On the Shelf

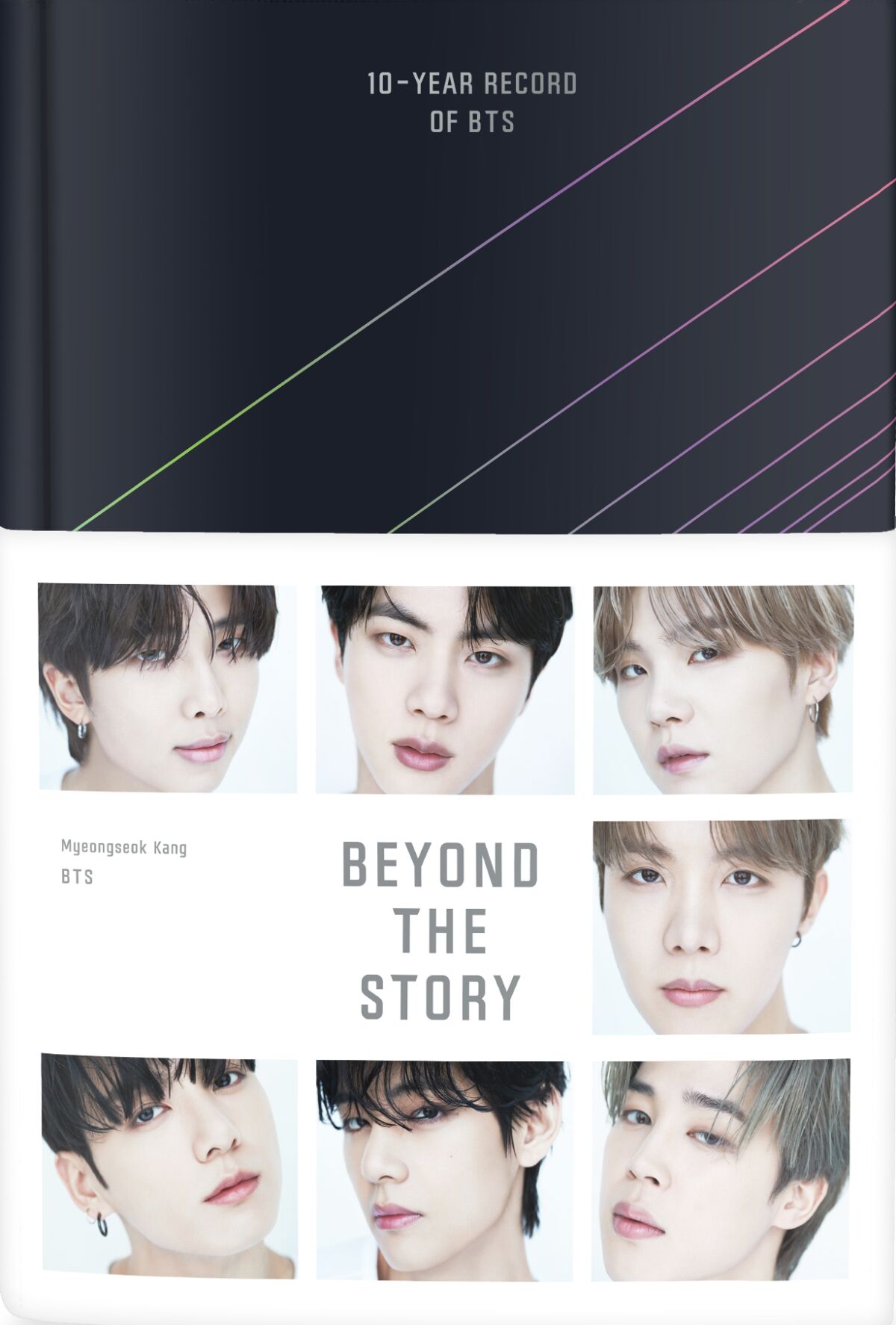

Beyond the Story: 10-Year Record of BTS

By Myeongseok Kang

Translated by Anton Hur, Slin Jung and Clare Richards

Flatiron: 544 pages, $45

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The K-pop juggernaut known as BTS has dominated the American music scene in an unprecedented way. The group’s seven members — RM, Jin, SUGA, j-hope, Jimin, V and Jungkook — have performed at the Grammys and the American Music Awards, and most of their music videos have over 1 billion views on YouTube.

The band released “My Universe” with Coldplay, whose frontman, Chris Martin, seemed to speak for billions when he said, “It’s very special to me that the most popular artist in the world speaks Korean … and it just feels very hopeful to me, in terms of thinking of the world as one family.”

“Beyond the Story: 10-Year Record of BTS” is the first biography of the group, published in time for their 10-year anniversary. Written over three years, the book weaves in an oral history with group interviews by the biography’s author, Myeongseok Kang. Fans might be surprised at the shaggy underdog tale contained therein. Here are some major takeaways.

BTS was born in a K-pop dormitory

In the aughts, Korean idol groups were having their big moment, and not just domestically. The U.S. went wild over rapper Psy’s “Gangnam Style” in 2012, proving that K-pop could find a place in the Western market. During this time, Korean teens swarmed to dance hagwons (private academies) where they could study dance, and make important connections in Seoul’s entertainment industry.

That industry revolves around “idols” — K-pop celebrities who perform in solo acts or groups. Large entertainment companies scout Korean teens to become idols or hold packed auditions to anoint idol “trainees,” whom they then mold into pop stars. SUGA and j-hope entered the idol audition process before joining Big Hit Entertainment as trainees; j-hope had been auditioning for other companies before his dance hagwon recommended him for Big Hit.

The trainees sign contracts and must live in a dormitory, where they eat, sleep and breathe K-pop until their debut. Jin describes the dorms as having “clothes strewn everywhere, cereal scattered on the floor” and plenty of dirty dishes, explaining that they worked 14-hours days and were simply too busy to live tidy lives.

While many of the BTS members wondered how they made it to their debut without quitting, Jin said adjusting to life in the dorm prepared him for the surreal state of being an “idol” in the K-pop world.

Breaking into the industry, BTS was not welcomed with open arms

Because the K-pop competition was so fierce, the odds of success as a group were incredibly slim. BTS members struggled at first with impostor syndrome, performance flubs and bullying from the public. Even before they made their debut on a televised showcase, naysayers were already dragging the group in the comments sections of online forums. Their first gig brought in only about a dozen fans.

It was a long slog from there. Jimin said the group would avoid making eye contact with other groups in green rooms. For the first time they were forced to compare themselves vocally with other K-pop idols.

“If I wanted to improve somehow, I had to practice my singing, but I didn’t know how to practice,” he said. “So I just kept singing blindly. Every time I made a mistake, I went to the bathroom to cry.”

Despite winning best new artist awards at many major Korean music awards shows in 2013, the group was shunned by peers and more established artists. According to the biography, no one in the industry would speak to them, they couldn’t approach anyone, and their nights consisted of little more than quick thank-you speeches at contest podiums before being shuttled back to the dorms.

Several times throughout the biography, Kang references various public insults aimed at BTS — but opts out of repeating the jibes.

In comparison to the “big three” Korean entertainment companies that debuted many of the era’s K-pop stars, Big Hit Entertainment might be considered more of a startup. It didn’t have the deep pockets to market BTS at the level of bigger players, so the group built a following instead through vlogging.

YouTube videos featured members dancing, rapping, spending Christmas together; individual vlogs were made in the style of confessional interviews; Jin launched his own “Eat Jin” vlog in which he filmed himself eating.

Kang writes that the vlog approach to self-promotion was “a complete rejection of genre norms in Korea’s idol industry, where every frame of every video was perfectly produced for public consumption.” And yet it was exactly this sense of spontaneity and intimacy that fueled BTS’ fanatical fan base.

BTS had to address complaints their lyrics were misogynistic

It wasn’t all adoration from there on out: The band came under fire for two songs that fans said perpetuated gender inequality and misogyny. The 2014 song “War of Hormones” featured lyrics that translate to “Girls are like an equation / us guys just do them (yup) / Imma give it to you girl right now / A woman is the best present.” And the 2015 song “Joke” includes lyrics that translate to “”You’re the best woman, the best vagina …. But now that I think about it, you were never the best / I will stop calling you best and instead call you gonorrhea.”

In July 2016, Big Hit and BTS issued a statement responding to the complaints, saying, “We learned that music creation is not free from societal prejudice and fallacies,” and “Furthermore, we became aware that it may also not be desirable to define the value of women and their role in society from a male perspective.”

RM, who wrote the lyrics, told Kang that this early reckoning helped him recognize the problem in time to change his attitude and behavior.

According to Kang, gender sensitivity training is now obligatory for all all artists at Big Hit (now known as HYBE) before they can debut.

The band still felt like outliers before winning AMA’s artist of the year in 2021

BTS had conflicting emotions when it came to awards shows. They struggled with industry peers in their early days, and felt they weren’t welcomed or respected as artists. But in 2021 they wound up on American soil just as a lull in the pandemic opened a window for a public appearance at the American Music Awards. They also happened to be up up for several major awards, including the most coveted: artist of the year.

SUGA recalled that their American television debut, in 2017, had been on the same stage for the same awards show (at the Microsoft Theater in Los Angeles). When the group won artist of the year, he couldn’t help thinking someone had made a mistake — or the world was playing a prank on him.

“I felt like we’d been outsiders or outliers until then,” RM said. “But now it felt, not like we were in the mainstream necessarily, but we were being welcomed more.”

Jung Kook said winning the award felt like the beginning of a new chapter: “Who would’ve thought we could win artist of the year at an American awards ceremony? It was so shocking. It sent chills down my spine.”

BTS fans know the feeling.