For more than 100 years, films have been made of film. Now, instead of a magazine being loaded on to the camera, a card is inserted that electronically records whatever the camera sees.

Today, most “films” are made electronically. No film is used in the making of them – not the shooting, editing or projection. So they can’t – or shouldn’t – be called films.

A few film-makers, such as Steven Spielberg, still cling to using celluloid, but they are finding it increasingly difficult to find stock. Most of the labs that used to develop and print film have gone out of business. Also, film is an expensive element of a budget; the electronic alternative means you can carry on shooting for virtually no cost.

Those of us who have used film all our lives are able to discern whether or not a film is made on film, but the public has mounted not a whiff of protest.

Some might think I am splitting hairs. After all, not using film has advantages other than cost: the curse of getting a hair in the gate (the rectangular opening at the front of a camera) is gone; the problem of getting dirt on the film swept away. Us old guys who cling to film are dying out; soon, editors will never see a sprocket hole in their lives.

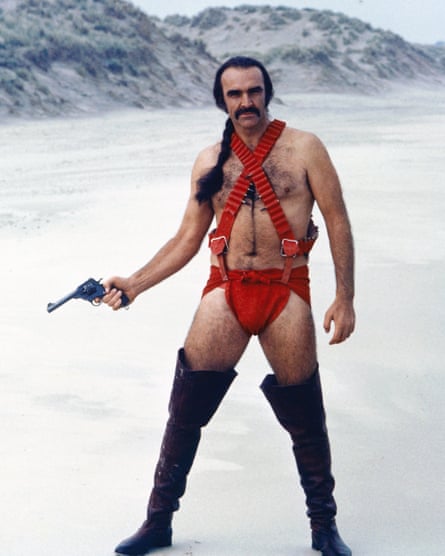

For the finale of my 1974 film Zardoz, I wanted to shoot a scene of Sean Connery and Charlotte Rampling in which they age and die. This involved shooting with a fixed camera, so that we could take them out, age their clothes and faces, put them back in, shoot them a bit more, then take them out and age them further, until eventually they were skeletons that, in turn, crumbled away.

This process took an entire day. Then, the camera assistant unloaded the camera and accidentally exposed the film to the light. This meant we had to spend another whole day shooting it. I also had to restrain Connery from killing the assistant – who soon afterwards changed his name and moved to Los Angeles. I spied him in a cafe in LA one day. “Is Sean in town?” he asked, with a quivering voice.

Film is softer and more human, while electronically made films are harsher and feel more mechanical. The latest iPhones offer not only a “video” option on the camera, but also a “cinematic” one, which Apple claims more resembles old-fashioned film.

Change is inevitable, if regrettable. But there is no reason for language to lag behind. Unless a new picture is actually made of film, it should not be called a film. It should be called a movie.