just transported me to the middle of the Congo or to a beach in Brazil or the top of volcano. The detail that he gave — he just remembered everything. He absolutely had me hooked. That’s when I realized that because we have this record, we could make a film. Peter also had 24 DV tapes from when Stephen was traveling. He gave me those too.

After that it was trying to interview everybody and seeing what [footage] was available. Did anybody film Alessia when she breaks the world record in [the] Vertical Blue [competition] or Stephen saving Alexey [Molchanov, a world champion diver and son of Natalia Molchanova]? Was anybody even there that day with the camera? And time and time again, we were absolutely flabbergasted by the generosity of the freediving community with their footage and the fact that they had filmed absolutely everything.

Stephen Keenan and Alessia Zecchini in “The Deepest Breath”

(Netflix )

A note at the beginning of the film says you used footage from the actual events, along with “additional archive material and reconstruction” in some scenes. What was your approached to re-creations?

We’d researched for a year before we shot any of the interviews, so we really knew the story we were going to tell. It was just about trying to find the archive. Across the globe, people were going into their wardrobes and getting archive that was, like, 20 years old. Once there was no stone left unturned, we identified the gaps [in the footage]. There were never any full scenes that weren’t covered at the time [they happened]. It was only a shot here or there. So not only did we have this incredible wealth of archive, we got to go and make a film underwater. So we filmed in Dahab, Egypt, in the Blue Hole with Alessia, in the Bahamas at the Vertical Blue competition and in a cenote in Mexico.

How did that filmmaking process work?

A lot of the time we filmed with a freediving cinematographer named Julie Gautier. I was on the surface of the water, holding on to a noodle. We’d have Julie with her camera and a number of safety divers — five or six — and the freedivers. And they’d go down, get the shot at about 30 meters. Come back up, show me the shot on the surface. And I’d say, “That’s great, guys. Can you just do that one more time?” And they’d say, “Yep, no problem.” They’d fly back down again. It was actually completely magical. I didn’t know you could make a film like this. It was like having a fleet of dolphins who were like, “OK, I’ll get that shot.” Really what it taught me was that humans are capable of a lot more than I realized in the water.

Freediving cinematographer — that is a very specialized job.

I felt so unskilled next to them. They’re shooting this beautiful footage while holding their breath. I was holding on to a noodle on the surface.

So you re-created some of the accident in Dahab with Alessia?

We didn’t re-create the accident. We went out to the Blue Hole and Alessia just dove down a little bit. Because the arch is so deep, it’s not something that freedivers try to do anymore. In order to get some shots of her under what looked like the arch, we went to the cenote in Mexico. It’s much shallower — just two meters. Obviously, safety was our number one thing. We certainly weren’t going to take any risks.

Newsletter

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Still, that must have been intense for Alessia to be back there, reliving that moment.

Alessia has held Stephen in her heart in a really unique way. She has leaned in to everything that he said to her during their time together about diving, about her ability, about believing in herself. Alessia dives in the sea and feels connected to Stephen when she does.

At the beginning of the film, there’s a stunning sequence of Alessia diving during a competition, descending deep underwater, then resurfacing under dramatic circumstances. It goes on for three minutes with only a few quick cuts. Can you tell me why you opened the documentary this way?

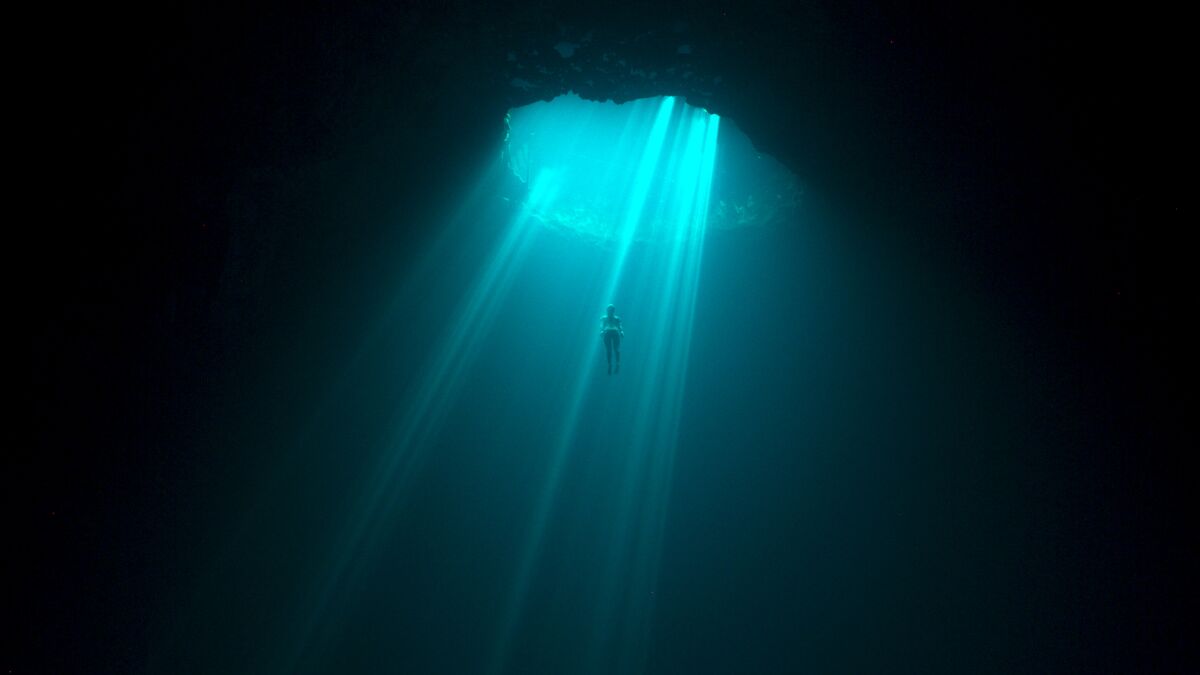

There was no point in starting the story anywhere unless the audience understands what freediving is and what the stakes are. And the only way to understand what freediving is without going freediving yourself is to be with a diver and watch them and spend the time with them — the crucial piece is the time — as they descend, and you know they’re holding their breath the whole journey. And it’s getting darker and darker than you ever imagined it possibly could. And they go for longer than you ever imagined that a person possibly could. And then they have to turn around and come back up. You’re under no doubt as to what is going on here.

How do they film that?

It’s an underwater drone on a rope and it senses the movement and follows her. It’s called the Dive Eye. A lot of the other stuff is shot by scuba divers or freedivers. That’s the only piece that’s shot by [the drone].

“The Deepest Breath” on Netflix

(Netflix)

How did you decide to structure the narrative the way you did — following Stephen and Alessia’s journeys in tandem and only revealing at the end, when we see Alessia in an interview for the first time, that she survived the accident and he did not?

It goes back to the start when I met Peter for coffee in Harry’s Bar and he passed me the pen drive. That was the piece that we [thought we] would never be able to get — Stephen telling his own story. I thought, this is an opportunity to tell the story in the moment, to not be looking back having other people tell you about this man who had an accident. You’re actually with him on his journey. I thought that was key to elevating this into something much more cinematic and immersive. I’m telling Alessia’s story as well, so we have to also treat Alessia in the same way, using [archival] video, because if you have Alessia there and not Stephen, you already know something that they didn’t know in that moment.

Did you ever go freediving yourself?

I was at Vertical Blue in the Bahamas. The competition had just ended and they were about to pull up the rope and they said, “Does anyone want to give it a go before I pull it up?” And they said, “Go on, Laura.” There was a whole load of divers around me. I pulled the rope down to three meters, and I pulled the rope back up again. And that’s my personal best.

Over the course of making this film, did you get a sense of why freediving is so appealing, despite the inherent risks?

They know the risks and they do everything in their power to mitigate them. They take it really seriously. But there’s a number of pieces that I think make it appealing.

Alessia talks about when she’s going down into the dark, that it’s the last quiet place on Earth. You’re alone with yourself. Natalia Molchanova said it’s not just a sport, it’s a way to understand who you are. There’s a spiritual side to it; it’s like deep meditation. You do meet yourself down there.

There’s also something quite physical, which is the freefall that happens around 30 meters. When you’re diving, you’ve got to kick down quite hard initially, but [once you reach] 30 meters, it switches and the pressure above your head pushes you down. You can completely relax your arms and legs, and you will just fly down through the water. If you know what you’re doing, it can be like flying underwater, or like being in space. That, to me, sounds pretty amazing.