The Flash may not have rebooted the DC multiverse, but it has one thing going for it. Of all the multiverse movies out there — the Spider-Verse, Everything Everywhere All at Once, Avengers: Endgame, Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness — there’s only one that’s using the best version of the multiverse ever invented by comics.

And that’s no faint praise. The idea of superheroes has been intertwined with parallel earths for over 60 years. That’s 60 years of innumerable writers, editors, and artists exploring every narrative nook and cranny of that combination, with a correspondingly huge number of contradicting explanations of how it all works.

Can you or can you not time-travel to change the past? What’s the difference between a parallel universe and an alternate timeline? What the hell even is a “pocket dimension”? When comics sit down and try to hash out the rules, it’s almost always prescriptive. But The Flash’s version of the multiverse, ripped from the pages of some of the nerdiest comics ever made, is descriptive.

Instead of mandating how a superhero multiverse should work in an ideal setting, it takes a realistic look at how superhero multiverses actually work in practice, and fits itself around that.

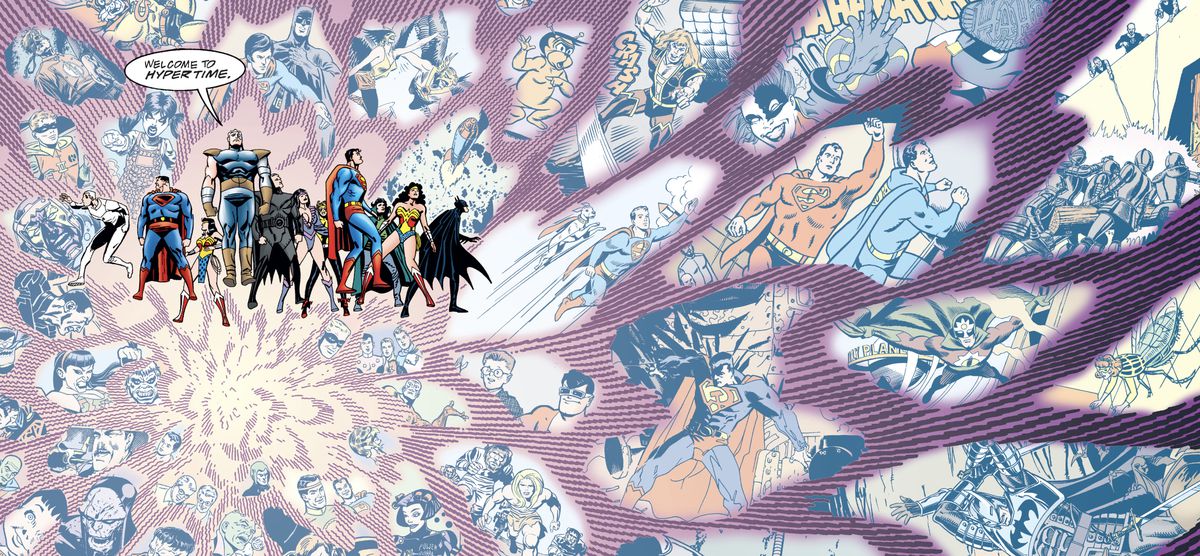

And it’s called Hypertime.

Wait, don’t leave, I promise Hypertime is cool

If you’ve read this far, you probably have an idea of how the Superhero Multiverse works. A multiverse is a collection of universes, all at least slightly different, and never interacting with each other. (Except for how the protagonists of stories are constantly interacting with them.)

Some worlds are different because of something that happened in their past (see: Loki on Disney Plus). Some worlds are just different for no particular reason (see: Spider-Verse). But forget about teasing out the difference between “parallel earth” and “alternate timeline” — in superhero cosmology, they’re essentially interchangeable. The “what if?” question itself includes the concept of linear time, and changes to the past having an effect on the present. “What if this one thing was different? What would have happened next?”

[Ed. note: The rest of this piece contains some minor spoilers for The Flash.]

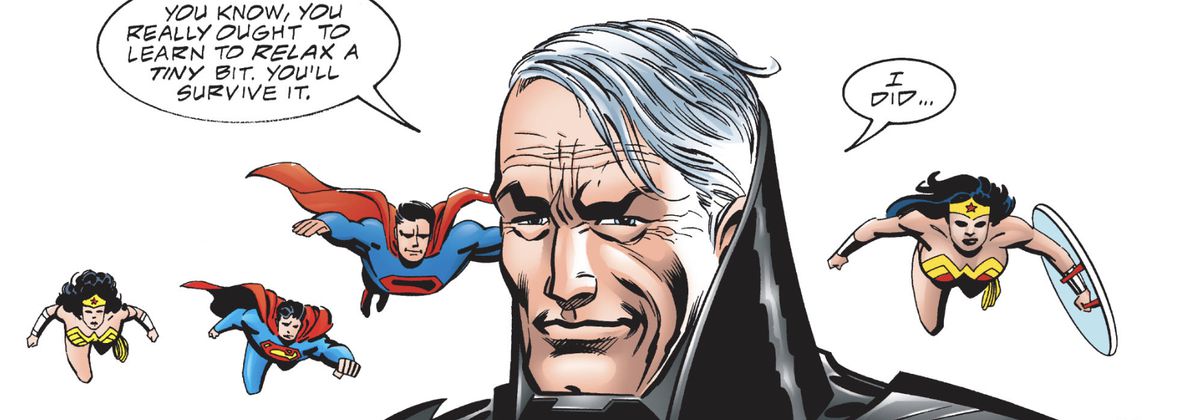

But in The Flash, the notion of cause and effect gets thrown right out the window when Michael Keaton’s Bruce Wayne throws a bunch of cooked spaghetti on a table. He does this to explain how a relatively isolated change — The Flash’s mother was never murdered — could have created a timeline in which Batman was a completely different person.

Timelines split off in moments where things could have gone one way or another, Bruce says. But, like floppy strings of spaghetti, they can bend back toward each other, too. By changing the past, The Flash knocked his timeline around until it touched a bunch of different spaghetti strands. Strands where Superman never made it to Earth, and Eric Stoltz played Marty McFly.

And that’s Hypertime, baby!

What is Hypertime?

Hypertime is a concept credited to comics creators Mark Waid and Grant Morrison that seeks to provide an explanation for the many contradictory versions of the story of the DC Universe.

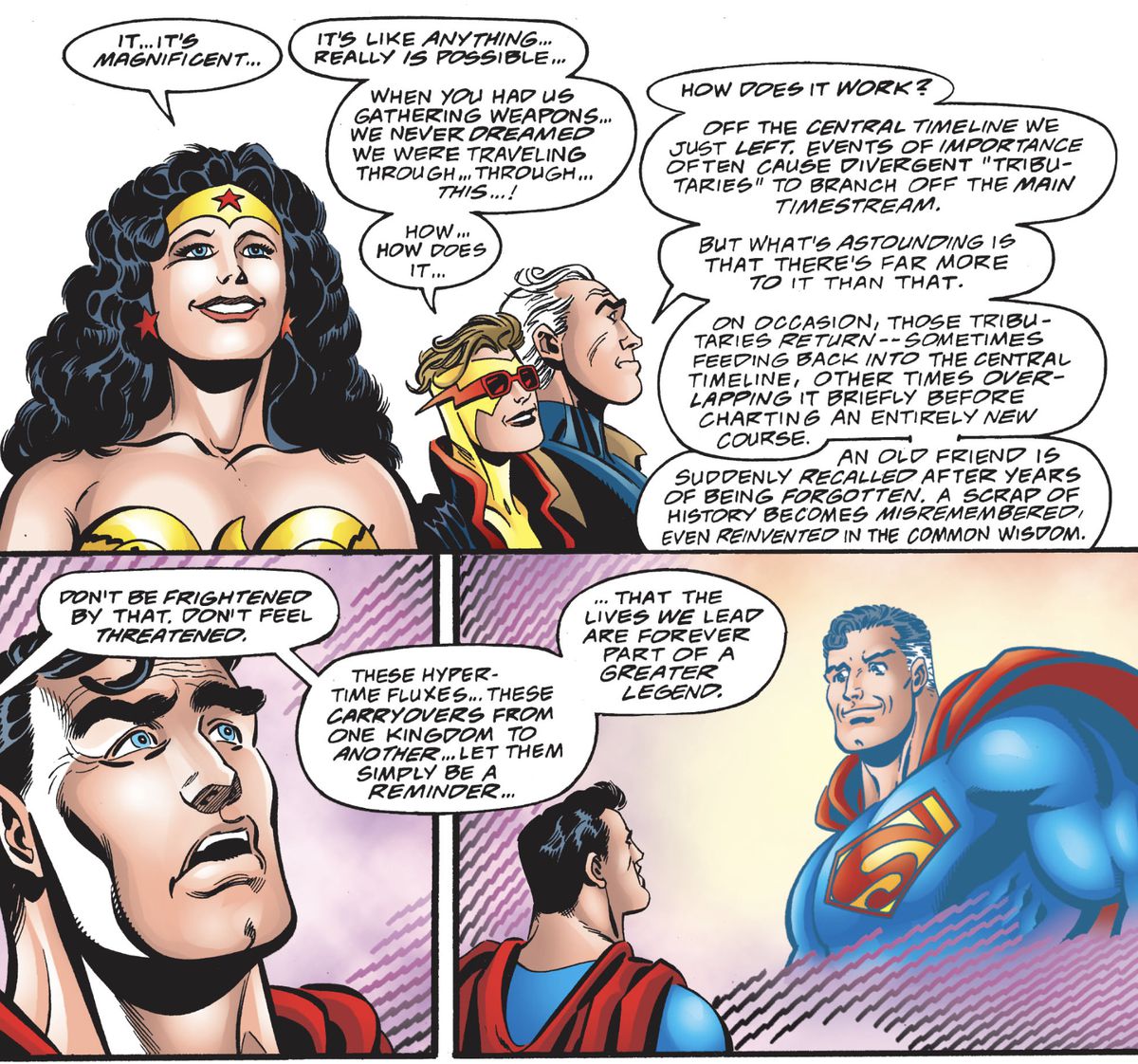

Classically, fictionalized time travel likes to imagine time as an endlessly branching tree, with a branch for each way that events could have happened differently. But Hypertime supposes that time is like an endlessly forking river. And the thing about rivers is that they can flow back into themselves.

A fork of a Hypertime river could contain one river where the minor supervillain Catman met his untimely end in the belly of a hyper-intelligent gorilla, and one river where the whole gorilla thing was actually a metaphor/bad dream. The former river is a thing that really happened in DC Comics. And you could say that the rivers flowed back into each other when writer Gail Simone decided to use Catman in her first Secret Six miniseries anyway.

And if the death of a minor villain is a little stream, then parallel Earths with their own full histories are mighty rivers, with tributaries cleaving off and feeding back in as characters and events are remembered, forgotten, prioritized, and deprioritized. Do we really need an explanation for why Cyclops’ eye beams are setting things on fire in this story, when we all know that canonically they’re not incendiary? Can we just say we’re getting a little flow from the stream where Cyclops’ eyes shoot lasers instead of “beams of pure force”?

“But!” you cry. “If the details of the setting can change without explanation, then the reader will become confused or lose interest because events don’t seem to stick or ‘matter.’”

And I’ll look down and whisper, “No. They won’t. Because you just described the experience of reading superhero comics.”

This is the zen of long-running comics universes, which, until the extremely recent advent of digital offerings like Marvel Unlimited and a healthy market for collected editions, was a decadeslong ongoing story that was simply impossible to read up on. This is what I tell people who are worried they don’t know enough comic book continuity: Don’t worry about it.

Sometimes, Batman is a guy with five former Robins and three former Batgirls, and he almost got married to Catwoman once. Sometimes, Batman has only ever had two Robins and one Batgirl, and he almost got married to the Phantasm once. Sometimes Batman is an old man who comes out of retirement and he has one Robin, who is a girl. Sometimes Batman is an old man who mentors a teenager named Terry into being the new Batman. Sometimes Batman is a Lego dude. And I think it’s pretty clear that we’re cool with all of that!

Even if we’re just talking about the main DC Comics universe, Batman has been at least three different Batmans with three slightly different histories. And before Marvel Comics fans get in here and tell me that Marvel doesn’t do this because Marvel doesn’t have reboots, Marvel’s lack of reboots arguably makes Hypertime an even better explanation for its continuity than DC’s.

It may be technically true that the Magneto of today is the same Magneto who was once regressed back to a baby and had to grow up again. It may be technically true that the Punisher served in Vietnam. It may be technically true that a cosmic creep once impregnated Captain Marvel with himself, had her give birth to him, grew up in a single day, and then brainwashed her into falling in love with him.

But you won’t find a single Captain Marvel comic talking about that these days, because it was a terrible story that everyone desperately wants to pretend did not happen. Hypertime is the perfect version of the multiverse because it’s not describing linear continuity at all. It’s describing how superhero universes actually operate.

Deep down, underneath all the promises, comic book continuity is forged by creative people choosing to use the bits they like and ignore the bits they don’t like. The fundamental forces of cause and effect in comic book universes aren’t subatomic; they’re just creative decisions. Which is why Hypertime is particularly perfect for a superhero “universe” so loosely connected as to have almost no connections at all — like the movies in Warner Bros.’ DC Films stable.

Can Jason Momoa’s Aquaman hang out with the Batman played by Ben Affleck? What about Michael Keaton? George Clooney? Robert Pattinson? What about whoever they pick to star in Batman & Robin? If the story is good… does it really matter? That may be the most powerful thing about The Flash introducing Hypertime right before Warner Bros. takes things in a very different direction. It doesn’t matter how the studio’s new multiverse works — whether it has parallel earths, or alternate timelines, or Elseworlds.

Hypertime — and therefore, The Flash — encompasses them all.