In a high school gymnasium, three hours from Salt Lake and seven from Las Vegas, the throaty warble of a fiddle competed with the sound of cowboy boots squeaking on wood. Men triple-stepped and women followed, curling in and out of their embrace.

Dance instructor Amy Mills surveyed the room, assessing, approving, correcting. She cautioned the hundred or so people who’d signed up for her rodeo swing workshop: At the dance tonight, you’ll see ranch kids swinging at warp speed. Don’t do that. Take it slow.

Kirsten Gleissner, left, and Andrew Church dance together during a rodeo swing workshop at the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering.

(Bridget Bennett / For The Times)

Andrew Church was once one of those kids, and swing dancing, its steady rocking, and its twists and spins, comes easily to him. As a teenager, he’d drive from his family’s cattle ranch, down a sagebrush steppe dotted with juniper and pinyon and into town for a night of dancing.

The rhythms of Church’s life contrasted with those of many of his classmates who lived in that town. They had summers off. They didn’t know what it was like to step off a school bus and see a horse trailer waiting, a reminder of a long afternoon of chores that awaited him— moving water around the meadows or branding calves. They didn’t feel the isolation of the ranching life.

After he graduated from college, Church abandoned ranching. He spent his 20s on ships navigating the Pacific. Being out on the water, working with three-story engines, was a marvel. But from time to time, he’d hear a song that made him yearn for home.

Church, 33, eventually returned to his childhood haunts — including that high school gymnasium. He was one of thousands who gathered in February for the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering, a weeklong festival of Western folk music and literature staged in the upper reaches of Nevada’s Great Basin Desert.

Poet Jake Riley performs at the Western Folklife Center during the weeklong festival.

(Bridget Bennett / For The Times)

The event, which started in 1985 and paused for two years because of the pandemic, has its origins in oral storytelling where ranch hands spoke of cattle wrangling and nostalgia for simpler times. Over the years, cowboy poets found inspiration in events such as the 2008 financial crisis and environmental issues. The genre continued to grow with other poetry gatherings, anthologies and articles in academic journals.

Today, it’s an affinity for the land and all that it produces that seems to unite many of the performers and attendees, a yearning for authenticity even if it has little to do with the cowboy mythology.

::

Ranching is a sobering enterprise, frequently characterized by frustration and financial insecurity. Winters are bitter, summers are sweltering, and drought threatens acres of pasture land across the West.

Today, there are 700,000 cattle operations in the U.S. compared with more than a million 20 years ago.

The number of people working on farms and ranches is steadily declining, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. In 2021, 847,600 people worked as a farmer, rancher or agricultural manager in charge of “establishments that produce crops, livestock and dairy products,” compared with 1.2 million in 2010. That number is projected to drop by 3% over the next 10 years.

As the industry consolidates and is increasingly dominated by large corporations, families that run small operations often need outside income in order to survive. Church, who returned to the family’s ranch to help run cattle, works full time for the town’s gold mine.

Gene Veeder, a cattle rancher and musician from North Dakota who attended the festival with his daughter Jessie, said music has helped him keep his family afloat at different times, especially when Jessie was an infant. During the 1980s, he made about $200 a week from gigs — enough for groceries.

Musician Gene Veeder warms up backstage.

(Bridget Bennett / For The Times)

Jessie Veeder, 39, is a singer and guitar player and a mainstay of the Elko gathering. Her folksy ballads depict the family’s 3,000 acres at the edge of North Dakota’s badlands, songs that have been in the family for 110 years, first as a homestead and now as a small cattle ranch in Watford City.

She has fond memories of riding horses with her father across the terrain of purple buttes and lush green pasture, but even though her songs are tinged with nostalgia, she makes it clear that ranching isn’t exactly a bucolic life. “Like 20%, or maybe 10%, is the cowboy stuff, being out riding and enjoying,” Veeder said. “The other part of it is: It’s already below zero, and you’re feeding cows, and we don’t have water, and a tractor is broken.”

Margo Cilker, center, sings with other performers backstage.

(Bridget Bennett / For The Times)

Decades ago Gene encouraged his daughter to leave the ranch, to see what other possibilities were out there. You have to want to do this, he told her. So, at 16, Jessie began touring locally with her guitar. After high school, she left for a decade: first for college, when she toured the country performing, then for stints living in Minnesota and Montana.

Quietly, Gene hoped his daughter would return, but Jessie wasn’t sure. Lured by the promise of financial security, her friends were leaving for cities such as Minneapolis and Denver.

But an oil boom in 2010 breathed new life into Watford City, and Jessie experienced hope. New opportunities for diverse income streams provided financial stability for newer generations who wanted to return to ranching. She dreamed that her future children would have access to wide open spaces, to care for other living creatures.

The ranch called.

::

In 2017, when Kristin Windbigler became the executive director of the Western Folklife Center, the organization that runs the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering, she had a mission: Attract more young people.

In a way, the gathering mirrored the ranching industry at large: Its performers and attendees were aging, and a new generation did not appear poised to take the reins.

Windbigler, who grew up on a ranch in rural Humboldt County in Northern California, was interested not only in young farmers and ranchers, but also in young people who cared about where their food came from, who cared about the climate, and about the survival of rural Western communities.

“All those things intersect here,” she said of the gathering’s more recent iterations. The vocation of ranching, she said, is about “paying attention,” adding: “It’s about nuance, about understanding the living creatures around you and how you interact with them.”

The Reedy siblings, two of the young people in the spotlight at the festival, appear to understand that nuance. Brigid Reedy, 22, plays the fiddle; Johnny Reedy, 17, the guitar. Inspired by jazz, big band music, blues and a host of folk genres, their music at Elko’s Pioneer Saloon was so bright almost everyone was moving.

Brigid Reedy and brother Johnny Reedy perform at the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering. The Reedys have been coming to the event since they were children.

(Bridget Bennett / For The Times)

Brigid Reedy, left, dances with Tom Morton.

(Bridget Bennett / For The Times)

The Reedys live on their family’s ranch in western Montana and commute 45 minutes to college in Dillon, where Brigid studies horsemanship and English, and Johnny studies English and music at the University of Montana Western. Brigid has traveled the country to perform with her father, who’s been singing and playing the guitar alongside her since she was 2, but what ties everything together for them is the land: the family ranch at the foot of the Tobacco Root Mountains, replete with moose, coyotes, herons, foxes.

When Brigid was a child, the family moved from Colorado to Montana; she and her brother are the first generation in her family to grow up on a ranch. In the past, they lived on cattle ranches and helped neighbors with branding. Today, they primarily run horses.

Brigid Reedy packs up after a performance.

(Bridget Bennett / For The Times)

Brigid evidences a strong sense of place: “We could be doing a song from the ‘20s or something from Ireland or a little mariachi tune, but because it goes through the filter of how we’ve been brought up and our perception of the world, it all becomes, in essence, cowboy music by the time we’re done.”

::

Until recently, Avery Hellman, 30, a folk singer from the eastern Sierra Nevada who performed at the gathering under the name Ismay, lived on their mother’s ranch in rural Petaluma, caring for sheep and restoring creek habitat in areas that had been overgrazed.

Luke Schranz, left, and Alex Monroe dance.

(Bridget Bennett / For The Times)

Tom Morton, left, and Christina Troutman partner up on the dance floor.

(Bridget Bennett / For The Times)

Hellman, who identifies as nonbinary, said that young people “are really struggling” because they want to “have an identity, a tradition to live out.” It’s why Church, the Elko rancher, returned to that life, why Veeder returned. For community and sense of self. To know they belong somewhere.

As with other young people at the gathering, Hellman’s relationship with the ranch is complicated. Nine months ago, they left Petaluma for their own land in the eastern Sierra, where they’ve been focusing on music.

“Being an artist, you need separation from who you grew up with, as in finding your own voice,” Hellman said. Still, they return to their mother’s ranch a couple of days each month to help vaccinate and care for sheep, evidence of Hellman’s deep love and respect for the land.

::

The gathering ended on a Saturday just as it had started — with music and dancing. Jessie and Gene Veeder played one last song together on the big stage in front of a packed auditorium. The Reedys spun together on the dance floor at the Pioneer Saloon.

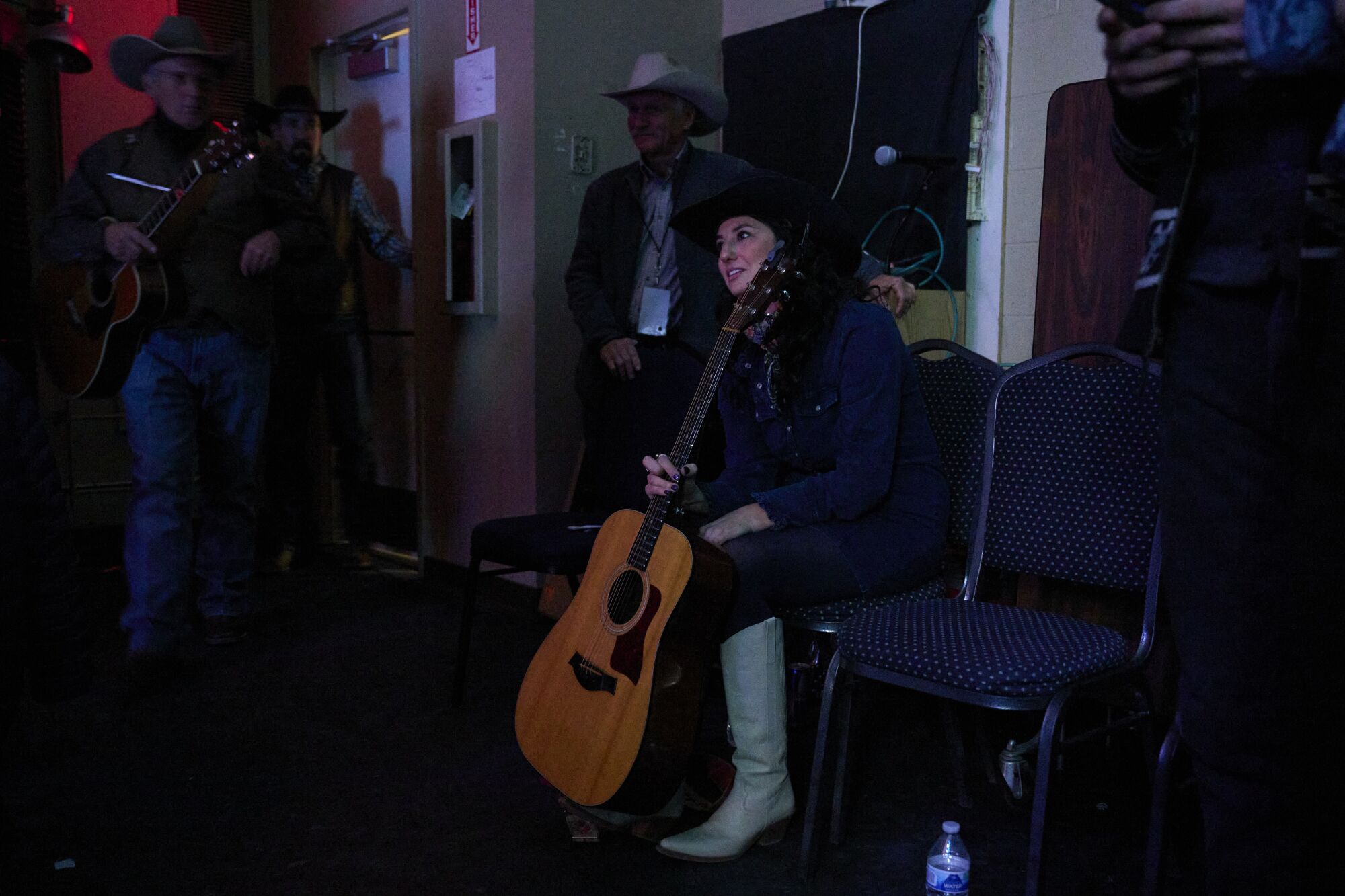

Jessie Veeder, a musician and rancher from North Dakota, waits backstage before her performance.

(Bridget Bennett / For The Times)

In the morning, performers packed up. They drove dozens, hundreds, thousands of miles, east and west and north and south, through winter storms and up icy mountains to North Dakota, Oregon, California, Montana.

The next Monday, Church returned to the Elko gold mine. Back at the ranch, heifers would start calving in a month, and wildflowers would begin to bloom, a rhythm, Church said, that will always be a part of him. Somehow, he added, “we all come home in the end.”